The James Library: House of Knowledge

Siobhan Fitzpatrick, Curator of Collections and Exhibits, Museum of Early Trades and Crafts

Figure 1. Exterior view of the James Library, now the Museum of Early Trades & Crafts, located in Madison, NJ, which was built in the Richardson Romanesque Revival Style.

The James Library (Figure 1) is located in Madison, New Jersey. It was built and donated to the town by one of Madison’s best-known residents, D. Willis James. As with many of Manhattan’s elite in the late nineteenth century, he was attracted to the bucolic setting of Madison and eventually built a country house in the town. Always interested in philanthropic and educational work, James had been president of the Children’s Aid Society, a trustee of Amherst College and benefactor of several institutions, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York Times 1907). Beginning in the 1880s he turned his attention to the town of Madison, first creating a park for the town and then setting about the creation of the town’s first free public library. Construction of the library began in 1899 and was completed in 1900. His motivation to build the library was two-fold; to give back to the residents of Madison and to educate newly arrived immigrants who worked in the area’s burgeoning rose growing industry. Ultimately the interior decorative motifs of the Madison’s first free public library, which soon after its opening became known as the James Library, reflects the founder’s desire to provide space for learning and educating the public.

The library was designed by the architectural team of Charles Brigham and Willard Adden. While both are well known independently for work on other buildings, their partnership was short-lived; in fact there are only two other known projects that they collaborated on, the James Mercantile Building (completed in 1899), which stands opposite the James Library, and the Atlantic Avenue Station of the East Boston Tunnel, run by the Boston Transit Commission (Delaney 2012). In much of their work, including the James Library, these Boston-based architects followed the increasingly popular Richardsonian Romanesque Revival Style. Developed by Henry Hobson Richardson, this style was characterized by massive stone walls with rough cut sides, extensive use of semicircular arches, and a dynamic new use of interior space (Howe 1998).The decorative details on the building, including all the stained glass and stenciled brick, was completed by the A.B. Cutter Company, another Boston-based organization. It was run by the owner, Arthur B. Cutter, who had received training in a variety of decorative arts, including tile painting and the art of stained glass.

James’ decision to hire Bostonians versus New Yorkers may help to account for the stylistic differences seen in the James Library versus other public buildings in the New York area at the time. While Boston was strongly influenced by the Richardsonian Romanesque Revival, New York tended to favor the Beaux Arts style for many of its public buildings, especially those dedicated to learning, at the turn of the century. The Beaux Arts style which was imported from France by such architects as Richard Morris Hunt, was highly formal, monumental in size and offered extensive decorative details. It was favored for its ability to deliver a strong symbolic message (PHMC 2013).The James Library has ultimately benefited from a preservation standpoint, with its distinction as one of the best examples of Richardsonian Romanesque Revival style in the state of New Jersey.

The library has several motifs that appear throughout the building, including repetitive floral designs and carved stone supports. The figure of the torch appears in the stained glass windows, on the front of the stacks, and along the balcony railings and represents the promotion of education. In the ancient Greek myth of humanities origins, Prometheus, who molded man from clay, steals fire from the gods and brings it to earth where he teaches man how to use it. Of course Prometheus is punished for his actions, but knowledge and technology derived from fire, remain. Thus, in art and architectural embellishments the torch is literally the spark of knowledge as it symbolizes the embrace of knowledge or the advancement of technology. This symbolism is especially appropriate for a library. The James Library further emphasizes the significance of knowledge by pairing the torches with laurel wreathes, symbols of victory and achievement. Also incorporated into the design to promote education are the schools’ seals which appear on the arch above the double doors leading into the Trustee’s Room. These seven seals represent the original seven colleges in the American colonies. From left to right they read Columbia University (1754), University of Pennsylvania (1740), the College of William and Mary (1693), Harvard University (1636), Yale University (1701), Princeton University (1746) and Queen’s College (aka Rutgers University) (1766) (METC 2012). The original institutions of higher learning in the United States all predate the nation itself; striving for admission to one of these schools was the ultimate educational inspiration that the library could offer.

