The House on The Hill: A Spatial

Study of Visitors to the Jackson Sanatorium, 1858-1914

Katherine Berdan

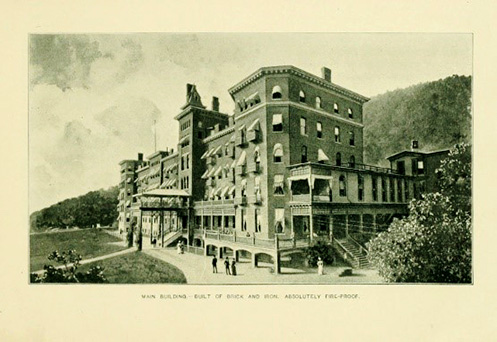

The Jackson Sanatorium in Dansville, New York has a rich and intriguing history that stretches from 1858 to the present day. My research focuses on the years between 1858 and 1914, during the Jackson Sanatorium’s first of two golden ages. The Sanatorium (a name that would only later come to be associated with facilities specializing in mental illness) was purchased in 1858 by Dr. James Caleb Jackson, an active abolitionist and supporter of the early women’s rights movement. He operated the Sanatorium as a health retreat, where patients were treated with hydrotherapy; the use of water for pain relief and medical treatment. My research began purely out of a curiosity of what the structure was used for, but as it continued, it became clear that the Jackson Sanatorium was far more than a local attraction. The Sanatorium was on the cutting edge of hydrotherapy for the late 19th century, and was widely popular. Its holistic approach to medicine and its welcoming atmosphere were hailed nation-wide as “homelike” and not at all like an institutional setting. Guests came from all across the continental United States and even beyond to partake of the healing waters that came from a mountain spring next to the Sanatorium. As a result of these initial findings, I refocused my research on finding out where guests were coming from, and why.

To discover the demographics of the Jackson Sanatorium during its first golden age, I used a variety of sources from the late 1800’s. The Sanatorium published and distributed yearbooks and a quarterly annual journal called Tidings. These primary source journals and yearbooks contain speeches, tips on healthy living, events that occurred, and letters that previous patients wrote to thank and praise the Sanatorium. The journals were composed of mainly social letters, informing others of marriages, births, deaths, and other important events. Some letters were summarized into a few short lines detailing the most recent social news from that “Hillside family member”, as they were referred to, while others were extensive messages detailing the lives of previous patients and their goings-on. Even after their guests had left, it was clear that the Jacksons kept in touch with many of their guests and became very close to them. The yearbooks in particular contained more information about the guests than the journals, as it was the guest’s own writing that was published, instead of being summarized. These yearbooks tended to be complete or partial letters of gratitude or praise for the institution, not just social news.

