“Oh what a rotten name:” Toponymic Change in Northeast Ohio

Chris W. Post, Kent State University at Stark

Abstract

In 1918, the Stark County, Ohio, Court of Common Pleas granted the village of New Berlin the legal authority to change its name to North Canton. Several such actions of anti-German sentiment occurred throughout the United States and Canada during this time, effectively minimizing the impact of German immigrants on the continent’s scriptorial landscape. This paper dissects the political and economic reasons for this particular name change in North Canton, as used in the rhetoric of, and letters received by, the W.H. Hoover Company and local newspapers. New Berlin’s change reflects two critical geographic points. First, the change symbolically annihilated the German heritage of Stark County, one of its key demographics and forces in successful agricultural and industrial development. Second, the rhetoric of the Hoover Company employed the geographic concept of scale to relate the change to 1) the war in Europe 2) the name’s impact on Hoover’s international economics, and 3) the village’s burgeoning relationship with the nearby metropolis of Canton. Despite this change, several villages and townships in the region still retained their Germanic names, an illustration of how big business can be an impetus of change on the landscape of small town America. Keywords: toponyms, Ohio, symbolic annihilation, scale

One of cultural geography’s central roles is to bring about a better understanding of how individuals and societies inscribe their cultural values and identity on the landscape. In return, this “built environment” becomes a normative agent that informs us about what we are to believe and how to live as a society (Mitchell 2000).

An integral part of the landscape is its scriptorial, or linguistic, presence that includes signs, street names, art (e.g., graffiti), and perhaps most essentially, place names, or toponyms (Alderman 2008; Berg and Vuolteenaho 2009; Drucker 1984; Gade 2003; Ley and Cybriwsky 1974). Named after people (Columbus, Washington), the natural environment (Great Falls), ideals (Independence), or other historical influences (Western Reserve, Athens), toponyms reflect and reinforce the local identities of residents and the place they create through time (Tuan 1991). Present on the landscape, maps, and in our social conscience, place names are inherently geographical and have received much attention from scholars in geography and other fields such as anthropology, sociology, and general cultural studies (Basso 1996; Bourdieu 1991; Drucker 1984). Until recently, however, little of this attention has critically analyzed the messages that are presented through the cultural landscape of place names (Berg and Vuolteenaho 2009; Monmonier 2006; Radding and Western 2010; Rose-Redwood, et. al. 2009; Zelinsky 2002).

This research builds on previous toponymic work by evaluating the name change of New Berlin, Ohio, a German-settled Midwestern town. In 1918, New Berlin (pronounced Burlin) changed its name to North Canton in a move that, superficially, appears to have been motivated by a simple desire to avoid association with German aggressions in Europe, a move not uncommon in America at the time. In New Berlin, however, interests beyond mere nationalism took on the most important role in the community’s name change.

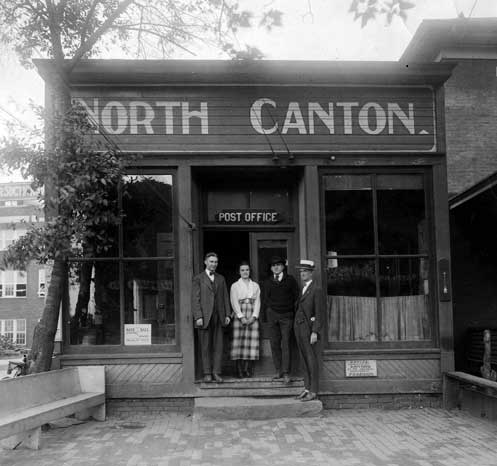

Figure 1. New Berlin Post Office in 1914 (approximation). Courtesy of North Canton Heritage Society.

