Manayunk; A Place of Waterpower, Textile Industry, Gentrification, and “Hollywood”

Wayne Brew, Assistant Professor of Geography

Several of the images in this article are multi-part, and are presented here as slideshows. If any of these is no longer looping by the time you encounter them, select the Play button to restart them.

Introduction

The first place that comes to mind for many in relation to water power and textiles is New England, but a similar story can be told for Manayunk, a section of Philadelphia located along the Schuylkill River. In 1819 the Schuylkill Navigation Company completed a 2 mile section of canal to provide better transportation to the anthracite coal fields to the north. This triggered the development of textile mills along the canal to take advantage of the available water power. By the mid-nineteenth century steam engines replaced water as the power source. Manayunk continued to thrive as an industrial area until the mid-twentieth century attracting many diverse groups of migrants. This illustrated paper will provide a brief history of transportation, industry, and demographics of Manayunk. Gentrification, the business revitalization of ‘Main Street,’ adaptive reuse, contested space, boundaries and Hollywood films shot in this neighborhood will also be discussed.

Physical Setting and a Brief History

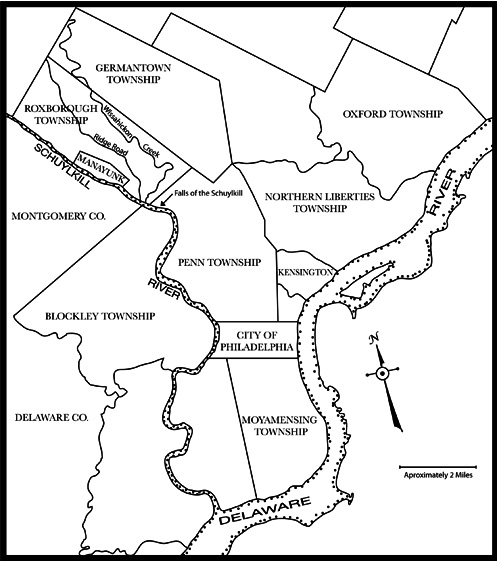

Roxborough was one of the original townships created by William Penn. Philadelphia County is roughly shaped as a ‘Y’ with Roxborough located in the left upper limb, northwest of the original city set out by Penn (see Figure 1). Philadelphia is located on the ‘Fall Line,’ the point of transition between the relatively flat coastal plain with navigable rivers and the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. A steep ridge is created by the Schuylkill River and Wissahickon Creek is located here. A well-used Native American trail that starts near the Delaware River and goes in a northwest direction climbs this ridge. Soon after European settlement this trail becomes a turnpike which is now called Ridge Avenue. The top of the ridge was dominated by farms. Grist mills and access roads were soon established along a steep sided ravine carved by the Wissahickon Creek which runs parallel to the old turnpike route and the Schuylkill River.

Figure 1 shows the location of Manayunk in relation to the original townships (and city) in Philadelphia County. Manayunk was originally a subsection of Roxborough Township and became its own entity in 1840 after the rapid development of textile mills. All of Philadelphia County becomes the city of Philadelphia in 1854. Figure 1 is adapted from a figure in Cynthia Shelton’s book “The Mills of Manayunk” by Catherine Brew.

The Schuylkill Navigation Company was established in 1815 (Shank 1960) to improve navigation along the river in order to tap into the agricultural and natural resources (anthracite coal) of the interior. By 1819 a 2 mile section of canal (Figure 2) was completed in Roxborough Township which triggered the development of textile mills along the banks of the river using the available water power to run the looms. This area, first known as Flat Rock, quickly saw the development of more mills, which attracted skilled, and predominantly Protestant, English and Scotch-Irish migrants (Shelton 1986). The town was named for the Native American term used for this area, Manayunk, and was carved out of Roxborough Township in 1840 (Fisher 2006). Manayunk and Roxborough eventually were incorporated into Philadelphia in 1854.

