Sheet Music as an Indicator of Material Culture (Economics)

A Case Study of the Barr Dry Goods Store in St. Louis, and the Collection of Ida Burrough Coit, Cape Girardeau

Ralph Hartsock, University of North Texas Libraries

Introduction

During the nineteenth century, music printing, like book printing, increased due to the introduction of steam power. Annual sheet-music production rose from 600 titles in the 1820s to 5,000 in the early 1850s (Cornelius 2004, 18-20). Boston publisher Oliver Ditson had an inventory of 33,000 piano pieces; by the 1870s this had increased to 200,000 (Blumhofer 2005, 151).

People of means purchased pianos and other instruments, and collected music (solo piano music, songs for voice and piano). Those buying pianos began using installment credit in 1854 (Lynn 1957, 420). In 1866, Americans purchased 25,000 new pianos at a total cost of $15 million. Production increased each year, and by 1890, 232,000 pianos were manufactured in the United States (No author n.d.[a]). Many hired printers to bind their music together subsequent to their purchases. Some even numbered the pages of the entire “book.” The University of North Texas Libraries, like those of Library of Congress, Eastman School of Music, Indiana University, and others, have collected and accessed these various “binder’s collections” (figure 1).

Figure 1. Binder’s collection, collected by Sarah Carpenter. Courtesy University of North Texas Libraries.

In this paper I will outline the regional influence in southeastern Missouri of the Burrough family. I will describe the component parts of one specific binder’s collection (that of Ida Burrough Coit), a separate collection in St. Louis surveyed for this study, and the companies that advertised on sheet music and other communicative venues. I will also chart the materials advertised and discuss their material-cultural values.

Music and Music Collectors

Although several genres of music are represented in binder’s collections, most are the popular music of the period, fantasies or variations on known opera themes, minstrel songs and tunes, and other dance forms, such as polkas, quadrilles, waltzes, and schottisches. Genteel women learned the basics of piano playing, and practiced and performed these pieces in their homes. It was thought at the time that women could not absorb the abstract content of the higher musical genres, such as sonatas and symphonies, either as composers or performers. Sheet-music production in the United States reached its pinnacle in the 1890s and early decade of the 1900s. At that time, local department stores would hire a pianist, often a young female, to play these popular songs.

Ida Burrough Coit

Jacob H. Burrough (1827–1883), an attorney from Cape Girardeau, Missouri, was on the first board of regents for what is now Southeast Missouri State University. His daughter, Rachel Ida, was born in 1858 (age 12 at the time of the 1870 census), performed at that college’s inauguration, and collected piano music. Her brother, Frank E. Burrough (1865-1903), was a prominent prosecutor in the area in the late nineteenth century.

The genesis of what became Southeast Missouri State University occurred in St. Louis, on October 28, 1873. A board determined that a school should be established in Cape Girardeau, and appointed Jacob Burrough to the executive committee of the Missouri Normal School (Cape Girardeau), the third such college in Missouri. On June 25, 1874, a public program to inaugurate the college was held in Turner’s Hall; this program included music, oration, and the reading of essays (Douglass 1912, 424-25). Following a chorus, an oration by Alex. H. Miller, and an essay by Belle Green came music presented as a duet by Ida Burrough and Mary Ross (figure 2). They sang “In the Starlight,” most likely composed by Stephen Glover around 1860 (Glover 1860a, 1860b). Later in the program was an untitled instrumental duet by Ida Burrough and her sister, Emma (born 1862). A short time later, Ida read an essay on Mary, Queen of Scots. In spring of 1875, Ida Burrough was among the first students to complete the elementary course, a series of classes from various disciplines: geography, composition, vocal music, and philosophy, to name a few.

Figure 2. Ida Burrough Coit, 1880s. Private collection.

Figure 3. A gathering at the Coit house in Denton, Texas. Courtesy Portal of Texas History, University of North Texas, http://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth16130/?q=john%20coit

On February 25, 1886, Ida Burrough married John Clinton Coit (1858-1941), in Denton, Texas (see figure 3). The son of John Taylor Coit (1829-1872), John C. Coit was born December 25, 1858, in Cheraw, South Carolina. In 1859 J.T. Coit left South Carolina for Texas, and settled a 320 acre homestead on what is now the Dallas/Collin County line. John C. Coit attended Austin College in Sherman, Texas, and after his marriage to Ida, spent most of his life in Denton, in banking and real estate (Dallas County Pioneer Association, Stories).

Collections surveyed in the study are the Coit collection at the University of North Texas, and the Supplementary Sheet music collection of Washington University, St. Louis. The Coit collection consists of 42 pieces collected by Ida Burrough Coit. Several pieces, compliments of William Barr Dry Goods Store, St. Louis, included its catalog of nonmusical merchandise on the back cover. Their advertising forms the nucleus of this study of 19th century material culture as communicated on sheet-music covers.

