Croghan at Aughwick: History, Maps, and Archaeology Collide in the Search for Fort Shirley

Jonathan A. Burns, Axis Research, Inc.

George John Drobnock, Huntingdon Borough, Huntingdon, PA

Jared M. Smith, Juniata College

Introduction

During the mid-1750s, the mountainous Ridge and Valley section of southern central Pennsylvania was an important theater for colliding European and Native American cultures. The “no-man’s land” of the time, these unsettled forests were located between colonial Philadelphia to the east and the Ohio Country to the west (Wainwright 1959, 69-85). The area that is located in the southeastern part of modern-day Huntingdon County lay along new trade routes through the mountains. In 1753, George Croghan, an Irish immigrant referred to as the “King of the Traders,” made his home in the fertile fields along Aughwick Creek, just north of the modern-day town of Shirleysburg (Volwiler 1926). Aughwick was chosen as a prime location to keep a safe distance from the French at Fort Duquesne, who put a price on his head, as well as the authorities back east, who would arrest him for bankruptcy since his trading activity was interrupted by the start of the Seven Years War (figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of Pennsylvania showing approximate locations of both Fort Shirley and Fort Lyttleton. All images courtesy the authors unless otherwise noted.

It was here that a well-populated settlement, Aughwick Old Town, sprang up adjacent to George Croghan’s homestead and trading post. Because of Croghan’s presence, the location became an important council place between Natives and the provincial government of Pennsylvania. After Major General Edward Braddock’s defeat in the summer of 1755, Croghan fortified his position at Aughwick (then in Cumberland County) at his own expense; this was done in order to protect his stores and the 200 Iroquois that had fled there after George Washington’s defeat at Fort Necessity. Croghan’s fort was strengthened by provincial troops and officially named Fort Shirley early in 1756 by the British under Hugh Mercer. This fort became an important link in the chain of provincial British forts that protected the frontier from the French and their Native American allies. Fort Shirley served as Colonel John Armstrong’s advanced post for the raid on Kittanning in the fall of 1756; and although the expedition was viewed as a success, this garrison was abandoned by Provincial forces later that September (Waddelle and Bomberger 1996, 24).

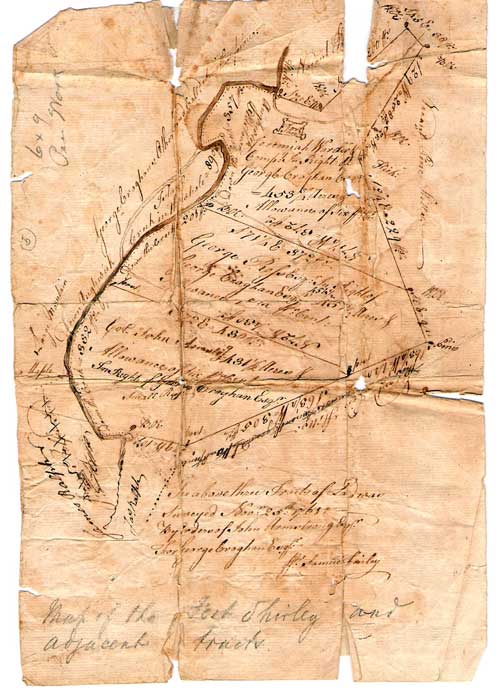

Frequent mention is made of Fort Shirley in historic letters, records, and accounts; however, there is no modern above-ground evidence of the fort. Despite the text on the Pennsylvania State Historical marker located just north of Shirleysburg, the exact location of the palisade fort is unknown. This report assembles and evaluates the historical evidence for the fort’s location in preparation for subsequent archaeological investigations. Our research team explored leads pertaining to the fort at Aughwick in the Pennsylvania Colonial Records, historical accounts, maps, deeds, and aerial photos (figures 2-6).

Figure 2. Early survey map of Croghan’s land conducted by J. S. Africa. Courtesy Africa Engineering Associates Inc., Huntingdon, PA.

