Philadelphia Encapsulated: Popular

Prints and Photographs at the Library Company of Philadelphia

Erika Piola, Associate Curator, Library Company of Philadelphia

The Library Company of Philadelphia, the first successful subscription library in the country, was founded in 1731 by Benjamin Franklin and his Junto, a discussion group of mechanics, who sought to create a reference collection of books compiled from their own suggestions to aid in their scholarly debates.1 In the years following its inception, the Library Company also became a repository of art objects, artifacts, and graphic materials, often gifted by its supporters like nineteenth-century Philadelphia antiquarians Charles A. Poulson, and John McAllister Jr. and his son John A. McAllister. These prescient men collected visual materials that encapsulate the people, places, and events that embody the ethos of Victorian-era Philadelphia. They had the foresight to realize the future historical value of the stereographs, advertisements, and political cartoons that were viewed in the parlors, posted in the streets, and purchased in the print shops of their contemporaries. Collectors with a mission, Poulson and the McAllisters acquired several hundreds of these types of graphics, which were gifted to the Library Company in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The materials later served as the core collections in the formation of the Print and Photograph Department.2 This article aims to explore the significance of the department’s collection as a primary resource for the study of nineteenth-century Philadelphia as a physical and ideological place.3

The Print and Photograph Department4 is rich with graphics for the study of the built environment of nineteenth-century Philadelphia. Visual, material, and popular culture, are represented by the two revolutionary mediums of nineteenth-century mass image production; lithographs and photographs. Philadelphia served as a center of early development for each process. Bass Otis created the first successful American lithograph in the city in 1819 and local silver-plater Robert Cornelius was one of the country’s first daguerreans in 1839.5 Visual materials of this kind from which the library’s strong graphics holdings have grown are due to Poulson and the McAllisters.

Charles Augustus Poulson (1789-1866), a journalist, editor, and son of a Library Company librarian Zachariah Poulson, collected books, manuscripts, and visual materials, as well as created scrapbooks of newspaper clippings to preserve the cultural heritage of his life-long city of residence. Ever an eye to graphics, Poulson salvaged hundreds of antebellum-era lithographic advertisements depicting local businesses, as well as commissioned photographs of the changing architecture of the city. Bequeathed to the Library Company at his death in 1866, his collections, so significant today to the history of Philadelphia as a place, had already been realized as such by his peers. This was evident in his obituary, which noted “Very many localities in and about the city that would be entirely strange to the rising generations of Philadelphians have been drawn and painted at the private cost of Mr. Poulson in order to preserve, as far as possible, the early history and appearance of the city.”6 The McAllisters acted as kindred spirits, and the elder as a collaborator, in this pursuit.

The McAllisters descended from the Scotch émigré John McAllister Sr. (1724-1797) who had established a cane and whip manufactory in Philadelphia in 1781. In response to the burgeoning photography profession, by the mid-nineteenth century the family business had transformed into a successful opticians’ shop, McAllister & Brother. Original successor to the business John McAllister Jr. (1786-1877) focused on collecting printed and graphic materials about the history of Philadelphia and was a respected authority on the subject. His son John A. McAllister (1822-1896) anticipated the archival value of ephemera produced during the Civil War, a watershed moment in the cultural history of the United States. In 1886 these materials that symbolize the intertwined business and personal lives of the McAllister men became a permanent part of the collections of the Library Company when accepted from John A. McAllister by the library’s Board of Directors.7

John McAllister Jr. was an early proponent of photography. The family’s opticians’ shop was one of the earliest to carry camera lenses, and in 1840, John Jr. was the first to sit for a portrait at the studio of the aforementioned Robert Cornelius.8 The daguerreotype process, the first widespread practical method to create photographs invented by Jean-Louis Daguerre in 1839, produced one-of-a kind images developed on highly polished, sensitized plates. The daguerreotype contemporarily touted as the truest form of reproduction, a “recreation of nature,” started the impending debate for years to follow about whether photography was art or photojournalism.9