New Berlin’s Origins and the Hoover Companies

Located only six miles north of Canton, New Berlin’s plat was recorded, and the village was created, on February 19, 1831 (Figure 1). Unlike its larger industrial neighbor Canton, New Berlin survived as a small farming village surrounded by a heavily German-American populace who had migrated to the area from Pennsylvania if not directly from Europe. The community remained rural and even evaded incorporation until 1876 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Location of New Berlin/North Canton in Ohio. Map by Author.

One of the early families to make a home in New Berlin were the Hoovers, who owned a farmstead east of New Berlin. In 1908 William Henry Hoover established the W. H. Hoover Company, manufacturing primarily leather products. Over time, it also fabricated sporting goods and early automobile accessories. During World War I, Hoover’s production expanded to include munitions for the war effort. More importantly, however, Hoover also started the Hoover Suction Sweeper Company which pioneered the upright vacuum and its mass production. Combined, at the start of World War I, both companies employed 500 out of New Berlin’s approximately 1,300 citizens, an astonishing rate of 38.5% (Canton Daily News, 1918a; Figure 3)

Figure 3. The former Hoover factory at Main Street and Maple Street in North Canton. Hoover's manufacturing operations recently moved to Mexico and this building now houses offices for a local community college, doctors’ offices, and other services. Photo by Author. View this photo larger.

Canton newspapers not only noted New Berlin’s industriousness thanks to the Hoover companies. More crucial to this analysis, Cantonites also praised their neighbor’s patriotism and contribution to the war effort. By February 3, 1918, New Berlin residents had purchased $86,000 worth of U. S. Liberty Bonds and 75 local young men had volunteered for Army (Canton Daily News, 1918a).

A national movement was also underway at the time to wipe German names from the American map. H. R. 11,950, introduced by Representative John Smith (R) of Michigan moved “That the names of all cities, villages, counties, townships, boroughs, and all of the streets, highways and avenues in the United States, its Territories or possessions, named Berlin or Germany to the name of Liberty, Victory, or other patriotic designation.” Obviously this bill failed. But it is worth noting that New Berlin was not alone. It was part of a large national effort to ostracize German-Americans and German heritage (New York Times 1918).

Both of these factors — patriotism and industriousness — combined to influence the town’s decision to change its name in the winter of 1918. The balance of these factors, however, is worth a deeper discussion. Simply looking at a map of Ohio and the Midwest illustrates the impact of German settlements: Frankenmuth, Michigan; New Berlin and Germantown, Wisconsin; Steubenville, Berlin, and Berlin Heights, Ohio. All of these settlements remain reflective of their German heritage. Two names, however, exist only on pre-World War I maps: New Berlin and Osnaburg, Ohio. Both are located in Stark County and both changed their names in 1918. Once New Berlin changed its name, Osnaburg followed, changing its name to East Canton. Name changes of streets, cultural relics, and towns was not uncommon during World War I. But the questions for this study is: Why New Berlin? Why 1918? What was the balance of national and economic interests in this change?