Figure 2 shows several views of the canal and towpath as it exists today in Manayunk. The canal created water power for the development of textile mills along it. The original mills have been torn down and are now used mostly as parking (2a). Other industrial buildings have been turned into loft-style living (2b). One of the remaining buildings has a mural depicting the canal era (2c). All photographs in this article are by the author.

By 1850 steam engines replaced water as the power source for the looms and mills are established away from the canal, throughout Manayunk. Boom periods (for example, the Civil War) and bust periods (early 1890s depression) followed in the textile industry. The first Catholic migrants were from Ireland, but by 1890 the new migrants to Manayunk were from Eastern (mostly Polish) and Southern (mostly Italian) Europe, with each group establishing their own parishes. These parishes exist to this day and in some cases are within sight of each other. A thriving business district was established along ‘Main Street’ to serve this section of the city. It would not be accurate to call Manayunk the ‘Lowell of Pennsylvania’, but it was sometimes referred to the ‘Manchester of America’ (Shelton 1986). For a more in-depth history of the mills and associated labor issues please see Cynthia Shelton’s informative book “The Mills of Manayunk.” | Return to top

Transportation

In the early 1830s, soon after the completion of the canal, a railroad connecting Manayunk to Philadelphia and Reading was completed (Shelton 1986). This eventually became incorporated into the Reading Railroad and the tracks ran at street level parallel to Main Street on Cresson Street. The railroad was elevated through Manayunk in the 1920s (Figure 3). One of the more interesting remnants of this line is the Shawmont Station (no longer a stop) to the north of Manayunk. The station was built in 1834 and is considered as the oldest railroad station still standing in the United States. An image of the station is provided on the following web site (last checked in June 2011):

http://politicalaction.com/philanet/Philadelphia/railroads/

Shawmont_Train_Station.html

Figure 3 shows the Reading Rail as it exists today. The tracks once ran at street level, but were elevated in the 1920s. The tracks are now used by the Southeast Pennsylvania Transit Authority (SEPTA) as a commuter line that connects Manayunk to Center City Philadelphia and Norristown. A picture of Cresson Street (and other then and now photographs) can be found in the website link (last checked in June 2011): http://wbdocu.blogspot.com/2009/01/manayunk-rephotographed_27.html.

It was not until the 1880s when the Pennsylvania Railroad muscled its way into Manayunk, crossing the river from the west side on a utilitarian iron’s bridge. The line then ran parallel to the Reading Line north to Norristown. The Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) replaced the iron’s bridge with a concrete arched bridge in 1918 which has subsequently become the main symbol and a landmark for Manayunk. When the Southeaster Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) took over the PRR operations it shut down the stations and stops north of Manayunk. The concrete arched bridge was taken out of service and much of the PRR right-away was converted to a bike path that connects Philadelphia to Valley Forge, with plans for eventual connections to Reading. There are also plans to use the bridge and right-away to connect the bike path with the communities across the river.

Figure 4 is the arch bridge as seen today. This bridge replaced the original’s bridge in 1918. SEPTA no longer uses the bridge and plans are underway to use it as a bike and hiking trail connecting the suburbs to the existing bike trail that runs from Manayunk to Valley Forge. A web site with an amazing set of photographs from a post card collection is linked below which shows the original’s bridge (last checked in June, 2011): http://maggieblanck.com/Land/Philly.html.

The canal continued to operate (although much diminished) until 1926 and was used almost exclusively to haul coal from the anthracite region. The remnants of the canal can still be seen in Manayunk (see Figure 5). The ruins of a two tier or double lock system remain at the south end and a two way lock and dam (Flatrock Dam) and the ruins of the lock tender’s house are at the north end. The canal fell into disrepair until it was refurbished in 1979 (Sanders 2002). The towpath is used by hikers, runners, and bicyclists and is part of a larger system of bike paths that have been established in the Philadelphia region. There have been plans to refurbish the locks and connect the canal back to the river, but currently lacks funding to complete.

