Following Grandpa’s Footsteps: Retracing The Indian Paths of Pennsylvania

Edie Wallace

“May your moccasins always be dry, your path free from logs and briars, and may the sun shine long in your lodge.”

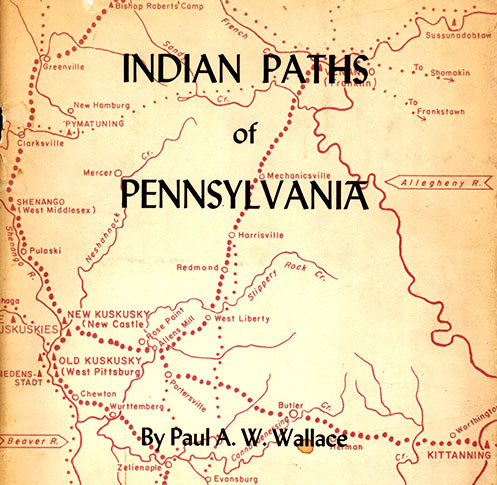

In 1949, my grandfather, Paul Anthony Wilson Wallace, began a 16-year journey to identify and trace the Indian paths of Pennsylvania. A professor of English literature at Lebanon Valley College, Dr. Paul A. W. Wallace was already the author of several books, including one on the Iroquois Confederacy, The White Roots of Peace (1946), and one on the historic contacts between whites and Indians in the region, Conrad Weiser Friend of Colonist & Mohawk (1945). He was an accomplished researcher and writer and his deep appreciation of American Indian history and culture made him perhaps the most obvious candidate for the project, sponsored by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. The result, The Indian Paths of Pennsylvania, traced the routes of 131 paths across every county in Pennsylvania and formed the basis for the ubiquitous blue and yellow metal historic signs we see along the roads across Pennsylvania today (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Indian Paths of Pennsylvania traced the routes of 131 paths across every county in Pennsylvania and formed the basis for the ubiquitous blue and yellow metal historic signs seen along the roads across Pennsylvania today.

The many Indian paths that crossed and re-crossed the mountains and valleys of Pennsylvania at the time of European contact and colonization were not well-developed roads. “The Indians of Pennsylvania,” notes Grandpa Wallace, “…built no roads like those of the Inca, whose wide stone highways spanned gorges with suspension bridges, traversed high mountains, and ran through galleries cut out of solid rock to fend off avalanches.” Still, he observed, “Our Indian paths were good of their kind, good for the uses to which they were put and for which they were intended: the moving about of moccasined men and women.”

The First Americans who occupied the land that would become “Penn’s Woods” were a loosely organized group known as the Lenni Lenape (Delawares), within the “empire” of the Iroquois Six Nations. Pennsylvania Indian paths moved hunters to their hunting grounds, were routes of trade, warrior’s paths, or avenues of peace, such as the Iroquois “Ambassadors Road.”

That they were well laid out is attested by the fact that, even in the broken mountain country of this Commonwealth, where the road problem is complicated by countless springs from the hills, the Indian paths served the white man’s needs for a hundred or more years after his arrival… (p. 2)

In a letter to William Penn, written in 1758, General John Forbes wrote that the Indians “have foot paths…through these desearts [sic], by the help of which we make our roads.” (as cited, p. 2)

Up through the early twentieth century, until the automobile changed the way we use roads, observed Grandpa, many routes still largely followed the Indian paths along the “dry, level, and direct” river terraces “above flood level” or the “modest elevations in the midst of wide valleys overlooked by the mountains.” As population pressures moved the Indians ever westward, paths evolved:

Trails were widened into bridle paths for the traders’ pack trains. By the time of the Revolution, bridle paths had been converted into wagon roads as far west as Pittsburgh. After the Revolution the movement continued, converting wagon roads into railroads west “to the setting sun” and the Western Sea. (p. 11)

And of course, many wagon roads evolved into early turnpikes and later highways, while many continued in use, relatively unchanged, as county routes.

“In Pennsylvania today,” wrote Grandpa in the early 1960s, “it is seldom possible to walk an old Indian path.”