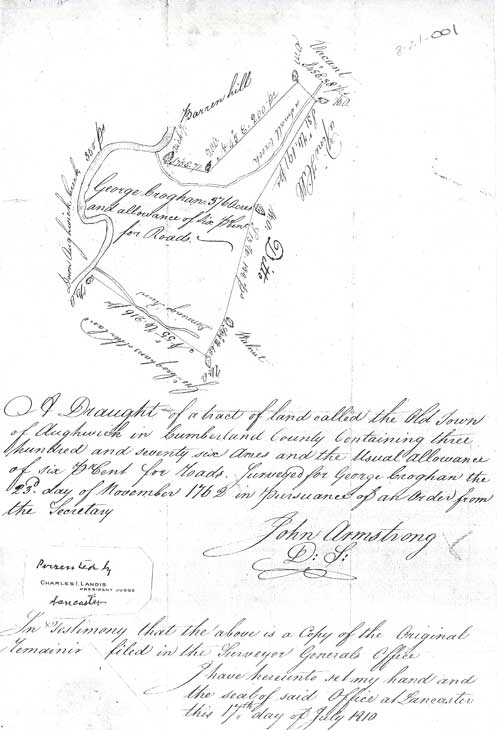

Figure 3. Copy of record of land survey from 1762 of “the Old Town of Aughwick.” Copy produced in 1810. Courtesy Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, PA.

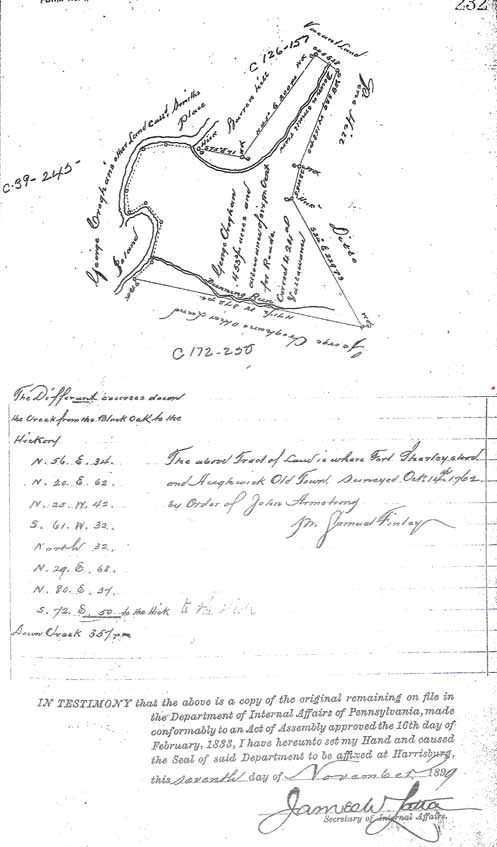

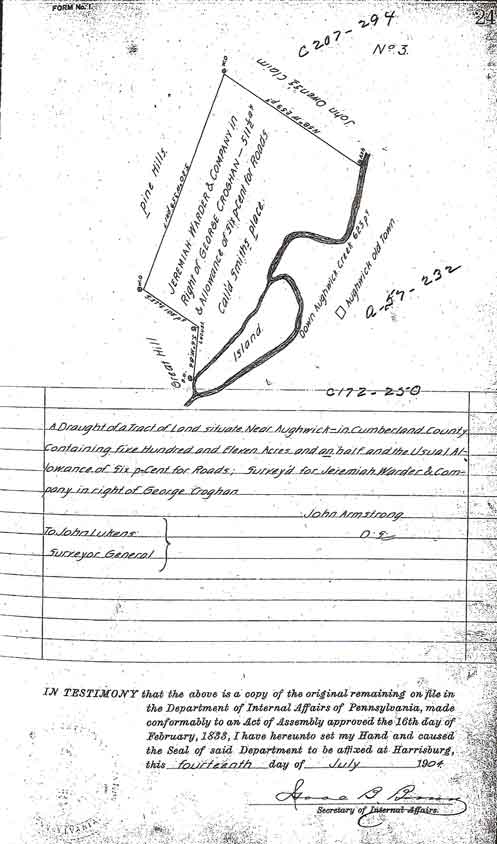

Figure 4. Survey maps of George Groghan’s land. Courtesy the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/ community/land_records/3184/land_warrant_applications/ 387338.

Figure 5. Circa 1762 Warrant map showing location of village of Aughwick, site of Croghan’s Fort, later Fort Shirley. Courtesy the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, http://www.portal.state.pa.us /portal/server.pt/community/land_records /3184/land_warrant_applications/387338.

Figure 6. Aerial photograph of northern Shirleysburg, late 1960s. Courtesy Penn Pilot, http://www.pennpilot.psu.edu/.