Figure 5. Figure 5a is the canal just above the remnants of a two-tier lock system. The tow-path runs approximately 2 miles to the next lock system and the Flat Rock Dam. It is used by joggers, strollers and bicyclists (5b). The tow-path and canal were refurbished in 1979 and have been maintained in good condition since.

What’s in a Name?

The name Manayunk was derived from a Lenape Indian term for this location along the river that meant ‘place where we drink’ (Sanders 2002), which made sense then and continues to make sense now for different reasons (see below). The canal created a sliver of land between itself and river which came to be known as Venice Island and was home to textile mills and other industries. Manayunk was such a prominent place that a rail stop on the other side of the river was called West Manayunk, which gave the name to the community that grew there outside the city limits of Philadelphia. When Manayunk fell on hard times and most of the business district and mills shut down, ‘West Manayunk’ was renamed in the early 1950s to ‘Belmont Hills’, the vote winner by a large margin of the residents. Since Belmont means beautiful hill in Italian it can be literally translated to the redundant beautiful hill hills; just don’t call it Manayunk! The details behind the name change makes for an interesting story that implicates James Michener and Albert Barnes. You can find the details through this link (last checked in June 2011):

http://www.mainlinetoday.com/core/pagetools.php?pageid=

6022&url=%2FMain-Line-Today%2FApril-2007%2FFRONTLINE-Retrospect%2F&mode=print

More Recent History and a Personal Account

By the 1960s the Main Street business district was largely abandoned and the residents needed to go to nearby auto friendly shopping centers located on City Line Avenue and Ridge Avenue to buy necessities. Only a few industries were still operating; a frozen fish processing plant (Mrs. Paul’s), a soap factory, a handful of textile mills, and two paper mills. While the industries were gone the residents were not. The narrow streets crowded with two story worker houses that hugged the steep hills were still occupied. This is the Manayunk that I moved to in 1983. | Return to top

Figure 6 shows the last of the building supply companies that continue to operate on Main Street. When the business district started declining the reasonable rents or building costs attracted these uses. This company took over a former theater called the ‘Empress’.

My move to Manayunk was a practical and aesthetic decision. I was a graduate student at Temple University working summers in a paper mill in Manayunk, and did not have a car. My 8 mile commute to work from the lower northeast side (Kensington) of the city could take up to two hours by bus. The cheap rent, interesting architecture, canal ruins, steep vistas, and ten minute walk to work made it a practical and very interesting place to call home. I called it ‘The Poor Man’s San Francisco’ because of the steep hills. I started a new job in the suburbs and moved out of Manayunk in 1986 to nearby Roxborough, lured by parking and stores within walking distance. I witnessed the transformation of this neighborhood perched on the hill above, similar to the mill owners who built their homes at the crest of the hill to keep an eye on their factories and workers below.

While Manayunk’s fortunes were declining it was the goal of many to move ‘up’ the hill to Roxborough or to the suburbs. It is interesting how boundaries change with economic prosperity, trendiness, and perception. For local realtors the boundaries of Manayunk shrunk until about 20 years ago when Manayunk became a hip and happening place. Now many houses listed well outside the official boundaries are now listed in Manayunk. So in my case I bought my house in Roxborough in 1986 and sold it in Manayunk in 2003.

Gentrification

It was common knowledge while I was living in Manayunk that something was going to happen, but it did not happen quickly. There were weak signals that changes were underway in the 1970s, a few antique stores had opened and closed (Fisher 2006), but not much else that would indicate a major change was coming. Until the mid-1980s Main Street was still dominated by vacant business, building supply firms (see Figure 6), and a handful of surviving bars and sandwich shops that catered to local residents.

