The Philadelphia Corner Store

Lynn Alpert

The corner store is a commercial structure on an otherwise residential block within a residential neighborhood. It is part storefront and part row house. This distinct combination was created to serve the needs of residents on the periphery of city centers in a specific historical moment, the latter half of the nineteenth century into the early twentieth century. The corner store is still a common aspect of urban neighborhoods in the United States today, including many in Philadelphia. Bodegas along with small shops, restaurants, and bars bring vibrance and vitality to Philadelphia’s row house neighborhoods. They are economic drivers and support an active street life. At the same time their extant historic fabric is a visual reminder to residents and visitors of the history of these neighborhoods and can help them to understand the integral role these properties played in the development of the city. Though their uses have changed greatly over time, corner stores are finding new lives as people again are appreciating the benefits of walkable urban neighborhoods and begin to reuse these stores which were so important to the building of these communities over a hundred years ago.

Defining the Corner Store

The design of the typical corner store has been explored extensively in studies of commercial architecture (Figure 1). Corner stores are house-over-shop commercial structures as exemplified by architectural historian Richard Longstreth in his guide to American commercial architecture (1987). These buildings have existed since antiquity in use, but did not become prevalent as a noticeable and designed type until the early 19th century. Shop-houses express their two uses through a clear division between commercial use on the ground floor and residential use above. This is expressed visually on the façade through different treatments of the first and upper stories. The first stories of most historic corner stores have a canted corner entrance that is low to the ground, as compared to the front-facing entrances of adjoining row houses that are raised several feet above ground level for privacy. Corner stores also have large picture windows on the first floor which are located at eye level for the easy display of goods, while the upper stories contain smaller double-hung windows. This division is solidified visually through a first-story cornice that separates the retail space below from the private residential space above.

Figure 1. Corner store, 1713 Wolf Street, Philadelphia. Photograph by the author.

What sets the corner store apart from this well-studied type is location. Longstreth begins his study by narrowing his scope to strictly commercial areas (1987). The house-over-shop buildings that Longstreth defines are, inherent to his scope, located on commercial strips or main streets, separated from purely residential areas. The corner store, placed within an otherwise residential zone, is an anomaly in Longstreth’s strictly segregated urban environment. Yet research shows that this residential-commercial mix was not an anomaly at all; it was the norm for these mid-nineteenth through the early twentieth centuries row house neighborhoods. These stores served many needs in their communities. They were typical corner groceries as well as butcher shops, bakeries, dairies, hardware stores, barber shops, and bars.

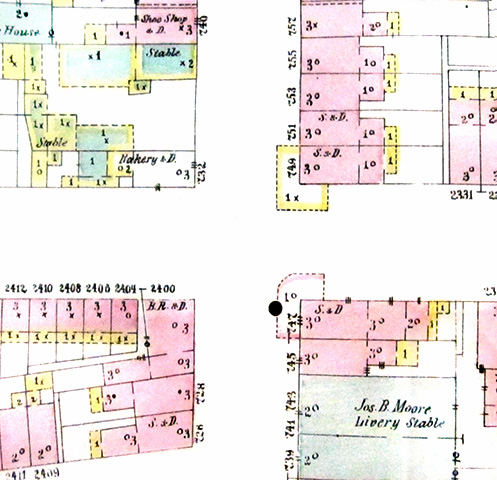

Historic maps show that corner stores were common in Philadelphia’s residential neighborhoods by the mid- to late nineteenth century (Figure 2). The neighborhoods that contain these stores were some of the first suburbs of Philadelphia. Though technically located within the city limits, they were a part of a trend of urban expansion that was taking place in cities all over the country. Expansion was possible due to advances in transportation and industrialization which led to an influx of workers to cities. Corner stores served the needs of the residents of these newly-formed neighborhoods. This historic pattern of residential development, which placed commercial uses on most corners, can still be seen in the built fabric today. It was prevalent enough still in the 1960s to have left a lasting mark on the city’s zoning code, which was still in use until August of this year, when the city finally adopted an entirely new code. Many corner properties in residential neighborhoods were still zoned as C1, “Mixed-Used ‘Corner Store’ Commercial” properties up until that time and commercial uses are still seen in many neighborhood corner stores today.

Figure 2. 1876 Hexamer Insurance Map of 24th and Aspen Streets in the Fairmount section of Philadelphia. Map Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia.