The building also has many decorative quotes which relate to the promotion of education. These quotes are taken from a wide range of individuals, including many still familiar to modern readers, such as William Shakespeare, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Others are from individuals who were well known at the end of the nineteenth century but have since faded from popular memory, including Edwin Percy Whipple, Herbert Spencer, and Edward Bulwer-Lytton. Altogether the building has a total of twenty-five quotes which can be divided into four main themes: Science & Technology, Religion & Philosophy, Language, and Politics. The majority fall into the two categories of Religion & Philosophy and Language.

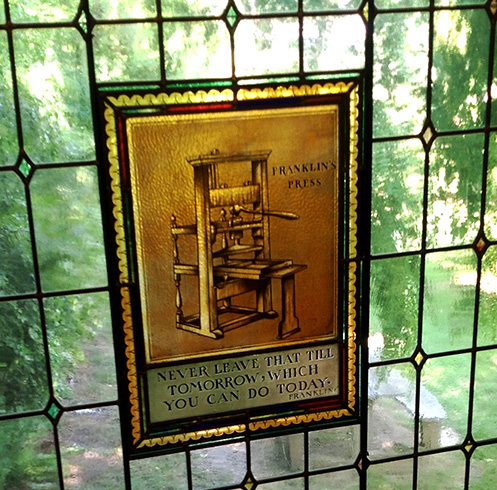

Of the four main themes, Science & Technology contains the fewest quotes, but the stained glass windows that represent those themes are among the most beautiful in the building. This theme does contain one quote by an American, Benjamin Franklin: “Never leave that till tomorrow, which you can do today”(This quote and all others are copied as they appear in the James Library). While Franklin’s famous saying is still well known, even by modern audiences, the illustration of the quote proves far more illuminating. The window prominently features a Franklin printing press (Figure 2). The image is associating Franklin with his work as a printer, and the printing industry that aided American growth and educational development, rather than focusing on his work in politics or scientific inquiry (Wood 2004).

Figure 2. One of the many stained glass windows in the James Library, this window section features a quote from Benjamin Franklin and is illustrated with a Franklin Printing Press.

The next theme is politics. Most of the political quotes revolve around the need for educating the masses, part of the library’s mission. From Horace Mann, major advocate for mass education (Finkelstein 1990), comes the quote, “Education is our only political safety.” This was not a new concept; the idea dates back well over two thousand years with one of the earliest statements coming from the Roman writer Dionysius, “The foundation of every state is the education of its youth” which also appears in one of the museum’s windows. Mann’s quote is illustrated with a simple heraldic device with a center image of an open book reading ‘veritas’ or truth. The image suggests that truth or knowledge can be found through reading. The Dionysius quote, on the other hand, uses slightly more complex imagery. It features a young man in robes or perhaps a cloak -covered toga being lead forward by a winged woman carrying a lantern. The woman, who looms larger than the youth, is a Christianized interpretation of Muse or Knowledge. The lantern forms a symbolic connection with the torch motif and the myth of Prometheus.

The other two quotes that involve politics or political figures are “They are never alone that are accompanied by noble thoughts” from Philip Sidney, a writer and political figure during the reign of Queen Elizabeth during the sixteenth century (Hamilton 1977), and “Music is a stimulant to mental exertion” by Benjamin Disraeli, a political figure of Jewish ancestry in the nineteenth century (Bloy 2012). Both of these quotes suggest that classical learning, either through musical education or other general learning, will improve the ‘quality’ of the person. The Disraeli quote is accompanied by an image of a woman playing a lyre. The image suggests that she may be one of the muses, a fitting inspiration for anyone trying to learn. The Sidney quote is located in a center window arch accompanied by a quote by Theodore Parker (discussed below). The space allows for little ornamentation but it does contain floral borders and a small circular image at the top featuring an owl sitting atop a stack of books. The owl traditionally has been a symbol of wisdom and books representative of knowledge or learning.