It is interesting to look at places that have been gentrified to identify the driving forces behind the revitalization; is it government policy, urban pioneers, or business driven? All three factors can be found in Manayunk, but I think the primary driving force was business. Although the canal was refurbished in 1979 (Sanders 2002) and Main Street was designated as a historic district in 1984 (Fisher, 2006) it is not clear how much immediate effect this had on revitalization efforts. The biggest early investor in Manayunk real estate (and still a major landowner) claimed in an interview that he did not even know that the area had been designated as historic and it had no influence on his decisions to purchase the buildings (Fisher, 2006). Whether you argue whether it was government or business that led to the revitalization of Main Street, the residential areas were still occupied by long-time residents who owned their houses. The business district may have been mostly abandoned, but the residential areas were not. When I lived in Manayunk my immediate neighbors were predominantly long-time residents. There was no significant influx of artists or other ‘urban pioneers’ until much later in the process.

Figure 7 (a through e) shows several views of the Italianate and Queen Anne architecture along Main Street. These structures have a turn of the century charm that many find desirable. In most cases no drastic changes needed to be made for adaptive reuse since they were constructed for business purposes to begin with. Most of the structures had not been altered (modernized) because of the rapid decline of the business district.

There are several factors that made Manayunk attractive to developers and potential business operators; namely aesthetics (adaptive re-use), accessibility, and cost. The buildings on and near Main Street are turn of the century Italianate and Queen Anne styles, constructed of brick and local stone, and for the most part unaltered. The changing whims of taste did not get a chance to alter the integrity of the buildings; they were like a time capsule of the past. Along with the architectural charm was an urban landscape built on a human scale of 2 to 3 stories that already had a history of businesses at the street level with apartments above. Figure 7 shows several views of the architecture along Main Street. Manayunk has direct connections to many areas by rail and highway. The Schuylkill Expressway is one of the main arteries (albeit a bit clogged much of the time) in Philadelphia that has an on/off ramp just across the river from Manayunk. Along with accessibility Manayunk is closer to affluent suburbs (Main Line Communities) than center city Philadelphia. This provides a near-by upscale clientele. Real estate values for Manayunk had fallen and remained fairly low until well into the early1990s. Neil Smith (Smith, 1996) applied the term “rent gap” to describe this situation as the difference in the price of the building (low) compared to its potential worth at a later time (high). As Manayunk became a more popular destination rents went up, but the initial low prices helped attract many new businesses and investors in the early phase of the revitalization process.

With these amenities it was high-end restaurants that led the way with one of the early originals (1987) still there; Jakes (see Figure 8). I would like to think that Jake’s eclectic façade was influenced by relatively long term denizens (1980) of Main Street, the architects Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown (‘Learning from Las Vegas’). Other businesses followed including clothing boutiques, gift shops, hair salons, art dealers, and bars. When the rents increased some of the small businesses could no longer afford the rents. Several chain businesses moved in including The Gap, Bed Bath and Beyond, Banana Republic, and Chico’s. Interestingly many of the chains-stores are now gone; Pottery Barn, Restoration Hardware, and the ubiquitous Starbucks survive. Main Street cannot provide the foot traffic of a shopping mall during normal business hours; plenty of foot traffic can now be found between 10 PM to 3 AM, but many are not looking for furniture, housewares, or clothing!

During period of most of the business district change, the character of the residential district changed little. House prices remained reasonable, many long-time residents remained and turnover was low. Residents did not like the changes taking place and had a long list of grievances including; parking issues, late-night noise, a frat house atmosphere, public drunkenness and urination. This conflict was often between the long-term residents and the younger crowd that was frequenting the many bars and restaurants. | Return to top

Figure 8. The first upscale restaurant on Main Street was ‘Jaimies’ (1986) which served French Cuisine and was closed by the early 90s. The photo shows ‘Jakes’ which opened in 1987 incorporating an electric menu and façade. Jakes is still open and has recently opened a wine bar and small plate bistro next store called ‘Coopers’.