It may seem odd to us today that such a large number of stores were necessary in these neighborhoods, but there were many reasons for their proliferation. First, the advances in transportation that created these new neighborhoods were not as life-changing as later inventions, such as the car, would be. Though omnibuses and trolleys made it easier for people to travel to and from work, they could be expensive and time consuming and would therefore not necessarily be utilized for shopping. Also, before refrigeration people still needed to shop every day for groceries, and this was not a one-stop shop. Meals were collected from the grocer, the butcher, the bakery, the dairy shop, and the produce market (Beasley 1999; Liebs 1985). As many housewives were not taking the new modes of transportation into the city center, the ability to walk from home to all of these stores was essential. Corner stores also housed local pharmacies, hardware stores, and general stores. Corner bars and saloons were hallmarks of many of these neighborhoods as well. In working-class neighborhoods in particular, the corner bar often doubled as a community center (Kingsdale 1973). Saloon-keepers were often seen as leaders in the community, and the saloon was one of the few places that locals could go to use a telephone, as well as to find out game scores, pick up mail, and cash a check (Sismondo 2011). As many of these bars were divided along ethnic, racial, and class lines, they were also extremely localized institutions and the majority of neighborhoods had at least one saloon for every block (Sismondo 2011). For all of these reasons, commercial properties on every corner were necessities in these early suburbs.

As the twentieth century progressed, many threats to corner stores, and to the neighborhoods that housed them, developed. The invention of the car had strong effects on commercial architecture and the segregation of commercial uses from residential (Cutler 1980). Cars provided greater freedom of mobility and choice of neighborhood than had ever existed before, and people of means began leaving dense urban neighborhoods for the less-populated suburbs beyond the city limits (Cutler 1980). This “white flight” from urban neighborhoods coincided with other technological advances that significantly changed how people lived and shopped. New large-scale assembly line manufacturing meant that products were more affordable and more widely available (Blumin 1985). People no longer shopped in small stores, but in larger one-stop groceries and department stores, and cars made it possible to fully segregate these new commercial uses from residential neighborhoods, rendering the corner store obsolete in new suburban neighborhoods. By the mid-twentieth century, franchise stores were also becoming the norm, replacing smaller independent retailers (Satterthwaite 2001). In addition, larger groceries and chain stores often require specific floor plans and layouts that do not fit physically within the confines of historic structures. When these stores replace smaller independent stores in urban neighborhoods they cannot move into the historic buildings that many of these independent stores inhabited and must instead demolish and build new or move to other areas, leaving corner commercial buildings vacant. This problem, compounded by the urban disinvestment of the urban renewal period, left a great number of corner stores neglected by the end of the twentieth century.

Philadelphia’s Corner Stores Today

Not all Philadelphia neighborhoods were victims of white flight and urban renewal. As such, the corner stores of different neighborhoods are in different states of preservation, disrepair, and use depending on what changes these neighborhoods went through over the past fifty years. For instance, in neighborhoods that suffered a good deal of abandonment, many corner stores retain historic architectural details but are in serious states of disrepair and are often vacant (Figure 3). In areas that have seen a lot of recent renewal and gentrification, corner stores have been stripped of much of their extant fabric. Though some have been reused as commercial properties, these are often upscale bars and restaurants, and many first stories have gone through extensive changes to be converted to complete residential use (Figure 4). In some areas, though, residents of fifty or sixty years ago still remain. The stores in these neighborhoods continue to be used as butcher shops and bakeries, pharmacies and barber shops, but they have often lost much of their original fabric in the interest of “updating” or “modernizing” the exterior (Figure 5). Though they exist in these various states of preservation and use, corner stores remain ubiquitous elements of their historic neighborhoods.

Figure 3. An abandoned corner store that has retained some historic fabric in South Philadelphia. Photograph by the author.

Figure 4. A residential conversion in Queen Village. Photograph by the author.

Figure 5. A corner store with extensive contemporary renovations in South Philadelphia. Photograph by the author.

A closer examination of the history of one corner store in the Fairmount Neighborhood illustrates how these broad trends in American history took shape on the ground in Philadelphia. Some corner stores are still in use in Fairmount, as pharmacies and corner bars, as well as yoga studios, cafes, and medical offices, but a significant number of these buildings have been converted to residential use on the first story. The dwelling at 829 North 26th Street currently looks like a typical Philadelphia row house, but when it was completed in 1876, the first story contained many storefront details (Franklin Fire Insurance Company of Philadelphia 1876) (Figures 6 and 7).