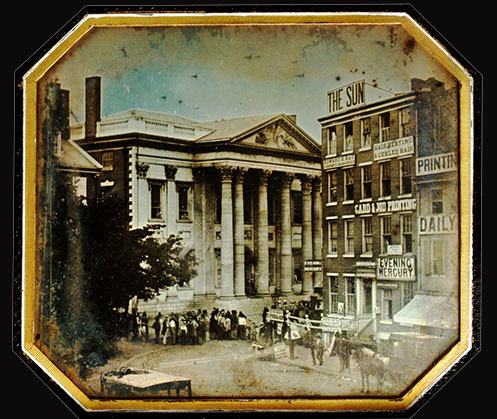

Before his death in 1896, John A. McAllister gave the library a daguerreotype of the Girard Bank by American pioneer photographers the Langenheims. The brothers William and Frederick, former journalists, operated one of the first daguerreotype studios in the city, serendipitously across the street from the financial institution (Figure 1).10 One of the earliest news photographs taken in the country, it shows the bank during the notorious Nativist Riots of May 1844.

Figure 1. William and Frederick Langenheim, North-East Corner of Third & Dock Street. Girard Bank, at the Time the Latter was Occupied by the Military During the Riots, May 9, 1844. Daguerreotype. Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

The anti-Catholic Riots represent an ugly moment in the history of the city founded on religious freedom. The deadly and destructive uprisings, begun from a rally of the American Nativist Party in the predominately Irish-Catholic neighborhood of Kensington, were squelched after the Pennsylvania militia was called to the city following a declaration of martial law by mayor John Morin Scott. The Girard Bank as documented in the scene served as the headquarters of the militia.11

The Langenheims captured the view through the use of a prism over the camera lens to prevent a reversal of the image – the natural outcome of daguerreotypy. The daguerreans, as past newspapermen, wisely understood the intrinsic appeal of a “real” view of the event would be lost if the spectator was distracted by visual inconsistencies. The context; the content, that of a view as opposed to a portrait; and the photographers of this image make it a treasure of the graphics collections. One of the earliest photographic pieces in the department showing the built environment of Philadelphia, its medium, subject matter, and provenance evokes questions about its role in understanding nineteenth-century popular meanings of photography that the McAllisters and now the Library Company preserves for future researchers. While the possession of the Langeheim daguerreotype conceivably stemmed from the unmitigated antiquarianism of the McAllisters, their large collection of stereographs given to the library certainly represents the McAllisters access to modes of popular material culture through their profession.

Stereographs, a quintessential form of nineteenth-century parlor entertainment, form one of the larger segments of the Print Department’s photographic collections.12 An interactive visual medium, stereographs were composed of a double-sided photograph mounted on card stock that when viewed with an instrument known as a stereoviewer created a three-dimensional image. The photographs, issued by the major firms in the 100,000s per year by the 1860s, provided nineteenth-century viewers with a venue to learn about their own local haunts as much as about foreign places, and are a primary resource for modern-day researchers of cityscapes, popular culture, and visual history.

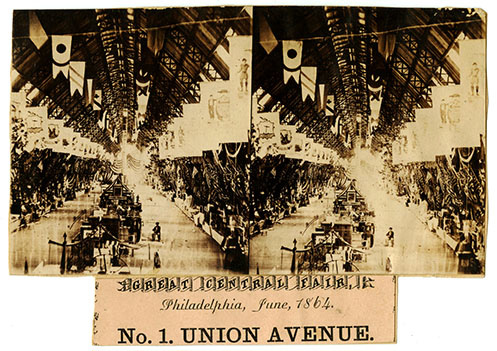

The McAllister family firm, as an opticians’ shop, was a major purveyor of stereographs in Philadelphia. An interesting set of stereographs distributed by the firm symbolizing an intersection of a medium and its content representing popular and material culture, as well as intentionally ephemeral Philadelphia architecture are a series of photographs published by William Langenheim of the Great Central or Sanitary Fair, the Civil War fundraiser in Philadelphia.