Fort Shirley on the Cultural Landscape

Located in Southern Huntingdon County, Aughwick Creek is a tributary of the Juniata River, providing a travel route through the rugged mountains of Pennsylvania’s Ridge and Valley Province. The land north of present-day Shirleysburg occupies prime agricultural ground on the eastern bank of the Aughwick, where the floodplain is wide along the bend in the creek. A small tributary stream, named Fort Run, joins Aughwick Creek at the northern end of a farmed corn field. The story of Fort Shirley cannot be told without elaborating on the life of its “high profile” founder, George Croghan, who likely had his eye on this land as early as 1747 during his expeditions as a trader. He built a house and trading post here in 1753 after moving from the Cumberland Valley of Maryland. Weiser (1916) writes, “This famous valley heretofore referred to as Aughwick, is described as being in the extreme southern part of Huntingdon County, one of a series of valleys through whose entire length ran the celebrated path from Kittanning to Philadelphia, being the great western highway for footmen and packhorses” (573).

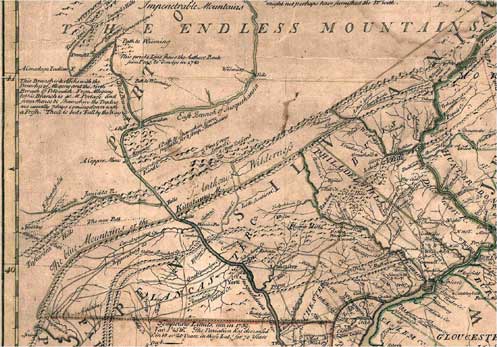

The Evans Map, dated 1749, guided trade and travel from Philadelphia and Lancaster to the central mountains of Pennsylvania (figure 7). Of specific interest is the westward route labeled “new trail” that ends just past Black Log. Croghan’s homestead was off the map to the west. Always pushing the envelope of the western frontier, Croghan states in a letter written to Sir William Johnson dated September 10, 1755, “I Live 30 Miles back of all Inhabitance on ye fronteers…” (Volwiler 1926, 48). By 1755, Croghan was essentially “hiding out” in the back country of the province, since he lost many assets provisioning Braddock’s expedition, in addition to his losses in the Ohio Country during the previous year.

Figure 7. The Evans Map, used to direct traders from Philadelphia and Lancaster to the western frontiers of Pennsylvania. Courtesy Historical Maps of Pennsylvania, http://www.mapsofpa.com.

An early map of south-central Pennsylvania was produced by John Armstrong in 1755, and showed the proposed chain of forts to protect the western frontier (Waddell and Bomberger 1996, 18-19). Darlington’s 1882 map was copied from Armstrong’s map on file at the Public Record Office in London. Croghan was commissioned by the Provincial governor to manage the establishment of this line of forts in 1755, and used his existing fort for the defensive location at Aughwick.

The European concept of lines of forts was no doubt influenced by local topography, in that their presence facilitated the movement of goods and people through travel arteries and provided fortified refuges in times of hostility. A similar situation is documented in colonial Massachusetts, wherein a chain of frontier forts traversed a straight line distance of 38 miles over the rough terrain of the northern Berkshires. Coe (2006) writes, “[a]ll construction in them was timber, with no masonry beyond chimneys and chimney bases, and no earthworks” (5). One of Coe’s archaeological case studies was also called Fort Shirley, by the same namesake. Another similarity lies in the pioneering activities of the local leaders and the speculation of “wild lands.”

Croghan’s Trading Post and Aughwick Oldtown

To reveal the location of Fort Shirley, it is necessary to understand the cultural and geographical significance of the settled land adjacent to the fort. A substantial settlement, Aughwick Old Town, developed around George Croghan’s homestead, a place where Native Americans and whites conducted trade and found refuge. In a letter dated August 16, 1754, Croghan wrote to the governor of the province that the Half King and his fellow Mingo Seneca people had been staying with him at Aughwick since Washington’s defeat (Hazard 1853, 140-41). In a deposition given on August 27, 1754 on file in The British Public Records Office, some Native American allies of Washington informed a Captain John B. W. Shaw that they were going to “Jemmy Arther” for protection. The reference to Jemmy Arther is likely an early reference to the trading post of Jerhemia Wardner, employer of George Croghan. Having no place to go after losing their village at the Forks of the Ohio, the Half King expected his people to be harbored and protected by the provincial government of Pennsylvania. Croghan pleaded to the governor that he could not provide for this many families alone and that he needed funding or compensation.

Conrand Weiser visited Croghan’s homestead at Aughwick on September 3, 1754 to investigate the situation and reported to Governor Hamilton that Croghan had a plentiful bounty of butter, milk, squash, pumpkins, and ample acres of the best Indian corn he had ever seen. Included in the Pennsylvania Colonial Records, Weiser also reported that “…he had encountered about twenty cabins about Croghan’s house, and in them at least 200 Indians, men, women and children…” (149). From announcements regarding runaway slaves near the frontier, we know that Croghan was listed as a contact person for their return. Croghan attracted quite a population with his entourage of partners, employees, servants, slaves, and pack teams, when widespread violence and military actions disrupted his thriving business.