As the turn of the century approached the number of long-time residents was declining and newer residents were moving in. The U.S. Census statistics for owner occupied housing reflect the change. In 1980 75% of the homes were owner-occupied. In 1990 this fell to 64%. In the core area of Manayunk (Philadelphia Census Tract 214) owner-occupied houses was down to 52% by 2000. The 2010 census data is not available at the time this article was completed, but the 2005-2009 American Community Survey reports an estimated drop of the owner-occupied houses to 45.7%. The change shows long-term residents being replaced by renters. The escalating price of homes have attracted outside investors who have bought properties and converted them to rentals. Another significant driver of change was government policy; a ten year tax abatement for new or significantly remodeled (loft apartments in old industrial buildings) structures. The long-term residents and any interested ‘pioneers’ could not compete with outside investors and their resources. Housing prices escalated significantly up until the 2008 housing bubble.

Yunkers and Yuppies

Temple University Professor Ricki Sanders wrote an article (Sanders 2002) that captured the social conflict between the long-time residents of Manayunk (some who proudly call themselves Yunkers) and the new residents moving in (Yuppies). This change was slow at first, but by the time Professor Sanders was interviewing residents for the article it was changing rapidly and you can feel the resentment in their statements. A part of this conflict can be seen in the landscape. Figure 9 shows two bars in Manayunk that are just around the corner from each other. The Cresson Inn has a sign that states “Where Real Yunkers Drink” and is the last of the original, pre-gentrification bars left in the business district of Manayunk. YUNKERS is a recent addition that is not for locals, but wants attract the hip young college students visiting Manayunk. ‘The place we go to drink’ indeed! My favorite bar in the old Manayunk was called the 3rd Base (the place we go to drink before we go ‘home’) where a bartender with a gravelly Tom Waits-like voice named Wayne held court while serving up cheap drafts of beer.

Figure 9 is two different bars in the Manayunk business district. The Cresson Inn (9a) was operating before gentrification and you see on their sign the cliental they cater to. Yunkers (9b) was opened recently catering to different crowd that now live in the neighborhood.

Jacobs, Lynch, Bike Races, and Hollywood (Oh My)

In 1997 the Philadelphia city council put a five-year moratorium on any new liquor licenses in Manayunk which was used to effectively stop any new restaurants from opening on Main Street (Fisher 2006). The fear was that it would affect the economic health of the business district if every business was a restaurant. Many felt that this was a cynical attempt to stifle competition with established restaurants occupying properties owned by the largest land-owner (Fisher 2006). Cynical or not, this relates well to the ideas put forth by Jane Jacobs in her book “The Death and Life of Great American Cities” where she argued that a diversity of uses is essential to the vitality of urban neighborhoods. This action has appeared to work and slow down the opening of restaurants and bars, but these businesses still dominate and rely on customers coming from elsewhere. | Return to top

Figure 10 is several photos that show the ubiquitous nature and connection of the landmark bridge to Manayunk. The bridge as ‘gateway’ to Manayunk (10a) closed off for a recent bicycle race. A view of the bridge crossing the canal (10b) with a close-up of the end of the aesthetic maintenance (10c). The bridge incorporated into business signs (10 d and e), a high-rise apartment building (10f), and even an ice sculpture (10g) at a recent event.

Many of Kevin Lynch’s concepts about place could be applied to Manayunk. I have already briefly discussed edges (boundaries) and districts, but the one that stands out the most is the concept of landmarks, which are objects that are easily identified and which serve as well-known reference points (Lynch 1960). The readily identifiable landmark is the concrete arch bridge built by the Pennsylvania Railroad that prominently crosses the Schuylkill River at considerable height (to maintain the level right-away) over and into Manayunk. Not only is this a well-known reference, but where the bridge crosses Main Street it acts as an arched gateway into Manayunk, which according to Lynch, “strengthens a landmark” (Lynch 1960, 81). Many think that this bridge is very old, but it was built to replace a more utilitarian steel girder’s bridge in 1918. Manayunk hosts an art festival every year and a poster is commissioned. It is rare when the poster does not reference the arched bridge in some way. Figure 10 is a collage of photos that indicate the ubiquitous nature of this landmark. Large sums of money have been spent to maintain the outward appearance of this bridge even though it was taken out of service and deemed no longer structurally sound for commuter trains.