The event held June 7-28, 1864 on Logan Square, now Circle, was one of a number of national fairs that displayed art, craft, and historical exhibits to benefit the soldier relief organization the U.S. Sanitary Commission. The photographs portray major exhibits like the Horticultural Department, the Relics and Curiosities Department, and the Penn Parlor, which contained William Penn memorabilia and antiquities. The views also saved for posterity an idea of the smaller exhibits, donated prizes, and award-winning machinery, much of which lined Union Avenue, the heavily decorated arched central thoroughfare of the fair. Described by a member of the fair committee as “impossible to imagine anything more imposing in its effect…singularly novel and picturesque…festooned at its apex with green boughs hung lower down with banners and trophies..., as in some great baronial hall of the middle ages,” the stereographs attest it “made up a dazzling picture such as no eye had ever looked upon on this continent” (Figure 2).13

Figure 2. A. Watson, No. 1 Union Avenue (Philadelphia: American Stereoscopic Company, 1864). Albumen on stereograph mount. Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia. View this image larger.

About 250,000 people, a number equal to about 1/3 of the city’s population bought tickets to the fair that also included a restaurant, receiving area for donations, and conveniences, including public restrooms and ladies’ changing areas. Visitors often frequented the benefit several times per week, or even per day. The Langeheim stereographs allowed individuals to partake in the monumental Philadelphia event from their parlor if they were unable to be a part of it in person. The series also allowed fair visitors to relive the experience, purchase the views as souvenirs, and/or feel like the possession of the photographs contributed to the patriotic cause.

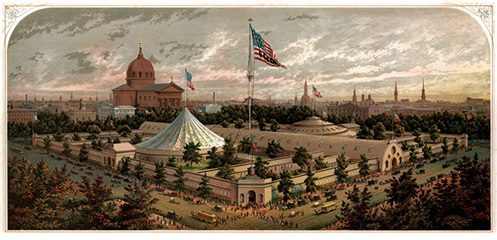

Needing a larger than existing structure in which to house the exhibits, volunteer craftsmen completed a temporary complex on Logan Square. The public space was chosen by fair organizers because its “broad walks…had been so laid out that they could all be occupied with suitable buildings, properly in communication with each other.” Additionally, the trees in “full foliage deprived the fair of that barrack-like effect” that such structures would have possessed in their “unadorned ugliness.”14 In only forty days the artisans created a 200,000 square foot complex with central thoroughfare after the designs of Henry E. Wrigley and Strickland Kneass. Boasted as the “grandest ever erected on this continent for any similar purpose,” the temporary structure thankfully found a life in perpetuity through not only stereographs, but a chromolithograph of the exterior (Figure 3). The print proves significant for another reason. The graphic plays a critical role in the visual history of the city. It is a harbinger of the rise in production of chromolithographs, that is color printed lithographs, as a desirable medium for popular art.

Figure 3. James Queen, Buildings of the Great Central Fair, in Aid of the U. S. Sanitary Commission Logan Square, Philadelphia, June 1864 (Philadelphia: P. S. Duval, 1864). Chromolithograph. Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia. View this image larger.

Chromolithography was still perceived as a novel, imperfect art form in America at the start of the Civil War. Unfavorable comparisons with European works had slowed consumer acceptance of frameable, American-made chromolithographs. This chromolithograph promoted a new level of interest in Philadelphia for the printing process when demonstrated on the central promenade at the fair. Reported in the fair’s daily publication as attracting “the attention of every visitor,” the view printed in nine colors was made available for sale daily by the renowned Philadelphia lithographic printer P. S. Duval (1804/5-1886). Designed by James F. Queen (1820/1-1886), one of the most respected, versatile, and prolific lithographers of the era, the souvenir print showing the site of its production could be had by visitors for $2 with the proceeds given to the Sanitary Commission.15 Such funds helped the fair raise over $1,000,000 for the organization, whose member’s work is reflected in the Langenheim stereographs.