As the political climate was abruptly changing during the time leading up to the French and Indian War, Croghan emerged as a colonial militia leader and the most capable Indian Agent. Croghan scouted for and supplied Braddock’s failed expedition during the summer of 1755; in fact, he and his seven scouts made the first engagement with French forces. Had Braddock accepted the help of the Seneca, Mingo, and Oneida warriors rallied by Croghan, the results may have been much different; however, only seven of the 40 warriors that traveled with him from Aughwick took part in the expedition due to Braddock’s distrust of them. After Braddock’s death and upon returning to his home, Croghan received credible intelligence reports that war parties from Kittanning were planning to attack the frontier from the West. Rather than waiting for provincial funding, Croghan erected a stockade fort at his own expense during the fall of 1755 to protect his stores and the settlement at Aughwick Old Town.

The Fort

A cunning frontiersman, Croghan had no doubt thought out his homestead’s defenses, so when the time came to formally fortify his position during the fall of 1755 he likely incorporated existing buildings into the stockade enclosure. He was quite familiar with the fighting tactics of Native American war parties, and was looked to by the provincial government as an expert on fort construction. In addition to his fort at Aughwick, Croghan laid the plans for and oversaw the beginning of the construction of Fort Lyttleton.

The situation at Aughwick was somewhat different from the erection of military forts, as Croghan’s fort was built after his cabin and store houses, implying that those structures influenced the positioning of the stockade. He is reported to have completed the construction with the help of his men and local labor. Originally referred to as “Croghan’s fort,” it was taken over by provincial forces and renamed “Fort Shirley” in January, 1756. Croghan was commissioned by the Governor as a captain and commanded Fort Shirley for the first three months of 1756 until Captain Mercer assumed command of the garrison of 75 men. In a letter written by Governor Morris to General Shirley, dated February 9, 1756 (and published by in the Pennsylvania Archives in 1853), Hazard writes:

…about twenty miles northward of Fort Lyttelton, at a place called Aughwick, another fort is erected something larger than Fort Lyttelton, which I have taken the liberty of naming Fort Shirley. This stands near the great path used by the Indians and Indians traders, to and from the Ohio, and consequently the easiest way of access for the Indians into the settlements of this Province (569).

The fort remained active as a key outpost until its abandonment was ordered by the governor in 1756. Weiser (1916) writes, “We see thus that Fort Shirley during the times of Braddock’s disastrous venture was an important post to and from which bodies of armed men under Provincial authority were being constantly directed…” (573). Due to its advanced location, Colonel Armstrong and his troops set off from Fort Shirley on August 29, 1756, during the Kittanning Expedition in reprisal for the destruction of Fort Granville. As is written in the minutes of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania, “As Fort Shirley is not easily defended, and their Water may be taken possession of by the Enemy, it running at a Foot of a high bank Eastward of the Fort, and no well Dugg, I am of Opinion, from its remote situation, that it can’t serve the country in the present Circumstances…” (Hazard 32-33).

According to Hunter, “Except that it was a stockade fort and that it was ‘something larger than fort Lyttelton,’ little is definitely known about the structure of this defense” (Hunter 1960, 394). General Forbes described Fort Lyttleton and Fort Louden as measuring 100 feet square; thus providing a minimum size for the stockade of Fort Shirley.

Using Clues from the Historic Record

Court Cases and Deeds

The ownership of the tract where the fort once stood can be tracked by using deeds and surveys available on the PHMC website and other sources. Croghan was the first owner of the land where the fort stood after the area was opened up for settlement. In fact, he is said to have purchased the Aughwick tract from the Onondaga rather than from the Penn family; and therefore, this transaction was a point of contention with the provincial government.

Ownership of Croghan’s land at Aughwick was contested in the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania in a case heard in Huntingdon in 1799. In this case John Armstrong’s sons, James and John Jr., were defending their ownership of the land along with Thomas Duncan against John Morgan, the plaintiff (Supreme Court of Pennsylvania 1871, 529-30).

After a visit to the local survey company, Africa Engineers, Huntingdon, Pennsylvania, we believe that we have found the map of the survey ordered (if not done by) John Armstrong (figure 2), who had a vested personal interest in the property at Aughwick as he owned the deed to one of the three tracts (also redrawn and reprinted in Africa 1883, 342a).