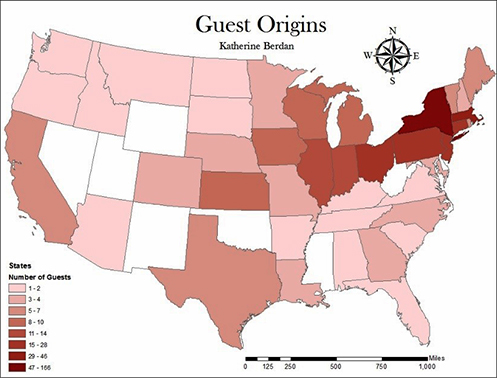

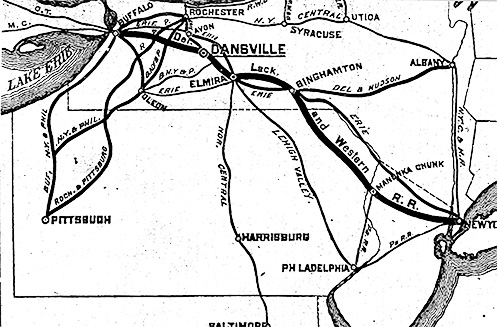

When imported to ArcGIS, the data from the addresses of these letters shows a very wide market area that the Jackson Sanatorium was drawing from. The distribution of locations shows a high percentage of guests travelling from urban areas within New York and its surrounding states. 35% (34.6%) of the 444 addresses located were from New York State alone, and New York City was the most common city listed as a home address. In New York and Connecticut, there were multiple guests travelling from rural locations. However, as the distance between the origin and the Jackson Sanatorium increases, these origins become almost exclusively urban areas. The proximity to newspaper and advertising sources, social gatherings, and railroad stations in cities made it easier for urbanites to hear about and travel to the Sanatorium. The tranquility and beauty of the post-glacial Canaseraga valley where the Sanatorium was located was also an attractive contrast to the busy, dirty confines of a city, which so-called hydropathists believed could be damaging to one’s health. As shown on this map of rail lines in western New York, the presence of direct routes from Buffalo and New York City made the Sanatorium an easy destination for those seeking to escape the hustle and busy of the city to find rest and recuperation. A significant share of the guests were travelling from the Midwest and Central Plains region. However, during the time period that the Jackson Sanatorium was open, other sanatoriums were also attracting a national clientele. For example, Battle Creek Sanitarium in Michigan was a highly popular health resort for Midwesterners. For those who lived far away from Dansville, the proximity of alternative health resort locations may have been a factor. Nonetheless, there were even guests travelling from the west coast; in particular, San Francisco. Of the 444 guest addresses, only 21 were from the Deep South.

Figure 1: The Jackson Sanatorium (Jackson 1890)

Figure 2: Map of concentration of guest origins by state. Created by Katherine Berdan. Data collected from journals and yearbooks containing guest letters and addresses.

Figure 3: Map of train lines leading to Dansville, NY (Yearbook 1899)

Figure 4: The American Costume compared to French fashions for women (The American and French Fashions 1851)

Apart from determining the wide range of locations that the Jackson Sanatorium was drawing guests from, the data also revealed several interesting trends in guest demographics, the first being the presence of visiting reverends and preachers. 42 of the 465 guest entries I recorded (or about 1 out of every 11 people) were reverends who had visited the Sanatorium for personal health, or to give sermons at the chapel. Dr. Jackson approached his practice with a very holistic approach, and focused on the mental and spiritual condition of the body in addition to its physical condition. Church was held every Sunday in the chapel that connected to the main building, and nearly every evening the doctor or a visiting reverend would give a short talk on a variety of nonsectarian topics (The Jackson Health Resort 1916). This holistic approach to medicine clearly drew a religious crowd to the sanatorium, as many of the letters from previous patients mentioned the sermons or the spiritual enlightenment that they found at the House on the Hill. Interestingly, many of the mental and physical exercises, dietary restrictions, and the simplification of daily life practiced at the Sanatorium are similar to that of the yogic lifestyle and spiritual movement that is increasingly popular today. In addition to the yogic lifestyle, the types of hydrotherapy baths used were also similar to cryotherapy methods used today in physical therapy.

While paging through the pamphlets and yearbooks distributed by the Jackson Sanatorium, I also began to record names or titles that appeared to belong to people of political importance or high social status. The clientele of the Jackson Sanatorium were of the middle and upper class, and on occasion, guests of political importance or celebrity status visited the Sanatorium. Among the notable names mentioned by the 1898 and 1899 yearbooks were General John Palmer (a northern Civil War General and Presidential Candidate for the Democratic party in 1896), Baroness Von Hesse, the Duchess of Manchester, General Sampson (A US Navy Admiral), and Pamela Clemens, sister to Mark Twain. Clara Barton was also a patient at the Sanatorium in 1873, and returned in 1876 to buy a house in the village below the Sanatorium (“The Cure”, 1966). She frequently visited the Sanatorium to give lectures and became close friends with the Jacksons. Dansville even became the home of the first Red Cross chapter. Her praise for the Sanatorium strengthened its reputation across the country.