The connection between the Sidney and Parker quotes brings us to the third theme, religion and philosophy. Sidney and Parker make an unusual pair; they did not share a country, a century or a religion. But perhaps what could be said of them is that they did share a love of knowledge and learning. Parker’s quote, “The books that help you most are the books that make you think the most,” reflect his role as both one of the nineteenth century’s most influential ministers whose congregants included Julia Ward Howe, Louisa May Alcott, and Thomas Wentworth Higginson, and also his role in the Transcendentalist Movement (Grodzins 2002). He also has the distinction of being one of the few Americans selected for inclusion in the library. But he does not stand alone — also included are two quotes from the Unitarian preacher William Ellery Channing, who rose to prominence during the Second Great Awakening in the 1830’s and was highly influential for the Transcendentalism Movement, even though he did not approve of it (Channing, 1899). His two quotes remain un-cited in the library. Of the two the one which directly relates to learning appears carved on the fireplace mantel. The quote reads, “God be thanked for books; they are the voices of the distance and the dead, and make us heirs of the spiritual life of past ages.” This quote comes from a longer statement that promotes reading for religious enlightenment among all classes, and would have been prominently visible by anyone visiting the library.

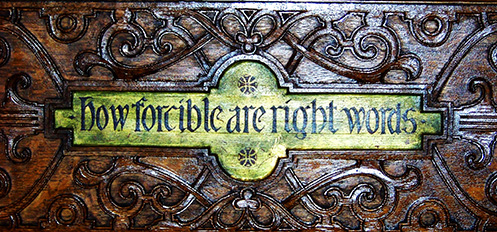

The library also uses three biblical references, two of which relate directly to learning: “Happy is the man that findeth Wisdom, and the man that getteth Understanding” (Proverbs 3:13) and “How forcible are right words” (Job 6:25). Within a library setting their intent would imply the pursuit of knowledge and its use for higher purposes. Both of these quotes appear without illustration, perhaps because biblical passages would have been so well known to a late nineteenth century audience it was deemed unnecessary to clarify the intent with allegorical or symbolic figures (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Interior detail from the mantel in the Trustee’s Room of the James Library, it features a biblical quote from the Book of Job, related to the power of words and knowledge.

The last two quotes I wish to discuss are by Francesco Petrarch, the father of humanism (Reeve 1878), and Edward Bulwer-Lytton, a British Victorian writer famous for his poetry, plays and novels, who also served in the English Parliament and became involved in several reform movements. While Petrarch is still widely regarded, Bulwer-Lytton remained a person of importance only until the beginning of WWI when his literary, social, and political importance began to fade from memory due in large part to criticism of his ponderous writing style (Bulwer-Lytton, 2006). Petrarch’s quote reads “Glory is acquired by virtue; but preserved by letters.” Petrarch was noting the transition from an oral to a literate society. While being virtuous might be enough to bring glory to your family, only a written record would ensure a lasting memorial. By the close of the nineteenth century this would ring especially true and act as a warning to library patrons. Petrarch’s quote also uses a variation on the heraldic device, and prominently features a laurel wreath in the center. Traditionally laurel wreaths were awarded to great heroes and artists for service to their respective communities in ancient Greece. Military leaders also wore them after major victories in ancient Rome, and thus the laurel wreath tended to symbolize the achievement of glory. Bulwer Lytton’s quote reads, “The pen is mightier than the sword.” Used for many purposes, including promoting education and advocating peaceful rather than violent protest, these words have developed a complex and layered meaning for a modern audience that makes it difficult to determine their meaning to a late nineteenth and early twentieth century audiences. Placement within a library would indicate that the quote was being used to encourage education, suggesting that even the strongest person might be defeated by an educated man. The quote is accompanied by a rather simple image, a quill pen tied to a scroll; though the scroll has no writing, it is implied that the pen will soon be used for just that purpose.