The parcel appears again in the records when the land is deeded to James Fowley in 1773. Rev. Philip Fithian, who was commissioned to survey the Presbyterian churches scattered about Pennsylvania in 1775, wrote about the fort and his stay at the Fowley’s home. Published by the Huntingdon County Historical Society, he writes in his diary: “We crossed Ofwick (Aughwick) Creek and arrived …at Mr. Fowley’s who lives within the walls of old Fort Shirley” (No author 1937, 16). Ownership of the parcel is then transferred to Paul Warner in 1776 and recorded by another survey map.

In 1783, an Irish immigrant named Samuel McCammon came to Shirleysburg from Bucks County and bought the tract that included the fort stockade. This is perhaps the most important account of the change of ownership, as Mr. McCammon is reported to have built his house from the round logs of the old fort house (Jordan 1936, 716). From this, we know that the fort stockade was still visible at this time. It is possible that all the usable wood from the stockade and structures was scavenged for use in the construction of cabins and out buildings, leaving only subsurface features and artifacts to reveal the fort’s location. Any mention or surveys after this period would have been done without visual reference to the stockade.

Written Accounts

There are multiple accounts, from both primary sources and historical interpretations, regarding the location of Fort Shirley; and each of these come along with their own specific complications and contradictions. The first account for the location of Fort Shirley after the Colonial Period appeared in a newspaper called The Standing Stone Banner (published 1853-1855) that was edited by J. Simpson Africa and Samuel G. Whitaker. The Banner’s description appeared in the Pennsylvania Archives (Hazard, 458) during the first attempt to locate the frontier forts of Pennsylvania.

In his history of Huntingdon County, Lytle states:

… (I am) indebted to Samuel McVitty, ESQ., formerly of Shirleysburg, now of Clay Township, this county, with reference to the natural surroundings in its immediate vicinity. The site of the fort has been frequently pointed out to him by those who had seen it, and by Isaac Morgan, who claims to have forted in it in his boyhood days. It was a log fort of considerable strength and size, standing on the edge of the plateau, south of the fort run and west of the road entering Shirleysburg from Mount Union (sic) Aughwick was situated about half-way between the fort and Aughwick Creek, where the depot of the East Broad Top Railroad now stands. Mr. McVitty spent many hours of his youthful hours in gathering arrow-heads, stone tomahawks, beads, and musket balls from this historic ground” (Lytle 1875, 64-65).

Africa writes in his history of Huntingdon County:

The fort stockade was located on the left or south bank of Fort Run, about half-way between the Benjamin Leas house and the farm of Nelson Barton, and a little south of a line drawn between the two. The house of Capt. Croghan, who was in command of the fort, stood a little west or southwest of the fort, near a large pine-tree then, and for three-quarters of a century after, standing near where the station of the East Broad Top Railroad now stands” (Africa 341-342).

A report on the frontier forts was published by Weiser, but according to Waddell and Bomberger it was assembled without critical analysis or organization. However, according to Weiser:

The writer, after an inspection of the site found it on an elevated plot of ground, where now stands the Shirleysburg Female Seminary, within the limits of the borough of Shirleysburg and on the east side of it about one-fourth of a mile from Aughwick. A small stream passes southwest through Germany Valley between the spot where the fort was located and the end of Owing’s Hill, and empties into Aughwick Creek” (567-566).

The reference to an “elevated plot of ground” is unclear, as the seminary location is set back from Fort Run and its confluence with Aughwick Creek. The report also states that the fort supposedly stood opposite a high ledge of rocks used for target practice; however, modern highway construction impacted this hillside so that it cannot be used as a reference.

Another historian, Charles Hannah, presents a photo of the field from 1909, labeling it as the field where Fort Shirley Stood (Hannah 1911, 253). The Huntingdon Borough Sesquicentennial publication from 1938 repeated Lytle’s 1875 description of fort while Samuel McVitty recounts of local elders talking about the fort’s size and recalls collecting military and Indian artifacts in the field as a child thus reinforcing an oral account of the fort’s location.

One of the oldest parcel maps documenting the tract where the fort stood is dated November 23, 1762, and was obtained through the Hamilton Library Collection in Carlisle; unfortunately, the fort location is not indicated. Next we have Surveyor General Armstrong’s survey map of the parcel apparently dated 1761; this, was obtained at the local engineering office and it does show a location for the fort. The map indicates that the parcel that includes the fort was deeded to Jeremiah Warder and Company in right of George Croghan. This map was later redrawn for a plate published by Africa (342a).