The Name Change

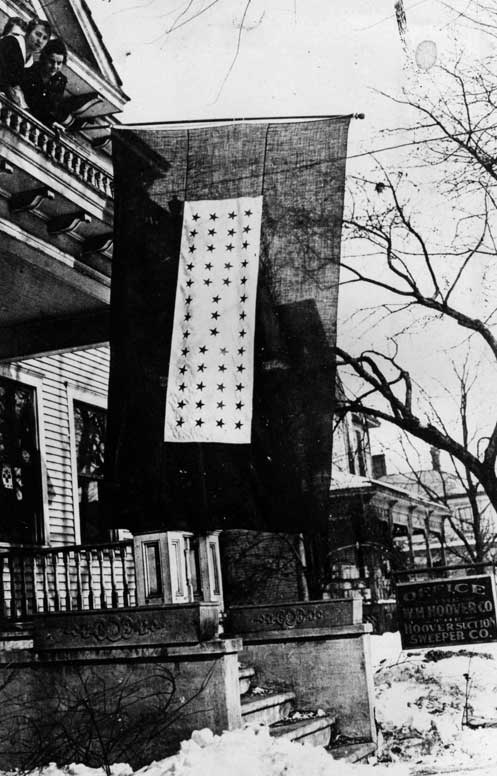

Patriotism and industry mixed constantly in the Hoover manufacturing facilities in New Berlin. W. H. “Boss” Hoover considered all of New Berlin’s Army volunteers his “boys” and took on the responsibility of informing them of their hometown’s efforts to support them and their efforts overseas (Figure 4). To this end, the Hoover Company published the Newsy News starting in September of 1917. During peacetime, the News became the company paper. Thus, it is clear Boss Hoover was aware of his business’ role in not only New Berlin, but also Stark County and Ohio.

Figure 4. A Veteran Flag flies outside the Hoover offices during World War I, indicating the number of volunteers from New Berlin and the number of those killed in action.

As the war progressed, the W. H. Hoover Company started to receive letters in reference to the name of the community it called home. These letters came from across the country and expressed concern over the name New Berlin and the identity of the company with its community. Several suggested that the company become proactive with a name change drive. One letter from the offices of Hardware Dealers’ Magazine in New York City claimed, “In the province of Ontario, Canada, before the war, there was a city called ‘Berlin.’ The citizens of that place have changed the name….It seems that you citizens of New Berlin ought to change the name of your town and we suggest that you start something.” A second letter from the Fort Lupton Light and Power Company in Colorado suggested, “P.S. why don’t you change the name of that town, Hoover and Berlin don’t sound good together.” Even the First Michigan Cavalry Association (a General George Armstrong Custer memorial association) even advised an alternative:

I am indeed sorry to know your town’s name is Berlin. For Heaven’s sake do something towards having the name changed to an American one. Oh, what rotten name, New Berlin. I suggest the name “Custer City” as General Custer was a native of Ohio being born in Ohio. See the members of your city council about the matter.

Two of these three letters came from business partners of the W. H. Hoover Company ad these disgruntled customers could take their business elsewhere if they felt that was in their best interest.

Hoover, however, was proactive prior to receiving these letters. According to Frank G. Hoover, the push for a name change was led by H. W. Hoover (also W. H's son and Frank G's father)." In February 1917, the company initiated a public petition to change the name. Titled “Concerning the Change of the Name of New Berlin,” the petition explained why the change should be made from New Berlin and to North Canton:

Because of the present war in which the United States of America is now engaged with Germany, and more especially because of the many atrocities and the frightful barbarities committed by the army of the Imperial German Government, the “Berlin” has become obnoxious to many Americans. We the following inhabitants, of New Berlin, Ohio therefore hereby express our desire that the name of our village be changed.

The petition effectively used peer pressure to influence citizens to sign. It noted that several German banks in Cincinnati had already changed their name, for example the German National Bank had become the Lincoln National Bank. In addition, it keyed in on the anti-German sentiment taking place at the national scale, saying, “Our government is doing all it can to Americanize America…every patriotic citizen would immediately adopt the new name.” Finally, it noted what repercussions may come against New Berliners if the change were not made by claiming, “Surely we will lay ourselves open to the suspicion of [b]eing Pro German rather than Pro American in our sympathies…” The question, of course, was whether or not this explanation worked for the citizens of New Berlin.

The original petition material also listed several reasons as to why the town’s future name should be North Canton. During the turn of the century, New Berlin became more economically ingrained with its larger and industrial neighbor to the south. Canton ranked as the 82nd largest city in the country in 1920 with 87,000 citizens (for comparison, that rank today belongs to Colorado Springs, Colorado; U.S. Census Bureau 1998; U.S. Census Bureau 2012). By the time of the war, Canton and New Berlin shared gas and electric lines, postal services, a rail connection, a telephone exchange, and an interurban trolley. New Berlin high school students even took classes in Canton that were not offered in their own school. The petition put it frankly and thusly, “Canton has the largest factories in the Country…most of our merchants feel that they will be more likely to attract this new trade if our name is North Canton…”

Upon filing the original petition, several regional newspapers expressed their opinions on the potential change. Both the Canton Evening Repository and the Cleveland Plain-Dealer called the New Berlin name a “stigma” (Canton Evening Repository, 1917; Cleveland Plain-Dealer 1917). The Canton Daily News claimed the town “patriotic” for both its contributions to the war effort and the move to change it’s name from New Berlin (1917b).