Most traces have been obliterated by farming, lumbering, road making (whether wagon road or railroad), house building, and strip mining…

Nevertheless it is possible to map the old paths with a fair approach to precision. There are many sources of information available, many kinds of evidence which can be used as guides.

Since the Indians themselves did not leave written records of their pathways, Grandpa’s research relied on early maps, travel journals, letters, land warrants and surveys, noting “The Bureau of Land Records at Harrisburg is the pathfinder’s paradise.” (p. 11) More modern sources included road viewer reports and archaeological reports. Significantly, because Grandpa’s research was taking place around 1950, he was able to interview older road workers, whose memories of alterations to routes, particularly in the 1930s were key to identifying historic routes.

My own journey as an historian in Maryland can be traced back to my roots in Pennsylvania, and my father’s career as an historian with the National Park Service at Independence Hall. I was equally inspired by Grandpa’s studies of Indian culture, my grandmother’s love of archaeology, and my uncle’s tenure as an anthropologist at the University of Pennsylvania. I come by it honestly. My personal fascination with old maps and historic roads came in handy recently when I was tasked with the job of tracing the route of the ‘Great Waggon Road to Philadelphia’ as it passed through Maryland and across the Potomac River at Packhorse Ford into Virginia. From there the road followed the Shenandoah Valley south to the Cumberland Gap in Kentucky. Roads lead us along the paths of our history – to the hunting ground or trading post, to the mill, church, or courthouse, or to the western frontier.

I chose to retrace my Grandpa’s footsteps along just one of the 131 paths he researched for his book –The Minquas Path from Wrightsville to Fort Manayunk (now the Philadelphia Airport), following the routes he suggested with the patient and enthusiastic help of my driver/husband. How much had the modern routes changed since the 1965 publication of my Grandpa’s book? Could we still sense the reasoning of the Indian route? And how did that path tie into the ‘Great Waggon Road to Philadelphia’ that crossed into Maryland and forded the Potomac River just outside my front door? And who doesn’t “love any book that opens to a map”? (Wayne Brew, personal communication)

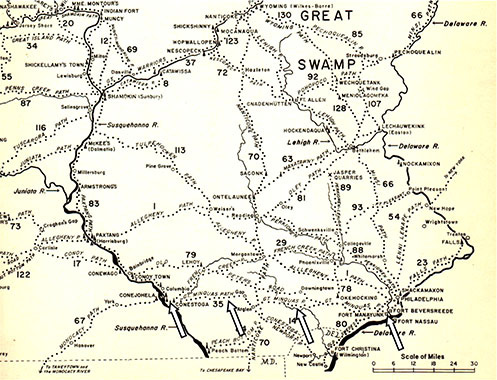

Figure 2. “Key to the Indian Paths of Pennsylvania,” large map inside the book cover showing the 131 paths followed in the book. This detail shows (white arrows) the Minquas Path. View this image larger.

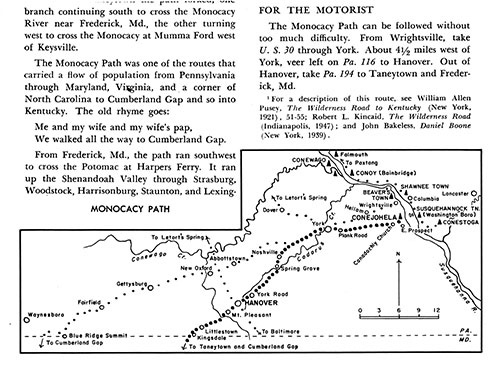

But first we had to find a route from our home on the Potomac River in western Maryland to the Susquehanna. Back to Grandpa’s book (Figure 2). The Monocacy Path conveniently (for us) came out of Maryland at Taneytown leading to the west bank of the Susquehanna River at Wrightsville, directly connecting Maryland to the Minquas Path (Figure 3). The Monocacy Path, an Indian path followed in the 1720s and 30s by settlers heading for the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, was a branch of what became known as ‘The Great Waggon Road to Philadelphia.” The road crossed the Potomac River at Packhorse Ford, less than a half mile from my front door (Figure 4). My recent research for a National Register nomination of the Packhorse Ford and nearby cement mill provided a unique connection with my grandfather’s research.