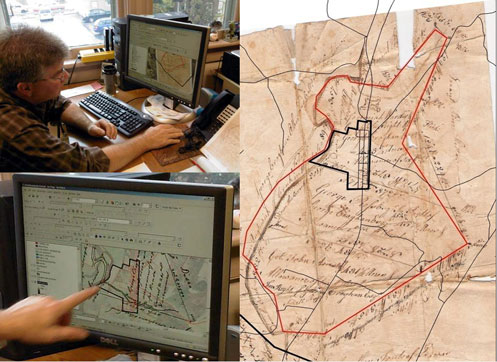

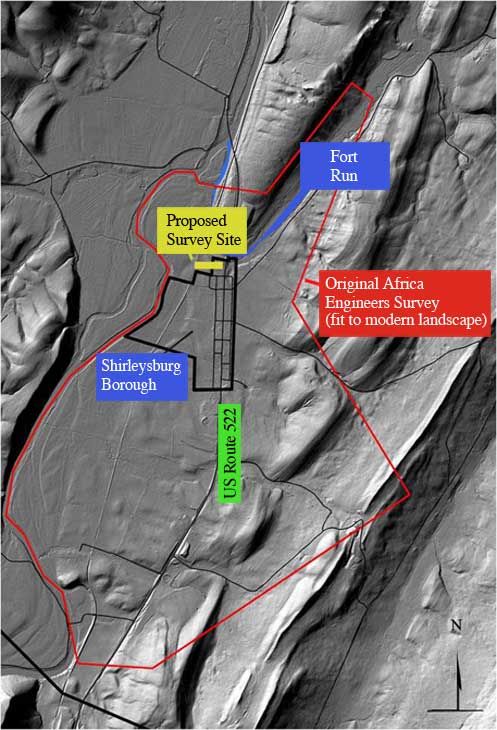

At first glance, the scale and proportions seemed to be relatively accurate when compared to modern aerial photographs and topographic maps of the site. Therefore, we wanted to check to see if the mapped location of the fort could mark the spot. To evaluate the accuracy of the map we went to the Huntingdon County Mapping Office (figure 8) where we had the map overlaid onto the GIS database (figure 9). While fitting the maps, we discovered that the survey from Carlisle was close to 100 perches too short along one of the survey legs (one perch is equivalent to 16.5 feet). This may explain why there is another survey map dated November 25. While it is a more accurate survey map, the date is difficult to decipher, complicating our understanding of the timeline of events surrounding the surveys and court documents. Using distinct features as control points we attempted to match the survey maps to the modern aerial image. We then re-surveyed the three-mile-long tract using the survey notes to reveal that the boundaries match up best nearest along Aughwick Creek, while distortion and inaccuracy occurs along Owing’s Hill and Fort Run. From the GIS, we know that the symbol used to represent the fort measures 600 by 400 feet, which is much too large to have been drawn to scale. Additionally, the overlay places the fort on the steep hill and in the middle of Route 522, so we know that the placement of both the fort and Fort Run are skewed. The GIS is flexible in the different view options; with the redrawn parcel boundary over an areal image shown in Figure 8, and the parcel boundary over a hill-shade surface in Figure 9.

Figure 8. On a visit to the Huntingdon County Mapping office the authors worked with local personnel to overlay maps found in the colonial record onto more recent maps. Courtesy Huntingdon County Mapping Department, Huntingdon, PA.

Figure 9. An outline of the J.S. Africa Map (red) on a modern Shirleysburg (black). Courtesy Huntingdon County Mapping Department, Huntingdon, PA (with assistance from Brian Young, Huntingdon County Mapping Department).

The Need for Archaeology

After reviewing the maps and assembling the written clues, we now need archaeology to confirm or refute the plausible location of Fort Shirley. The presence of a palisade fort and the activities of the troops garrisoned there would produce specific features and distributions of artifacts that should allow the determination of its presence archaeologically. When chosen by Croghan, the location was appealing as a good spot for a homestead rather than defensible ground for a fort. Bearing this in mind, we must consider the fact that the 1750s landscape may have been transformed by geomorphologic processes (for example, by flooding, erosion, and stream channel migration) as well as subsequent farming activity. After visual inspection of various air photo series, there are few (if any) apparent effects on the vegetation coverage from subsurface features. At first glance, we are faced with a seemingly featureless pasture and yard; but by using clues from the written record and historic maps, we have narrowed the search area to the most likely location, that is, south of Fort Run and behind the Leas House.