The original petition garnered 648 signatures, but needed 696, or three-fourths of the village’s population. Immediately after filing the original petition on 3 December, 1917, a remonstrance petition made its way around New Berlin stating:

The undersigned, being residents within the corporate limits of the Village of New Berlin, Stark County, Ohio, remonstrate against and object to the change of name of said village to the village of North Canton and represent that such change is not desirable and that such change is not desired by the three-fourths of the inhabitants if said corporation.

A total of 365 citizens signed this petition between 15 and 20 December, 1917, and it was filed on December 29. The Canton Daily News came out swinging, calling the counter movement to keep the New Berlin name an “alien symptom” that “disturbed” the local community (1917a). Still, the question of New Berlin’s name was not settled.

On 19 December, one day before all the signatures on the Remonstrance petition were collected and 10 days before it was filed, 221 citizens claimed they were unsure of what they had signed in remonstrance. These citizens signed and filed an additional petition asking that they be released from the Remonstrance Petition. This release petition read:

We, the undersigned having been hurriedly persuaded to sign a petition remonstrating against changing the name of new Berlin, now appreciate after fuller consideration that the name of our village is a handicap to the interests and growth of the Hoover Suction Sweeper Co., and the W.H. Hoover Company, and because of our being loyal American citizens, and interested in the growth of our village and its industries, hereby cancel our endorsements of the above referred to petition and that our names be with-drawn from same.

When added to the original petition, those in favor of changing New Berlin’s name had garnered enough signatures — 869; 173 more than necessary — to move forward and bring their case to the Court of Common Pleas in Canton. Judge Robert Day approved the name change to North Canton on 1 February and it was made effective on 3 February, 1918 (Figure 5). The court fee totaled $23.15 and was paid through the Canton-based law firm of Harter and Harter, who represented the Hoovers and original petitioners. A copy of the check was available in the Hoover company’s files at the North Canton Heritage Society, anecdotally indicating that Hoover paid for the legal services throughout the hearing in front of Judge Day. The Newsy News reported the change to troops in Europe immediately. In addition, the Canton Repository, Canton Daily News, and Cleveland Plain Dealer all ran extensive stories or editorials about the name change. The Canton Daily News ran an entire section on North Canton’s new identity, its contribution to the war effort, and the impact of the Hoover companies on the village (1918b). It ran an additional editorial calling North Canton an “enterprising little community,” a “hot bed of pure American patriotism,” and saying that it possessed an “inspiring zeal” thanks to the name change (Canton Daily News, 1918a). H. W. Hoover even wrote a short piece of his own in the Newsy News for the troops in Europe on 6 February (1918).

Figure 5. North Canton Post Office after the name change, 1919 (approximation). Courtesy North Canton Heritage Society.

Again mail flooded the Hoover offices, this time in gratitude of the change. As one letter praised, “Hooray North Canton, All true Americans will admire your citizens for the Patriotic spirit in changing your name to the above. It will greatly assist the ‘Hoover Suction Cleaner Co.’ in its efforts to put your town on the great map again say I.” Even U. S. Senator Atlee Pomerene wrote the company in sincerity. Another letter came from Captain Charles R. Morris, a Quartermaster in the War Department, who looked forward to “an opportunity to…tell [the Kaiser] that Mr. Hoover and fellow citizens have wiped New Berlin off the map.” Hoover’s work paid off. It called North Canton home and criticism turned to praise.