Advertising on Sheet Music

The first perspective one may gain from viewing this sheet music is the relative place in society occupied by Barr Dry Goods Company. William Barr founded his business in 1849 (No author n.d.[b]). They describe themselves as the people “who keep the largest stock and make the lowest prices in the west” (Freeman 1884). The population of the United States during this time was 50,189,209. The center of population was a few miles southwest of Cincinnati, Ohio, in Kentucky (U.S. Census Bureau). The address for the Wm. Barr Dry Goods Co., as listed on several title pages of this music, was Sixth and Olive, to Locust, St. Louis, only blocks from what we know today as Gateway Arch.

As previously noted, the sample for this study includes three scores from the University of North Texas Music Library, and sixteen from the Music Library of Washington University in St. Louis. All music examined was published and sold during the 1870s and 1880s. Some advertisements included patent dates in the mid-1880s. Forty-six different companies are represented in this sample by 242 separate advertisements, most from the textile industry, with others from cosmetics, food, and household items (Table 1).

| Table 1. Industries listed in sampled sheet music. | |

|---|---|

| Textiles: coats, shirts, underwear, corsetry, umbrellas, gloves, silk | 180 |

| Cosmetics: cologne, freckle lotion, soap, dental care, hair restoration | 25 |

| Decorations: lamps, interior | 14 |

| Food, drugs, tonic water | 13 |

| Hardware, dry goods | 10 |

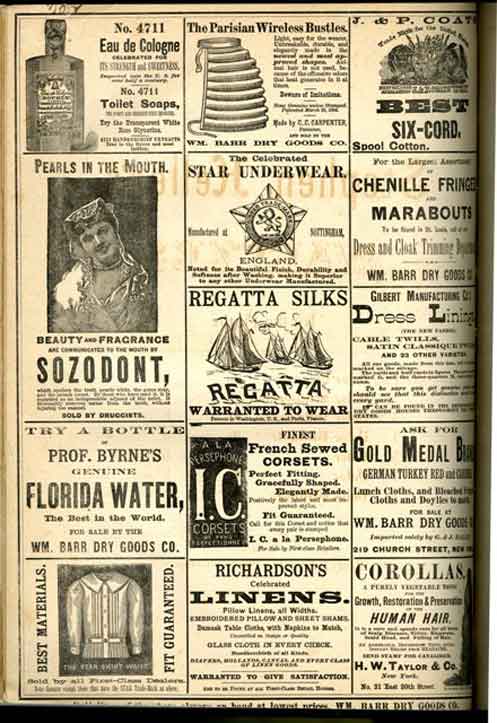

Some of the concerns in the era were similar to those of today – outward appearance, anatomical silhouette, and hair loss. Other advertisements reflect the weather of the region and time, with a definite winter season occurring annually. In one title, Enoch Morgan had an entire page of narrations, similar to a comic strip, all to sell their soap product, Sapolo. The top six specific advertisers were: Star shirts, J&P Coats, silks from Briggs & Company, interior decorations from Arabesque Hollands, linens from Gilbert, and underwear from Star (Tables 2-3).

| Table 2.Advertisements in sampled sheet music. . | |

|---|---|

| Star shirts | 14 |

| J & P Coats | 13 |

| Briggs & Co., New York, silks | 11 |

| Arabesque Hollands, interior decoration | 10 |

| Gilbert Cut Linen, patterns | 10 |

| Star underwear | 10 |

| Table 3. Types of textiles represented in Table 2. | |

|---|---|

| General Textiles | 78 |

| Textiles, silk | 35 |

| Textiles, underwear, corsetry | 33 |

| Textiles, shirts | 15 |

| Textiles, coats | 13 |

| Textiles, other: gloves, umbrella, quilts | 6 |

Parallels to material culture of today can be seen, particularly in the cosmetics (figure 4). Sozodont renders teeth pearly white. H.W. Taylor uses pure vegetable oil for hair restoration. Professor Byrne sold genuine Florida water. There was also a sense of self-sufficiency required for living on the frontier. Thus, Gilbert Manufacturing Company sold patterns that could be sewn by those living in what was called “the west.”

Figure 4. Malley, W. E. 1870. Under the Elms: Waltz. St. Louis: Wm. Barr Dry Goods Co. Courtesy University of North Texas Libraries.

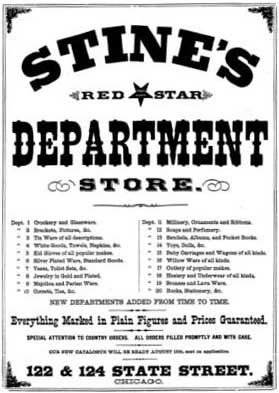

Barr was not alone is this method of advertising (figure 5). Stine’s Department Store in Chicago issued a store directory on the back page of their Dime Series Popular Music (Wrighton 1878).

Figure 5. Wrighton, W. T. 1878. Her Bright Smile Haunts Me Still. Chicago: Wyman & Davis; Stine’s Red Star Department Store.