After retirement from the family business, John Jr. focused his energies on his antiquarian interests. Acquiring photographs of the changing cityscape of mid-nineteenth century Philadelphia encompassed part of this pursuit. The elder McAllister’s friend and fellow antiquarian Charles A. Poulson helped to provide the means when he commissioned Philadelphia artist and photographer Frederick De Bourg Richards (1822-1903) to photograph the vanishing and transforming architectural landscape of Philadelphia. Between circa 1855 and 1862, Richards produced over 100 of some of the earliest extant paper photographs of Philadelphia streetscapes that document public, commercial, and residential buildings. The views depict reallocated buildings such as the “Military Hall” on the 400 block of Library Street near Chestnut Street (Figure 4). The former arsenal building built as a print shop in 1810, is captured in its current life as a lager beer hall operated by prominent local brewer Gustavus Bergner. The photographs also show the construction of the Continental, a “modern” luxury hotel, built on the former site of a theatre building in 1858 and the Jayne Building, a harbinger of the skyscrapers to come, in about 1859 (Figure 5). Completed in 1850 for patent medicine mogul David Jayne, and expanded in 1851, the towering structure was then known as the most extensive and expensive private building constructed in any city in the country. It was razed in 1957.

Figure 4. Frederick De Bourg Richards, Library Street, Southside, Between Goldsmith’s Hall and Fourth Street, ca. 1859. Salted paper print. Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

Figure 5. Frederick De Bourg Richards, Jayne Building, 240-242 Chestnut Street, ca. 1859. Albumen print. Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia. Originally built 1848-50 after the designs of architect William J. Johnston, the building was expanded in 1851 after the designs of Thomas. U. Walter.

Created as records of disappearing and emergent architecture, the ancillary and incidental aspects – signage, street traffic, playbills – also provide a window into the experiences of the city residents as pedestrians, consumers, and citizens as they walked the city streets. The images evoke the physical and cultural atmosphere of the city of the 1850s and represent eighteenth-century architecture redesigned and repurposed to accommodate the new needs of nineteenth-century Philadelphians. The views commemorate the past as well as tacitly acknowledge the necessity of change to keep a city vital through developments such as the erection of a fashionable hotel and the re-appropriation of a structure to prevent its obsolescence.