Analysis

The United States has played home to many ostracized groups throughout its history: the homeless, poor, American Indians, African Americans, Japanese Americans and women have been but a few. European groups less frequently have experienced such marginalization, though some groups, such as the Irish, have experienced such marginalization (Marston 1989). Due to World Wars I and II Germans and German-Americans became the target of extreme xenophobia. Threats and actions made against German heritage by the American public revealed themselves on the cultural landscape via many changes, particular in place names. Even street names changed. Berlin Street in New Orleans, according to a 1908 map from the Perry-Casteñeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas (http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/united_states/ new_orleans_1908.jpg) became General Pershing Street. In Ohio alone, several towns changed their names in addition to New Berlin. As mentioned above, Osnaburg changed its name to East Canton. In addition, Berlin in Shelby County switched to Fort Loramie. New Berlin was, thus, not alone. Its name change, however, offers an opportunity to study an uncommon confluence of several geographic concepts: language, landscape, scale, symbolic annihilation, and symbolic capital.

Beyond the concept of landscape and language’s presences on it, as covered in the introduction, the concept of scale stands crucial to this particular study and underlines that no landscape is built or changes merely at one geographical level (Herod 2010; Mitchell 2008). In all these examples, particularly New Berlin, local officials made these toponymic changes in response to global events. Due to the fact that several communities throughout the country, especially in the Middle West, made these change almost simultaneously adds the element of a national scale phenomenon.

The name change’s effect on the German imprint throughout the Middle West is clear: it actively erased a component of heritage that this large collection of European groups contributed to America. Jennifer Eiscthedt and Stephen Small’s concept of “symbolic annihilation” identifies this action nicely. According to these two sociologists and their work on sites of Southern heritage, preservation managers minimized the role of African American slaves on plantations and other large urban estates (2002). The lives of slaves were effectively annihilated from memory and visitors subsequently reproduce this same cultural “amnesia” (see also Alderman and Campbell 2008). New Berlin’s name change does the same to the role of German Americans in establishing Stark County in general and North Canton in particular. The new name eliminated that role in a real and potentially material way by obliterating it from the landscape (Foote 2003).

Finally, the change from New Berlin to North Canton also illustrates the role of symbolic capital in making such changes in the cultural landscape. According to Pierre Bourdieu, symbolic capital is “…those practices and goods that are defined as socially distinctive, desirable and powerful” (Alderman 2008; Bourdieu 1991). The Hoovers and the New Berlin community at large, including the village council, saw their town’s name as a burden on how their home was perceived. They saw the potential for change as a positive move to unload this burden in the midst of global conflict. They saw it as both a literal and figurative investment in their community and their identity with it.

Concluding Thoughts

Geographically, place names are potent symbols of identity, territory, and cultural, economic, and political power. Their presence on the landscape, on maps, and in our everyday written and verbal communications make them effective normative agents. Historically speaking, of all the immigrant groups in American history, Europeans and their descendants have experienced the least marginalization. The history of North Canton, Ohio, brings both of these historical geographic axioms to a confluence. If not for Hoover and its active role New Berlin may still be on the toponymic landscape of Ohio and America. Instead, only a single laundromat still displays the New Berlin title (Figure 6). Indeed, the heritage of New Berlin has been nearly annihilated.

Figure 6. New Berlin Bubbles and Suds, the only landscape evidence that remains of North Canton's historical identity. Photo by Author. View this photo larger.

References

Alderman, Derek H. 2003. “Street Names and the Scaling of Memory: the Politics of Commemoriating Martin Luther King, Jr., within the African American Community.” Area 35 (2): 163-173.

_____. 2008. “Place, Naming, and the Interpretation of Cultural Landscapes.” The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity, Ashgate Press (edited by Brian Graham and Peter Howard), pp. 195-213.

_____, and Rachel M. Campbell. 2008. “Symbolic Excavation and the Artifact Politics of Remembering Slavery in the American South.” Southeastern Geographer 48 (3): 338-355.