Conclusion

A large amount of knowledge about material culture may be gleaned from artifacts of artistic expression: music, film, paintings, sculpture. Two of my colleagues have shown how much research can be performed on our cultural heritage. Garth Tardy of the University of Missouri, Kansas City, has cataloged music, with colorful pictorial art on the title pages and sheet music covers. These include animals, landscapes, artifacts (such as clothing), and various other concepts (extra-terrestrials, war, nature) (Tardy 2009). Patrick Loughney, formerly the head of the Moving Image Section of the Library of Congress, and now chief of the Library’s Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation in Culpeper, Virginia, noted that early films of Thomas Edison are being examined not only by film enthusiasts, but by scholars in various disciplines – sociology and history (Museum of Modern Art, Library of Congress 2005). Like the sheet music and printed materials of the time, the films present a record of culture during the early 20th century, such as lifestyles, attires, buildings that no longer exist, and technology used at the time, such as horse-drawn fire engines. There is room for more research into American culture of the late nineteenth and early 20th centuries through its music, art, and media materials.

References

Blumhofer, E. L. 2005. Her Heart Can See: The Life and Hymns of Fanny J. Crosby. Grand Rapids, MI: W. B. Eerdmans.

Cornelius, S. H. 2004. Music of the Civil War Era. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Dallas County Pioneer Association. n.d. “Stories of the Pioneers. Coit, Henry William.” http://www.dallaspioneer.org/stories/pioneers.php, http://www.dallaspioneer.org/stories/pioneers.php?ID=255, accessed October 9, 2009.

Douglass, R. S. 1912. History of Southeast Missouri, volume 1. Chicago: Lewis Publishing Company.

Glover, S. 1860a. In the Starlight: Duet. Boston: Oliver Ditson.

_______. 1860b. In the Starlight: Duett. Brooklyn: D.S. Holmes.

Lynn, R. A. 1957. “Installment Credit Before 1870.” The Business History Review 31 (Winter): 414-424.

Museum of Modern Art, Library of Congress. 2005. Edison: The Invention of the Movies. DVD. Produced by Bret Wood. New York, NY : Kino on Video.

No author. n.d.[a]. “Marketing History of the Piano.” http://www.cantos.org/Piano/History/marketing.html, last accessed May 28, 2008.

_______. n.d.[b]. “History of St. Louis Neighborhoods: Downtown (C.B.D.)” http://stlouis.missouri.org/neighborhoods/history/cbd/index7.htm, last accessed October 31, 2007.

Tardy, G. 2009. “More Than a Melody: Providing Graphical Subject Access to Sheet Music.” Poster Session, Music Library Association, Chicago, IL, February 20, 2009.

U.S. Census Bureau. “Mean Center of Population for the United States: 1790 to 2000.” http://www.census.gov/geo/www/cenpop/meanctr.pdf, last accessed January 14, 2010.

Wrighton, W. T. 1878. Her Bright Smile Haunts Me Still. Chicago: Wyman & Davis; Stine’s Red Star Department Store. American Memory, Library of Congress. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/sm1878.07871 last accessed October 13, 2009.

Music Referenced

From University of North Texas

Freeman, J. J. 1884. Falka Lancers. New York: R.A. Saalfield.

Malley, W. E. 1870. Under the Elms: Waltz. St. Louis: Wm. Barr Dry Goods Co.

Strauss, J. 1870. Roses from the South, op. 388. St. Louis: Wm. Barr Dry Goods Co.

From Washington University

Adams, S. 1880? Nancy Lee. St. Louis: Wm. Barr Dry Goods Co.

Costa, M. 1880? March from Naaman. St. Louis: Wm. Barr Dry Goods Co.

Egghard, Jules. 1882. Blue Bells of Scotland. New York: R.A. Saalfield.

Fahrbach, P. 1885? Tout a la Joie: Galop. St. Louis: Wm. Barr Dry Goods Co.

Hadden, F. W. 1883. Hurricane Galop. New York: R.A. Saalfield. St. Louis: Wm. Barr Dry Goods Co.

Hitz, F. 1880? In Mid-Summer: Aubade, op. 276. St. Louis: Wm. Barr Dry Goods Co.

Jungmann, A. 1880? Loving Memories. St. Louis: Wm. Barr Dry Goods Co.

Pfeiffer, J. 1883. Du bist wie eine Blume: Op. 17. New York: R.A. Saalfield.

Sainton-Dolby, C. H. 1880? The Cottage on the Moorland. New York: R.A. Saalfield.

Schroeder, H. 1880? Lord, Be with Me in My Walks: Beautiful Sacred Solo. St. Louis: Wm. Barr Dry Goods Co.

Skelley, J. P. 1883. Peck’s Bad Boy. New York: R.A. Saalfield.

Snow, F. H. 1880? Oscar Wilde Galop. St. Louis: Wm. Barr Dry Goods Co.

Sullivan, A. S. 1880? Golden Days: Ballad. St. Louis: Wm. Barr Dry Goods Co.

Sullivan, A. S. 1880? Patience: Waltz. St. Louis: Wm. Barr Dry Goods Co.

Wagner, R. 1885? Pilgrim Chorus: Tannhauser. St. Louis: Wm. Barr Dry Goods Co.