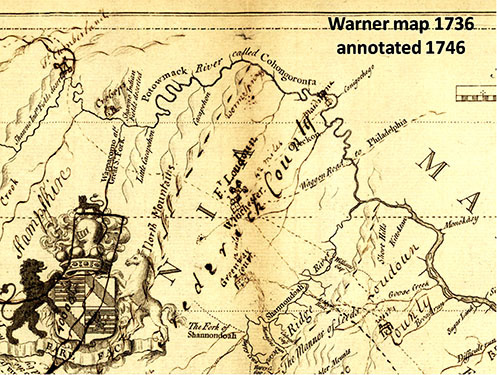

Figure 3. 1736 “Survey of the northern neck of Virginia” by John Warner, annotated in 1747 (Library of Congress).

Figure 4. The Packhorse Ford of the Potomac River, Maryland side looking toward West Virginia (EBW 2012).

Our route led us across Antietam Creek at the Antietam Iron Works, over South Mountain at Crampton’s Gap, and northeast through Frederick and Carroll Counties, through Taneytown to the Mason-Dixon line. In Pennsylvania we continued to New Oxford, along Route 30 through York (Figure 5). Approaching the river we hit traffic stopped dead at the bridge so we turned off onto the older Lincoln Hwy bridge to Columbia and turning right along the bank of the Susquehanna River, began to follow the Great Minquas Path – as identified by my grandpa (and Google maps!) (Figure 6).

Figure 5. “Monocacy Path” (Wallace, p. 105). View this image larger.

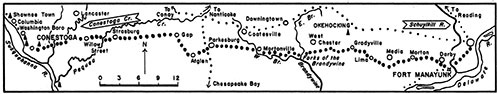

Figure 6. Detail map of the Great Minquas Path (Wallace, p. 65). View this image larger.

Over this path the Susquehannock Indians yearly brought great wealth in beaver skins to the eastern trading posts. The Minquas Path not only laid foundations for Pennsylvania’s commercial development. It also provides a key to much of the Commonwealth’s early history. “The struggle by Holland, Sweden, and Great Britain for the possession of the Delaware River,” writes George P. Donehoo, “was in order to control the trade with the Minquas living on the Susquehanna.” (Wallace, p. 64)

The Minquas or Conestoga Indians were the “last of the once mighty Susquehannocks” who lived in small settlements along the Conestoga Creek. Their trading pathway followed the creek from the Susquehanna River, crossing higher ground to the Brandywine Creek. The county road we followed along the Brandywine was indeed little more than a foot path (Figure 7), at times sharing the dry ground above the creek with a railroad line (Figure 8).

Figure 7. Mortonville Road along Brandywine Creek, just east of the Susquehanna River (EBW 2012).

Figure 8. Road and rail along Brandywine Creek (EBW 2012).

From Columbia to West Chester our route was rural, passing through historic farmland and following routes little changed from their historic path. Then we came into Swarthmore. With that the joy of the journey, now 6 hours later, was gone. Though a lovely town, the surrounding mess of roads and houses and commercial strips were too much. We never made it to Fort Manayunk (now the Philadelphia International Airport). Our 6 hour journey there was a mere 2 1/2 hour drive home on Interstate 95, likely a several days journey by foot or horse. Remarkably for much of the journey we could clearly sense the original path.

The Indian Paths of Pennsylvania is a remarkable resource for anyone doing research in and around Pennsylvania, still as relevant today as it was 50 years ago when my Grandfather was stalking the roads and records. Grandfather Wallace wrote that he hoped that “other students of outdoor history may find this work helpful in building a still closer knowledge of our Indian heritage.” It is my hope that other researchers will pull the book off the shelf, blow off the dust, open it to that awesome map, and reacquaint themselves with The Indian Paths of Pennsylvania.

Author Biography

Edie Wallace is the granddaughter of Paul A. W. Wallace. She continues the family vocation as historian with the cultural resources consulting firm of Paula S. Reed & Associates in Hagerstown, Maryland.