Basso, Keith H. 1996. Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language Among the Western Apache. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico.

Berg, Lawrence D. and Jani Vuolteenaho, eds. 2009. Critical Toponymies: The Contested Politics of Place Naming. Ashgate Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press). Edited and Introduced by John B. Thompson, translated by Gino Raymond and Matthew Adamson.

Canton Daily News. 1917a. “Fight Plan to Rename New Berlin.” December 23. p. 1.

_____. 1917b. “New Berlin Renounces Teuton Name.” December 3. p. 1.

_____ 1918a. “North Canton.” p. 6.

_____. 1918b. “North Canton: Livest Village In U.S., Known to World.” 3 February. Second Section, p. 15.

Canton Evening Repository. 1917. “War Causes New Berlin to Seek Name of North Canton.” December 3. p. 1.

Cleveland Plain-Dealer. 1917. “Off with the Old.” December 7. p. 15.

Drucker, Johanna. 1984. “Language in the Landscape.” Landscape, 28: 7-13.

Eichstedt, J. and S. Small. 2002. Representations of Slavery: Race and Ideology in Southern Plantation Museums. Washington, D.C: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Foote, Kenneth. 2003. Shadowed Ground: America’s Landscapes of Tragedy and Violence, 2nd Ed. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Gade, Daniel. 2003. “Language, Identity, and the Scriptorial Landscape in Quebec and Catalonia.” Geographical Review. 93 (4): 429-448.

Herod, Andrew. 2010. Scale. New York: Routledge.

Ley, David and Roman Cybriwsky 1974. “Urban Graffiti as Territorial Markers.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 64 (4): 491-505.

Marston, Sallie A. 1989. “Public Rituals and Community Power: St. Patrick’s Day Parades in Lowell, Massachusetts: 1841-1874.” Political Geography Quarterly 8 (3): 255-269.

Mitchell, Don. 2000. Cultural Geography: A Critical Introduction. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

_____. 2008. “New Axioms for Reading the Landscape: Paying Attention to Political Economy and Social Justice.” In Political Economies of Landscape Change, eds. J.L. Wescoat and D.M. Johnston, 29-50. New York: Springer Publishing.

Monmonier, Mark. 2006. From Squaw Tit to Whorehouse Meadow: How Maps Name, Claim, and Inflame. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

New York Times. 1918. “To Strike Germany From Map” of U.S. June 2.

Hoover, H. W. 1918. “To all the Boys with the Colors.” The Newsy News. February 6. p. 2.

Radding, Lisa, and John Western. 2010. “What’s in a Name? Linguistics, Geography, and Toponyms.” Geographical Review. 100 (3): 394-412.

Rose-Redwood, Reuben, Derek Alderman, and Maoz Azrayahu. 2010. “Geographies of the Toponymic Inscription: New Directions in Critical Place-Name Studies.” Progress in Human Geography (Forthcoming; available online November 27, 2009).

Tuan, Yi-Fu. 1991. “Language and the Making of Place: A Narrative-Descriptive Approach,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 81: 684-696.

U. S. Census Bureau. 1998. 1920 Decennial Census Table 15: Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places. Accessed Online, March 9, 2012. Internet Release Date: June 15, 1998. URL: http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0027/tab15.txt

U. S. Census Bureau. 2012. 2010 Decennial Census Table 20: Statistical Abstract of the United States. Accessed Online: March 9 2012. URL: http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2012/ tables/12s0020.pdf

Zelinsky, Wilbur. 2002. “Slouching toward a Theory of Names: A Tentative Taxonomic Fix,” Names, 50: 243-62.

Author Biography

Chris Post is Assistant Professor of Geography at Kent State University’s Stark Campus in North Canton, Ohio. His research interests center on commemoration, heritage, company towns, and past places. He has yet to wash any clothes at the New Berlin Bubbles and Suds.