There are no obvious traces of the fort or any other structures from Croghan’s homestead visible on the aerial photographs of the site. Adding to the complications is the fact that old Route 522 could have impacted the fort and village sites. One way to focus the search for a compound structure such as Fort Shirley is to use geophysical prospecting techniques to detect any traces of subsurface features such as foundations, the palisade wall, and the powder magazine. After narrowing our search using the written record, maps, and GIS; a geophysical survey was started in November with the help of Indiana University of Pennsylvania. A site grid has been established and the test blocks have been staked-out using a laser total station; then, ground-penetrating-radar and resistivity equipment were use to collect data during close interval traverses (0.5 or 1.0 m). The geophysical data will be interpreted further to help guide subsequent archaeological testing.

In lieu of professional archaeological excavations, conventional wisdom suggests that the site is somewhere near the Female Seminary or Leas House. In 1984, a frizen and a .30 caliber lead ball were recovered using a metal detector (approximately 20 ft.) directly behind the Leas house (figure 10). This location is nearer the old railroad station mentioned in the latter accounts of the fort, but further from the mapped location suggested by the Armstrong survey. Military and Native American artifacts are rumored to have been collected from this part of the field over the past 100 years or more; but, these accounts should be substantiated with informant interviews.

Figure 10. A sample of preliminary artifacts uncovered around the presumed site of Fort Shirley.

Conclusions

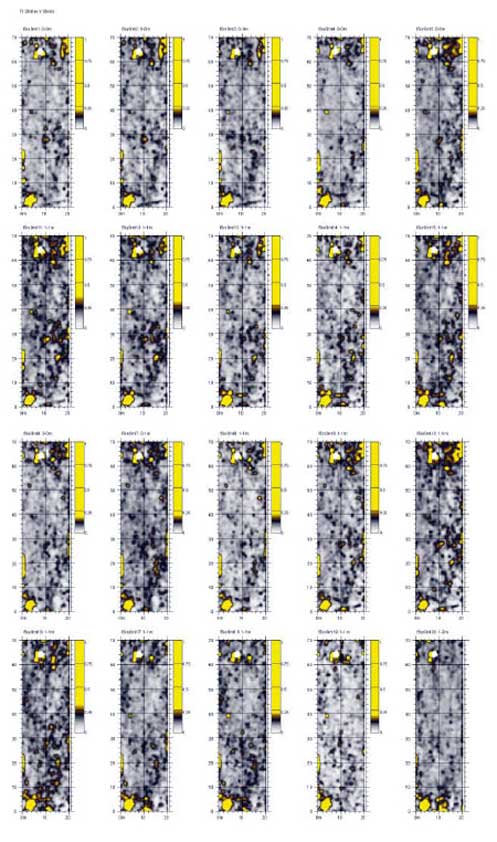

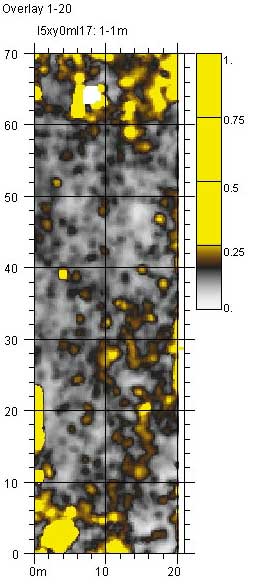

As it fades from recollection and slips into obscurity, it is clear that Fort Shirley’s location north of Shirleysburg will not reveal itself with the passage of time; rather, it is time for informed archaeological testing to confidently locate this colonial-era stockade. From the historic record, we know that important events transpired at Aughwick between 1753 and 1756 related to George Croghan’s presence there. With Aughwick Oldtown factored in, it is evident that the search for Fort Shirley is complicated by the fact that the location was much more than just a military fort. The historic accounts, with all their contradictions and exaggerations, have taken us as far as possible in this search. In cases like this, it takes archaeology to set the written record straight. Fort Run was the obvious reference for the fort’s location on the survey map; however, we have revealed the limitations of the mapping techniques used 250 years ago. To aid in the search for Fort Shirley, a geophysical survey was conducted by Dr. Beverly Chiarulli (Indiana University of Pennsylvania) using a GSSI Sir 3000 Ground Penetrating Radar Unit with a 400MhZ antenna. The location of the survey block, measuring 20 by 70 meters, was based on the historic map and accounts, and the data were collected at 0.5 meter intervals to detect possible fort-related artifacts and features. Although the results are preliminary, potentially meaningful patterning was evident and will help guide archaeological investigations during upcoming summer fieldwork. The data were processed using a computer program (GPR-SLICE) to provide detailed graphic displays of the survey results. In short, variable microwave velocities indicate zones of reflectivity in the subsurface block. The highest reflective zones likely indicate rock concentrations or other features that may have been associated with the fort. Archaeological excavation, however, is needed to explore these potential cultural features. The survey produced 20 incremental slices to a depth of one meter (figure 11). The combination of all 20 slices (figure 12) resulted in a detailed view of the spatial data, making the patterns of subsurface anomalies more visible. Dr. Chiarulli pointed out at least two geometric anomalies of interest in the survey block, which will be explored in future excavation as possible cultural features.