Figure 6. 829 North 26th Street as it looks today. Photograph by the author.

Figure 7. A storefront on Brown Street in Fairmount. The extant details are similar to what 829 North 26th Street would have looked like in 1876. Photograph by the author.

A Franklin Fire Insurance Company survey of the building, survey number 52385 completed for John Lyons on May 3, 1876, confirms that there was a store in the front half of the first story as early as that date. It also gives a detailed description of the storefront. Originally the building had a corner entrance that was angled at 45 degrees from the façade, with double doors and a transom above, as well as marble steps. The upper stories of the building cantilevered over the entrance, forming a small covered porch which was supported with a cast-iron column. Side lights and pilasters flanked the entrance and a cornice with frieze extended across the length of the west façade and continued along the south façade to the end of the doorway. These architectural details represent many of the defining characteristics of Philadelphia’s historic corner stores and of house-over-shop commercial architecture.

Upon closer examination of the current structure, it is not too difficult to see the traces of this original commercial design. The front entrance, though no longer canted, is only two steps up from the sidewalk (see Figure 8). This is much lower than the entrances of the adjoining residential properties, as was common for storefront entrances. What would have been the historic storefront area has been faced in a layer of brick that is clearly from a different period than the brick on the upper stories and which projects out from the flat plane of the original façade (see Figure 9). This brick covers the entire first story of the west façade and continues along the south façade for several feet, a space that clearly correlates to the area of the storefront described in the 1876 survey. The entire area is capped by a synthetic shingle awning which also correlates to the historic cornice and frieze location. Many of the historic storefronts in Fairmount have undergone these changes as more and more historic shop-houses have been converted to residential use.

Figure 8. Detail of the front entrance at 829 North 26th Street. Photograph by the author.

Figure 9. Detail of the projecting brickwork where 829 North 26th street meets the neighboring row house. Photograph by the author.

The building at 829 North 26th Street is located in what is now known as the Fairmount, or Art Museum, neighborhood. Historically it was a part of the Penn District. As the district grew, it attracted inhabitants from many social classes and is an example of the socioeconomic mixing that was still evident in Philadelphia’s suburbs into the late 19th century (Gillette 1980). The area attracted more proprietary workers as it grew, but by 1880 artisans still outnumbered them (Gillette 1980). The Penn District is marked by the standardized lots and speculative rows that would dominate urban expansion in America at this time, and historic maps show that corner stores and corner bars opened up almost as quickly as parcels could be subdivided, developed, and sold (Hexamer and Locher 1859; Hexamer 1876). The neighborhood was built up over the latter half of the 19th century. Like the property at 829 North 26th Street, the majority of these corner properties were likely designed to express their commercial use on the exterior.

Like many corner stores, this one went through multiple changes in ownership, occupants, and use over time. John S. Miller, a German immigrant, was the first long-term owner of the property (U. S. Census Bureau 1880). Miller was a grocer who lived with his family at 827 North 26th Street, just across the street from 829 North 26th Street, and likely ran his grocery business from the first story of the building (U. S. Census Bureau 1880). Miller was successful enough in his business to purchase the property across the street as a rental property. One of the earliest tenants in the building was the Brill family. John Brill was a Prussian immigrant who ran a tavern, likely the bar room that is listed as the first-story use of the building on an 1876 Hexamer map (U. S. Census Bureau 1880).

The Miller family continued to have success. By 1900 they owned three of the four properties at the intersection of 26th and Parrish Streets (U. S. Census Bureau 1900). 829 North 26th Street had new tenants by this time. The first story changed from a bar to a shop, though the particular use is unclear, and the upstairs was being run as a boarding house (U. S. Census Bureau 1900). In 1910 the shop was more specifically in use as a drugstore (U. S. Census Bureau 1910). The proprietor of the store, Otto Kraus, moved to Philadelphia to attend the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and Science (U. S. Census Bureau 1910; England 1922). Of German descent, but born in Connecticut, Kraus purchased the property from Miller’s daughter, Ida Ostertag, on June 28, 1916 (Philadelphia Deed Abstracts). By 1920 two of Miller’s daughters, who had been living at Parrish and 26th and running their father’s grocery business up to this point, had both retired and moved to the more remote suburb of West Philadelphia (U. S. Census Bureau 1920).