Perhaps the clearest trend in Sanatorium guests is the gender of its visitors. Of the 465 guest entries, I was unfortunately only able to identify the genders of 394 of them. This was due to the lack of gender-indicating first names or titles, as some people were only recorded by their first initials and their last names. Out of these 394 entries, 64% (63.8%) were female, a trend that was not surprising for its time. Medical hygiene and knowledge was sorely lacking by today’s standards. In particular, research in women’s health was neglected or highly inaccurate. A woman’s reproductive system was viewed as a threat to her delicate health, and was often treated as such (Cayleff 1987). Archaic medical procedures like bloodletting were used for everything from morning sickness to puerperal fever. Hygiene was terrible, and infections could easily be transmitted from patient to patient, resulting in high rates of childbed fevers and deaths. After childbirth, middle-class and upper-class women were strongly encouraged to leave motherly duties up to a wet-nurse and rest in bed for upwards of a month (Donegan 1986). During this time period, doctors would prescribe meager meals with little nutrition, closed blinds, and heavy warm blankets to prevent the mother from “catching cold” even in the height of summer. This often led to a deterioration of health, and some fell prone to postpartum depression (Donegan 1986). Hydropathists like Dr. Jackson instead prescribed hearty meals, gentle exercise (or at least a breath of fresh air and sunshine), and plenty of water. The atmosphere at the House on the Hill proved to be especially therapeutic for many women with postpartum depression, because it focused on their physical health, social life, mental state, and spirituality. While postpartum depression was not generally recognized or treated as accurately as today, the symptoms of listlessness, depression, lack of motivation, changing appetites and sleep schedules that were listed by some of the female patients in their letters indicate that this may have been a common issue amongst women of that time. Dr. Jackson’s policy on avoiding caffeine, eating plain but nutritious meals with plenty of vegetables, and getting outside for exercise (Jackson 1907) is something that women today do to combat postpartum depression, in addition to joining support groups, seeking therapy, or taking a break from household duties. An example of Dr. Jackson’s favorite plain, healthy meal to serve in the morning was granula, the world’s first cold breakfast cereal. He developed it himself by baking graham flour, crushing it into pieces, and then baking it once more. He named it granulacerelomia, or granula for short. One of the guests I found in my research was Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, the inventor of corn flakes and the owner of the Battle Creek Sanitarium in Michigan. He later refined Jackson’s method for granula and named it granola (Gilbert 2004).

Dr. Jackson and his fellow doctors on the Sanatorium medical staff were also pioneers of prescribing the use of comfortable, simple clothing without any extra heavy or confining material, like corsets. He found the clothing of that period to be cumbersome, and believed it forced women into a sedentary lifestyle (Donegan 1986). His adopted daughter, Dr. Harriet Austin was the inventor of the American Costume movement, a movement that advocated loose clothing and a knee-length skirt with trousers underneath to allow for easier movement (Gilbert 2004). While it was not exactly the most fashionable outfit for that era, women who visited the Sanatorium and tried the new style rarely went back to their confining dresses and corsetry.

As described in a booklet published by the Sanatorium, the treatment offered there consisted of a “careful regulation of daily life, including diet, exercise, rest and recreation, with cheerful and helpful social and religious influences” (Jackson 1890). The presence of female doctors and assistants and the open-minded and enthusiastic view of women’s rights, lifestyle, and health that all the staff had was a breath of fresh air and is the main contributing factor to the high percentage of female guests. All of the data collected on guest origins, gender, religious association, and daily life at the Sanatorium indicates that it was a highly regarded, nationally known holistic center for health, especially women’s health.