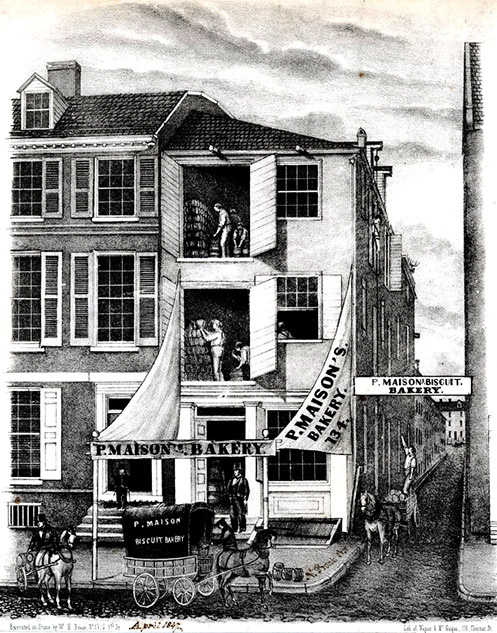

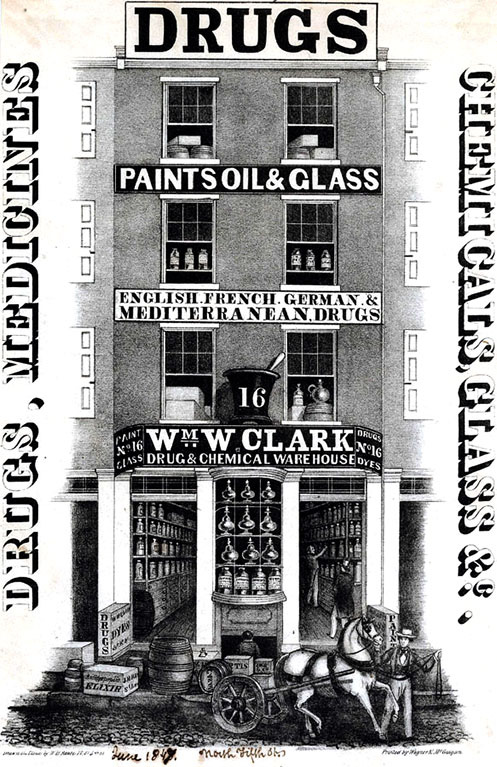

The prints and photographs collection also contains a variety of formats of printed nineteenth-century advertisements symbolizing the marketing methods of that era. Plates removed from city directories, trade cards, and advertising circulars all enhance the collection to learn about the urban landscape. The increasingly diverse methods for advertising went hand in hand with the urban development. Poulson, in line with his commissioned series of photographs, salvaged near 100 different lithographic advertising prints between the late 1830s and 1850s. These depicted the facades of a wide-range of Philadelphia businesses and manufactories, ranging from bakeries, dry goods stores, cabinet makers, and hotels, to iron foundries and a match manufactory (Figure 6). Often dated and the addresses occasionally plotted by Poulson on the prints, the lithographs tend to include partial views of adjoining properties, and portray a design composition with regard to the façades that appears particular to Philadelphia lithographs.

Figure 6. William H. Rease, P. Maison’s Biscuit Bakery (Philadelphia: Wagner & McGuigan, 1847). Lithograph.

Lithography, the flat-surface printing process invented in Europe circa 1798, transformed American printing in the 1820s. More efficient and allowing more versatility in design and in larger sizes, the process helped to spur the production of large format views of urban centers like Philadelphia. The Print Department holds a number of Philadelphia cityscape lithographs in its collections, of which the Poulson advertisements form a significant part.16

While produced as advertisements, the prints also provide both a micro and macro vision of Philadelphia cityscape at the dawn of its notoriety as the workshop of the world. Analyzed in detail through photographs and contemporary written descriptions from the period by urban historian Dell Upton, the prints, as astutely concluded by the author, are simultaneously accurate and misleading when viewed from a more concentrated perspective.17 Although Upton focuses more on the accuracy of the architectural details in his overall analysis, the effusive signage portrayed provides the analytical focus for this author (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Wm. W. Clark, Drug & Chemical Warehouse (Philadelphia: Wagner & McGuigan, 1847). Lithograph. Note Poulson’s inscription in the lower margin.

Although seeming anachronistic for that era, the breadth of signs adorning the buildings was not added for affect, but actually pervaded the commercial cityscape. The profundity of such advertising had hit such a level that the local paper Evening Bulletin devoted a three-column article to the “problem” in 1857.18 Described as garish, in bad taste, and in “contempt of orthography,” the signs, according to the argument of the newspaper, produced a sensory overload that caused the spectator to become blind to the advertising. The crux of the article; newspaper advertising that circulated widely and that was not stationery best served the marketing goals of store proprietors. It is a case of antebellum mass media competition. However, these lithographic advertisements prove a foil for the Bulletin’s self-serving position of the supremacy of newspaper advertising. These prints posted in lobbies, rail cars, and shop fronts also circulated, and often to wholesalers in other parts of the country.19 The lithographs certainly facilitated a more direct marketing approach. A possible patron did not need to wade through columns of promotion to learn about a business when your store provided the main focus of the image, with ironically, the chastised signage often serving as the most eye-catching advertising text.

The prints also engage the modern-day viewer for their intentionally portrayed glimpses of interiors visible through open entryways and shop windows crammed with merchandise displays. Clerks with patrons, shelves of inventories, and the shop’s manual laborers on the job more often than not were included as pictorial details that added to the aesthetic of a prosperous business. Foot and street traffic comprised of draymen, patrons, and pedestrians also served to signify the increasing importance of a society of consumers. Although a blatant marketing device, these not so incidental portrayals prove even less incidental as primary visual evidence for the cultural scholar of Philadelphia. Crates marked with their destination document the national market for Philadelphia goods; drays and wagons demonstrate the vital role of nineteenth-century horsepower; and the oft-depicted pedestrian and street congestion not yet able to be reproduced photographically allude to the city’s demographics.