James’ building remained the town’s library for over sixty years, but by the 1960s the collection had grown too large, and the needs of the town had outgrown the space. As a result a new building was built on acreage with land to expand. When the new building opened in 1969 the James Library closed to the public and its contents were transferred to the new branch. In 1970 the Museum of Early Trades and Crafts (METC) began leasing the building from the Borough of Madison and continues to do so (Delaney 2012). The interior of the building saw some changes while still being used a library. Before World War II the unfinished basement rooms were “fitted out with drywall and repurposed as finished spaces,” and after WWII a bridge was installed joining the “two mezzanine levels used for the upper stacks, replacing a staircase to the mezzanine on the side near the tracks” (Delaney 2012, 6). More dramatic changes were made when the building became a museum. For the Bicentennial “partitions were installed on the main floor… and a drop ceiling was installed over approximately 2/3s of the main floor to create an attic level for storage;” and then in 1987 part of the lower levels were converted into exhibit space as well (Delaney 2012, 6).

In 1993 the METC began restoration of the building, in part with a New Jersey Historic Trust Grant. Early efforts focused on exterior restorations and preserving the stained glass windows, but in May 1996 the METC vacated the building and interior restoration work began. The building reopened in September 1997 with a fully restored interior and new Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) compliant rear conservatory entrance (Delaney 2012). Building surveys for these restoration efforts revealed a history of drainage issues in the building and a concerted effort was made to improve drainage. Unfortunately, problems have persisted. Damage on the basement level caused by Hurricane Irene made underlying issues readily apparent. As a result the METC has already undertaken a new building survey and developed a Preservation Plan in order to begin fundraising efforts for what is estimated to be a 2 million dollar, 10-year restoration project for the James Library. The METC greatly desires to preserve this architecturally and historically important building for future generations.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Peter Lee and the Museum of Early Trade and Crafts for their assistance.

References

Bloy, M. “Benjamin Disraeli (1804-1881).” n.d. The Victorian Web. www.victorianweb.org/history/pms/dizzy.html. Last accessed 20 September 2012.

Bulwer-Lytton, E. 2006. The coming race. (D. Seed, Ed.). Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Channing, W. H. 1899. The life of William Ellery Channing DD. Boston: American Unitarian Association.

Delaney, M. 2012. “Section 3: Building history and significance.” In Preservation plan- museum of early trades and crafts. Montclair, NJ: Krugman Associates Inc.

“D. Willis James dies in New Hampshire” 1907, September 14. The New York Times. Last accessed 20 September 2012.

Finkelstein, B. 1990. Perfecting childhood: Horace Mann and the origins of public education in the United States. Biography, 13(1), 6-20.

Grodzins, D. 2002. American heretic: Theodore Parker and transcendentalism. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

Hamilton, A.C. 1977. Sir Philip Sidney: a study of his life and work. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Howe, J. “Henry Hobson Richardson (1838-86).” 1998. The Digital Archive of American Architecture. http://www.bc.edu/bc_org/avp/cas/fnart/fa267/hhr.html.

“James library building details.” n.d. The Museum of Early Trades & Crafts. www.metc.org/details.htm. Last accessed 20 September 2012.

PHMC. “Beaux Arts Style 1885-1930.” 2013. Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/ late_19th_early_20th_century_revival_period/2390/ beaux_arts_style/294768.

Reeve, H. 1878. Petrarch. London: William Blackwood and Sons.

Wood, G. S. 2004. The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin. New York: Penguin Press.

Author Biography

Siobhan Fitzpatrick received her B.A. from Ramapo College of New Jersey and her M.A. in history from Villanova University. She has previously worked with the National Park Service and currently serves as the Curator of Collections and Exhibits for the Museum of Early Trades & Crafts in Madison, NJ.