Figure 11. Twenty GPR slices in 4 ns 50% overlapping views. The surface slice is found on the upper left while the deepest slice is on the lower right. Courtesy Dr. Beverly Chiarulli, Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

Figure 12. The combination of all twenty GPR slices collected by Dr. Chiarulli. Courtesy Dr. Beverly Chiarulli, Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

Postscript

Since this article was written, our archaeological testing has discovered the location of one of Fort Shirley’s palisade walls (figure 13). The efforts of the 2010 Pennsylvania State University archaeological field school documented evidence of a long builder’s trench in excess of 95 feet, complete with several charred palisade logs. We will likely return for a second season of fieldwork to find the limits of the fort and to search for interior features during the Summer of 2011.

Figure 13. 2010 Fort Shirley site map showing our GPR survey blocks, archaeological test units, and the projected palisade wall. Courtesy Huntingdon County Mapping Department, Huntingdon, PA.

References Cited

Africa, J. S. 1883. History of Huntingdon County, Pennsylvania. Huntingdon, PA: Huntingdon County Historical Society.

Coe, M. D. 2006. The Line of Forts: Historical archaeology on the colonial frontier of Massachusetts. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.

Hannah, C. A. 1911. The Wilderness Trail. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

Hazard, S. 1853. Pennsylvania Archives. Philadelphia: Joseph Severns and Co.

Hunter W. A. 1960. Forts on the Pennsylvania Frontier, 1753-1758. Harrisburg, PA: The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

Jordan, J. W. 1936. A History of the Juniata River Valley in Three Volumes, vol. III. Harrisburg, PA: National Historical Association.

Lytle, M. S. 1876. History of Huntingdon County, in the state of Pennsylvania: From the earliest times to the centennial anniversary of American independence, July 4, 1876. Lancaster, PA: W. H. Roy Publishers.

No author. 1937. Sesqui-Centennial Celebration of Huntingdon County, Pennsylvania. Hundingdon, PA: Huntingdon County Historical Society.

Supreme Court of Pennsylvania. 1871 [1818]. Armstrong, Armstrong, and Duncan v. Morgan. Reports of Cases Adjudged in the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, Vol. III. Philadelphia: JNO. Campbell.

Volwiler, A. T. 1926. George Croghan and the Westward Movement, 1741-1782. Cleveland: Arthur H. Clarke and Co.

Waddel, L. M. and B. D. Bomberger. 1996. The French and Indian War in Pennsylvania, 1753-1763. Harrisburg, PA: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

Wainwright, N. B. 1959. George Croghan, Wilderness Diplomat. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Weiser, J. G. 1916. The frontier forts in the Cumberland and Juniata Valleys. In T. L. Montgomery, Report of the Commission to Locate the Site of the Frontier Forts of Pennsylvania, Vol. I. Harrisburg, PA: W. S. Ray.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following for their assistance in research: Andy Dudash, Beeghley Library, Juniata College, Huntingdon, Pennsylvania, for access to the Pennsylvania Colonial Records collection; Kirby Lockard, Africa Engineers and Land Surveyors, Inc., Huntingdon, Pennsylvania, providing records used in the J. S. Africa’s History of Huntingdon County 1883; Cara Holtry, “Hamilton Library Collection,” Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle Pennsylvania for assistance to works of Surveyor John Armstrong; Brian Young, Huntingdon County Mapping, Huntingdon County, Huntingdon, Pennsylvania for access to the county digitized aerial photographs and GIS satellite mapping to assembly a map based on eighteenth-century surveys; Kay Coons, Huntingdon County Prothonotary for assistance in locating eighteenth-century court documentation relevant to George Croghan’s land in Shirley Township, Huntingdon County, Pennsylvania; Dr. Beverly Chiarulli of Indiana University of Pennsylvania for access to a GSSI Sir 3000 Ground Penetrating Radar Unit to “slice” the site; and John Wah Axis Research, Inc. and Shippensburg University, Pennsylvania for assistance in Pedology Archaeology relevant to the Fort Shirley site.