To further elucidate this question of accuracy in these graphics, the shadowy partial views of adjoining buildings in many of these advertisements must be addressed. The details serve a purpose in understanding how the larger picture of the city becomes subsumed through such focused imagery, particularly from the 1850s. As noted by Upton in his conclusion to his essay, the visual trope belies the nascent skyscrapers emerging at mid-century, as portrayed in the Richard’s photograph of the Jayne Building (see Figure 5), that are dwarfing the repurposed buildings that deceptively appear so prominent in the prints. In addition, the peripheral details in the graphics imply that placing a series of the views side by side would in theory recreate an entire block. Unfortunately, such a “panorama” cannot yet be realized. As is the nature of extant historical graphics, it is unclear if individual prints of every building on a commercial block ever existed or just did not survive. Perhaps, the partial views were for pure artistic affect or to entice the minimally featured shop owner to also commission a print, or possibly the peripheral depiction signified that the shop proprietor paid a small commission to be alluded to in the advertisement. A visual scholar must often walk this fine line of conjecture to best interpret the conceptual contexts of the images and the prescriptive intentions of their makers.

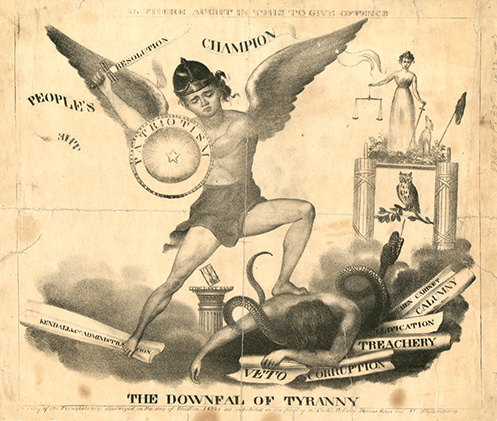

Images that portray Philadelphia as an ideological, as opposed to a physical space, also form the collection, particularly through political cartoons. Usually printed by lithography by the 1830s, cartoons are the epitome of popular culture due to their immediateness in production and contemporaneousness in comprehension. Sold in the hundreds, and sometimes thousands, by print shops and often circulated at coffee houses and taverns or displayed at workshops, these satiric graphics reflect the fashion of the times, aesthetically, politically, and socially.20 The department holds hundreds of cartoons, ranging in date from the early eighteenth century to the early twentieth century, with a large cluster parodying Democratic president Andrew Jackson and his administration during the early 1830s. One of the most atypically delineated cartoons held by the department comes from this cache. Titled The Downfall of Tyranny, the 1832 satire lambastes the autocratic policies and the re-election of Jackson (Figure 8). What makes the cartoon so atypical is that it is in essence a facsimile of a transparency that adorned the hotel of Samuel Carll, the Whig headquarters in Philadelphia during the election. Using an ironic visual trope based on the Coat of Arms of Virginia, the cartoon is not only an historical artifact of political sentiment, but also the city’s built environment and visual culture during the 1830s. While most cartoons do not embody such a triality, this one is highlighted to make the point that historic graphics must be conceived of in their whole context if not to be unintentionally underestimated and underutilized as historic primary evidence.

Figure 8. The Downfall of Tyranny (Philadelphia, 1832). Lithograph. View this image larger.

Mass-produced, marketed, and circulated, visual materials available to all classes of people with all levels of education and wealth provide a means to understand the society that produced, viewed, and incorporated the graphics into their lives, as well as the images’ messages into their collective and individual consciences. The mass availability and production of graphic works propelled by photography and lithography during Poulson’s and the McAllisters’ lifetime created a more modern visually literate society whose culture contemporary scholars continue to research. The Print and Photograph Department at the Library Company contains the visual materials, from the mundane to the sensational held, seen, and contemplated in the daily existences of Philadelphians of the Victorian era. Through collectors like the McAllisters and Poulson, and institutions like the Library Company, we are fortunate that the visual culture of the Philadelphia of yesteryear remains in constant dialogue with the visual culture of the city of today.

Endnotes

1 In the mid-twentieth century the library transformed into a closed-stack research facility to provide the best access to its nationally and locally significant collections of books, prints, manuscripts, and ephemera strong in not only the research of Philadelphiana, but Americana, including African American history, Women’s history, economics, and natural history.

2 In 1971 the separate Print Department was conceived with the majority of its core collections comprised of the Poulson and McAllister collections of graphic materials. Over the last decade, grant-funded projects and the initiation of a Visual Culture Program (http://www.librarycompany.org/ visualculture/index.htm) have enabled greater focus on the research and interpretation, as well as online accessibility of the library’s visual materials collections, which include near 100,000 items in the Print and Photograph Department.