Otto Kraus owned this property until 1945, when he and his wife sold it to Theordore Ziegler, and it is likely that he continued to run his drug store there until this time (Philadelphia Deed Abstracts). In 1950 the property was still being used as a shop, but by 1958 it had been converted to residential use (Sanborn 1917; Sanborn 1950). This early change from a shop-house to a dwelling may explain the severe loss of historic fabric related to the storefront. Many corner stores in the area were still operating as shops as late as 1958, including the Millers’ old property on the northwest corner (Sanborn 1917). Still, early conversions to residential use such as this may have set a precedent in the neighborhood for the complete removal of storefront fabric when making this type of alteration.

Conclusions

Fairmount has changed greatly over the past twenty years, but a number of Fairmount’s historic corner stores are still in use as businesses. There are a few pharmacies and bodegas in the area, but the one traditional use that has stood the test of time is the corner bar. The area gentrified rapidly over the past few decades, and upscale bars and restaurants within walking distance, and generally located in historic corner storefronts, have given the area appeal to young people who may have grown up in the suburbs but have decided to live in a city. The neighborhood is vibrant and walkable, and is made safer due to the active street life that these bars and restaurants promote. In this way, corner stores are now serving many of the same purposes that they did when they were first built. They offer services that meet the specific needs of their residents and therefore attract more people to the city. They also reflect the specific history of these early suburbs in a time when dense and walkable neighborhoods are on the rise. In this way, their historic purpose is being reborn and helping to bring these neighborhoods back to life.

References Cited

Beasley, E. 1999. The Corner Store: An American Tradition, Galveston Style. Washington, DC: The National Building Museum.

Blumin, S. M. 1985. “The Hypothesis of Middle-Class Formation in Nineteenth-Century America: A Critique and Some Proposals.” American Historical Review, Vol. 90, No. 2. Bloomington, IN: American Historical Association.

Cutler, W. W., III. 1980. “The Persistent Dualism: Centralization and Decentralization in Philadelphia, 1854-1975.” In W. W. Cutler, III and H. Gillette, Jr., eds. The Divided Metropolis: Social and Spatial Dimensions of Philadelphia, 1800-1975. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

England, J. W., ed. 1922. The First Century of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy, 1821-1921. Philadelphia: Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and Science.

Franklin Fire Insurance Company of Philadelphia. Surveys 1829-1901. Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Gillette, H., Jr. 1980. “The Emergence of the Modern Metropolis: Philadelphia in the Age of Its Consolidation.” In W. W. Cutler, III and H. Gillette, Jr., eds. The Divided Metropolis: Social and Spatial Dimensions of Philadelphia, 1800-1975. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Hexamer, E. 1876. Maps of the City of Philadelphia, Vol. 6. Philadephia: Ernest Hexamer.

Hexamer, E. and W. Locher, eds. 1859. Maps of the City of Philadelphia, vol. 6. Philadelphia: E. Hexamer & W. Locher.

Kingsdale, J. M. 1973. “The ‘Poor Man’s Club’: Social Functions of the Urban Working-Class Saloon.” American Quarterly Vol. 25, No. 4. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Liebs, C. H. 1985. Main Street to Miracle Mile: American Roadside Architecture. Boston: Little Brown.

Longstreth, R. W. 1987. The Buildings of Main Street: A Guide to American Commercial Architecture. Washington, D.C.: Preservation Press.

Philadelphia Deed Abstracts. Philadelphia City Archives.

Sanborn Map Company. 1917. Insurance Maps of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Vol. 4, Rev. 1958. New York: Sanborn Map Company.

---. 1950. Philadelphia 1916-May 1951, Vol. 4, Rev. 1950. Philadelphia: Sanborn Fire Insurance Map Company.

Satterthwaite, A. 2001. Going Shopping: Consumer Choices and Community Consequences. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sismondo, C. 2011. America Walks Into a Bar: A Spirited History of Taverns and Saloons, Speakeasies and Grog Shops. New York: Oxford University Press.

United States Census Bureau. 1880. Population Census, Philadelphia, PA. http://ancestry.com, last accessed 8 March 2012.

Author Biography

Lynn Alpert is an Architectural Historian at Richard Grubb and Associates in New Jersey and recently earned her M.S. in Historic Preservation from the University of Pennsylvania. Her research interests concentrate on urban vernacular architecture, both in the United States and abroad.