Figure 11 shows scenes from the June 2011 Bicycle Race in Manayunk. Riders at the top of the ‘wall’ (11a) and turning off Main Street to start the rigorous climb up the ‘Manayunk Wall’ (11b).

In June 2011 the 27th annual bicycle race was held in Philadelphia. It is a one-day event that covers over 150 miles with 10 laps going through Manayunk. The race has had many different names and sponsors over the years, but the course has not changed. The part of the race in Manayunk has a dramatic hill climb which is referred to as the ‘Manayunk Wall’ for its steepness of grade. I attended the first race in 1985 when I lived in Manayunk (won by Olympic speed skater Eric Heiden) and have only missed two events over the last 26 years. Before he was crowned as the Tour de France winner, Lance Armstrong made a dramatic move on the last lap on ‘the wall’ in 1993 to win the race and a large cash bonus. Each year the crowds on Main Street and the wall are large and enthusiastic. Figure 11 has images from the 2011 race. | Return to top

Figure 12 shows the old mill that was transformed into a set for the movie ‘Beloved’. It is now condominium and loft apartments.

The interesting architecture and setting have attracted three Hollywood productions to film in Manayunk. Oprah Winfrey turned one of the old mills (see Figure 12) into an outdoor set for the movie ‘Beloved’ (1998). M. Night Shyamalan shot a dramatic scene on one of the many sets of steps (Figure 13) that connect Roxborough and Manayunk in the movie ‘Unbreakable’ (2000). Several scenes were shot around the Dobson Grade School for the movie ‘Fallen’ (1998).

Figure 13. Figure 13 (a and b) shows two of the many sets of steps that connect Manayunk with Roxborough. This part of the hill is so steep that only a hand-full of streets climb the hill from the bottom up leaving many streets connected by steps.

Closing Time

The ‘Hollywood’ stage was short and appears to be over, but Manayunk continues to change. While proximity to an upscale market (Main Line) within easy driving distance was an important early factor in the revitalization of Main Street, and the commuter rail connection to center city Philadelphia and major universities (Temple, Drexel, and Penn) has been a big component of the more recent housing and residential change. The new housing, sparked by a city-wide 10 year property tax abatement, rapidly filled in empty spaces (slowed after the 2008 housing bubble crises) bring change to both the physical (style and scale; see Figure 14) and social fabric of Manayunk. Renters and college students bring a different perspective to a neighborhood than long-time residents that own their houses. It will be interesting what the future brings. Will the end of the tax abatement slow the changes or will an improved economy continue the trends? What effects will a more transient (college student renters) have on this neighborhood? What businesses will survive on Main Street?

Figure 14. (a through c) A series of photos showing the new housing recently built in Manayunk. Note how often this new housing changes the feel and scale of the smaller former worker housing surrounding it.

References Cited

Fisher, G.A. 2006. The Gentrification of Manayunk (Masters Thesis) University of Pennsylvania.

Jacobs, J 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities New York: Random House.

Lynch, K. 1960. The Image of the City Cambridge MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

Sanders, R. 2002. “Philadelphia’s Neighborhoods: A Social Geography of Manayunk and Manayunkers” In P. Rees editor Philadelphia: Transforming Tradition in the 21st Century. Philadelphia, PA: Prepared for the Joint Meeting of the National Council for Geographic Education and the Pennsylvania Geographical Society 76 – 85.

Shank, W. H. 1960. The Amazing Pennsylvania Canals York, PA: American Canal and Transportation Center.

Shelton, C. J. 1986. The Mills of Manayunk; Industrialization and Social Conflict in the Philadelphia Region, 1787 – 1837 Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Smith, Neil 1996. The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City Routledge.