3 An earlier version of this paper was presented at “Material Culture: Museums and Libraries,” Session 8 of the 44th Annual Conference of the Pioneer America Society: Association for the Preservation of Artifacts and Landscapes, September 28, 2012.

4 Although officially titled the Print and Photograph Department, the department is colloquially referred to as the Print Department and will be often referenced as such in this essay.

5 See “Lithography,” American Journal of Science 1, no. 4 (1819): 439 and William F. Stapp, Robert Cornelius: Portraits from the Dawn of Photography (Washington, D.C.: Published for the National Portrait Gallery by the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1983).

6 Commercial Lists, March 24, 1866.

7 For a concise history about the provenance and the library’s acquisition of the collection, see Sandra Markham, “John A. McAllister Collects the Civil War,” The Magazines Antique (August 2006): 102-137.

8 Sara Day, ed., Gathering History: The Marion Carson Collection of Americana (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1999), 102.

9 Several texts have been published addressing the cultural role of early American photography. Recent volumes analyzing the historical debates about the mimetic nature of photography include Marcy Dinus, The Camera and The Press: American Visual and Print Culture in the Age of the Daguerreotype (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012); Miles Orvell, American Photography (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003); and Alan Trachtenberg, Reading American Photographs: Images as History Mathew Brady to Walker Evans (New York: Hill & Wang, 1989).

10 William Brey, “The Langenheims of Philadelphia,” Stereo World 6, no. 1 (March –April 1979): 4-20 and Ellen NicKenzie Lawson, “Fathers of Modern Photography,” Pennsylvania Heritage (Fall 1987): 16-23 document the central role of the Langenheims in the introduction of early photographic processes to the United States.

11 For a contemporary account of the riots, see A Full and Complete Account of the Late Awful Riots in Philadelphia (Philadelphia: John B. Perry, No. 198 Market Street., 1844).

12 See Laura Schiavo, “A Collection of Endless Extent and Beauty: Stereographs, Vision, Taste and the American Middle Class, 1850-1880” (Ph.D. diss., The George Washington University, 2003) for a recent comprehensive history of the production, distribution, and consumption of stereographs.

13 Charles J. Stille, Memorial of the Great Central Fair for the U.S. Sanitary Commission Held at Philadelphia June 1864 (Philadelphia: United States Sanitary Commission, 1864), 33.

14 Ibid, 21.

15 Our Daily Fare, no. 11, June 20, 1864.

16 In 2007 the Library Company of Philadelphia embarked on Philadelphia on Stone, a three-year collaborative project that examined the first fifty years of commercial lithography in Philadelphia, 1828-1878. The project culminated in a digital catalog, an online biographical dictionary of lithographers, an exhibition, and an illustrated volume of thematic essays of the same title published in 2012. The Philadelphia on Stone online collection can be accessed at www.lcpdigital.org.

17 Erika Piola, ed., Philadelphia on Stone: Commercial Lithography in Philadelphia 1828-1878 (University Park, PA : Pennsylvania State University Press in association with the Library Company of Philadelphia, 2012), chap. 6.

18 Evening Bulletin, April 25, 1897. Newspaper clipping in Poulson scrapbooks, Illustrations of Philadelphia, volume 9, p. 41 in the collections of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

19 Jennifer Ambrose, “Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia Advertising Prints,” in “The Library Company of Philadelphia,” special issue, Antiques, 170, no. 2 (August 2006): 96.

20 For the most recent, thorough account of the early history of American political cartoons, see Allison Stagg, “The Art of Wit: Political Caricature in the United States 1780-1830” (Ph.D. diss., The University of London , 2011). See also the classic history, William Murrell, A History of American Graphic Humor, vols. 1-2 (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1933).

Author Biography

Erika Piola, Associate Curator of the Prints and Photographs Department has worked at the Library Company since 1997. She recently served as editor of Philadelphia of Stone: Commercial Lithography in Philadelphia 1828-1878 and is Co-Director of the library’s visual culture program VCP at LCP.