Unfortunately, the popularity of the House on the Hill began to decline in the 20th century. The Sanatorium’s losses and eventual bankruptcy can be tied with a number of factors, including the growing popularity of automobiles in the 1910’s. More and more of the population was purchasing personal vehicles, and with a car, families could go anywhere at any time and no longer had to plan out trips based on their proximity to rail lines. This convenient mode of transportation and the growing popularity of national parks and beach resorts began to divert guests from the Sanatorium to other locations around the country. Places like Saratoga Springs remained popular due to their fame, wealth, and luxurious atmosphere, while new spas and resorts opened up in the west. Despite moving away from the modest lifestyle prescribed by hydropaths by serving rich foods and advocating warm baths (instead of icy cold ones), the Jackson Sanatorium was unable to keep up with the competition. In addition to these factors, medical advances were also contributing to the Sanatorium’s decline. While the high rate of deaths due to poor hygiene or failed treatments had made patients look for other options (such as hydrotherapy) in the early to mid-19th century, the dawn of the 20th brought new advances in science and medicine that helped the populace regain confidence in conventional medicine. Hydrotherapy was fading, and in its place was the beach resort. The Sanatorium had shifted its model from a medically focused institution to a more relaxed atmosphere since its creation and even changed its name to the Jackson Health Resort in 1903 (Health For All 1916), but it couldn’t compete with the growing popularity of new vacation opportunities and the freedom that automobiles provided (Gilbert 2004). In 1914, the Sanatorium filed for bankruptcy and was converted into an army rehabilitation hospital for veterans of World War I (Gilbert 2004). It experienced a revival under the ownership of Bernarr Macfadden as the Physical Culture hotel in 1929 until 1971 before shutting its doors once again. Since then, it has remained empty.

Today, this formerly nationally known institution for health and holistic healing is falling into ruin. Its current owner has made no moves to repair or demolish the building, despite the structural instability that can be seen on the upper levels and severe water damage throughout all levels. Numerous historical buildings in western and upstate New York are in the same situation; too expensive to repair, and too important to the communities they are a part of to be torn down. Whether or not it is possible or economic to preserve these landmarks and monuments physically is a difficult question. However, regardless of what can be done to preserve the site itself, it is just as important to archive and preserve the memory of the influence and importance of institutions like the Jackson Sanatorium.

References

Cayleff, Susan E. 1987. Wash and be healed: the water-cure movement and women’s health. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Civil War Trust. “Civil War Casualties” The Cost of War: Killed, Wounded, Captured and Missing. http://www.civilwar.org/education/civil-war-casualties.html

Donegan, Jane B. 1986. Hydropathic highway to health: women and water-cure in antebellum America. New York: Greenwood Press.

Gilbert, David. 2004. Dansville’s Castle on the Hill: a brief history. Dansville, N.Y.: Dansville Area Historical Society.

Health for All. 1916. Dansville, NY: The Jackson Health Resort.

Jackson, James H, Harriet N Austin, and Walter E Gregory. 1890. The Jackson Sanatorium: the best appointed health institution in America: main building of brick and iron, and absolutely fire-proof. Buffalo, N.Y.: Matthews-Northrup Co.

Jackson, James C, and Harriet N Austin. 1907. What we are trying to do and how we are trying to do it. Rochester, NY: E. R. Andrews.3 Other Volumes, no dates.

“Friends Heard From.” In The Jackson Health Resort Tidings. 1907. Dansville, NY: A.O.Bunnell, 20-32. Total of 5 Volumes; 1905, 1907, 1908

“The American and French Fashions Contrasted.” 1851. The Water-Cure Journal and Herald of Reforms, Devoted to Physiology, Hydropathy, and the Laws of Life.

Volume 12.

“The “Cure” and the Jacksons.” Clara Barton and Dansville; together with supplementary materials, Dansville, N.Y.: [F.A. Owen Pub. Co.], 1966. 36 - 87. Print.

Yearbook of the Jackson Sanatorium. 1898-1899. Dansville, NY: The Jackson Health Resort.

Contributor Biography

Katherine Berdan is an undergraduate student at SUNY Geneseo, where she studies Geography and Environmental Studies. After graduating in the spring of 2016, she plans to continue her research of the American landscape and its preservation.

Return to top