The Bethel Colony: Intersections of Culture and Built Form

Janet R. White

The town of Bethel, once the site of the Bethel Colony, sits on a gentle slope rising from the bank of the North River in Shelby County, Missouri, about 45 miles west of Hannibal. In the fall of 1844 a group of colonists of Germanic origin, led by Dr. William Keil, arrived at what was to become their new home. They found a tree-lined creek, an Indian trading post, a small gristmill, and a few scattered farms set in a seemingly endless vista of rolling prairie grass. One year later a town had been laid out, houses were being added as fast as they could be built, and construction of a large, new, steam-powered gristmill was underway.

The Bethel Colonists were Bible communists: land, buildings, and means of production were held in common. They found the inspiration for their communal life in the Bible, specifically in the Book of Acts, which records that in the early church “as many as were possessors of lands or houses sold them and brought the proceeds and laid them at the apostles’ feet; and distribution was made to each as any had need” (RSV, Acts 4:34-35). Communal ownership at Bethel applied only to “lands and houses,” or in modern economic terms, real property and means of production, and not as in some of its contemporary utopias to such items as clothing. The Colony functioned on this communal basis for thirty-seven years, until the death of Dr. Keil and decreasing commitment to the communal ideal led to the assets of the community being divided among its members in 1881.

The focus of this paper is on the intersection of the economic structure of the Colony with the built form it produced over the course of its existence; specifically, it focuses on how the unique aspects of their way of life influenced their architecture and site planning. At least twenty of the buildings constructed by the Bethel Colony in and around the town of Bethel are extant, though some are in poor condition and others have been significantly altered. Parts of the town look today much as they did in Colony times, and the street pattern has not been changed since it was laid out by the colonists. In addition to the primary settlement at Bethel, the Bethel Colony built three groups of houses in the immediate vicinity to which were given the names Elam, Mamri, and Hebron, and they founded a branch settlement called Nineveh in adjoining Adair County.

The economic structure of the community was unusual among 19th-century communal utopias in that the members were permitted small private incomes. These were earned by selling items of individual production, such as surplus vegetables from household gardens, at a community store where non-members from the surrounding areas were welcome cash customers. Both the architecture and the site planning of the Bethel Colony exhibited this same unusual mix of the collective and the private. Communalism at the large scale of the community was combined with variation, choice, and room for initiative at the individual level.

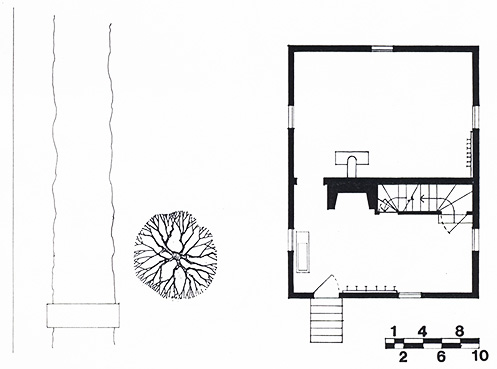

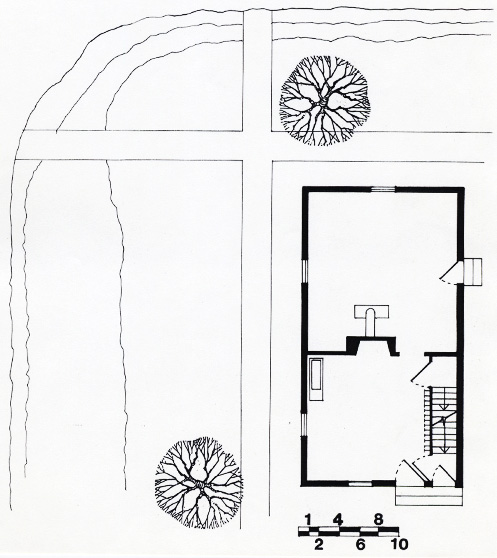

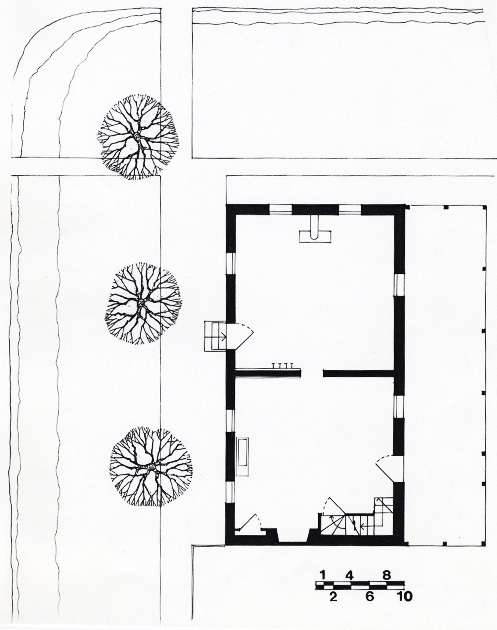

This combination of large-scale communalism and individual-level variety can be seen in a comparison of three of the houses built at Bethel. All three houses were measured by the author; the plans in Figures 3 to 5 were developed from these measurements.

Figure 1. Bair House (photo by author)

Figure 2. Zeigler House (photo by author)

The first two are the Bair House, the first house to be built by the Colony, and the Zeigler House (Figures 1-2). At first glance they look very similar, and in many ways they are. Both are two story structures clad in clapboard. The windows and doors are exactly the same size, suggesting that they were produced in a common workshop; the windows of all the Bethel buildings were 2’5” wide. The earlier windows are two panes over two; later they began to use six over six or even nine over six, but all within the same frame size. In plan, both houses have two rooms on the ground floor with a central fireplace (Figures 3-4). This was the standard plan for a typical Bethel Colony house.

Figure 3. Plan of Bair House (drawn by author)

Figure 4. Plan of Zeigler House (drawn by author)

Much of the construction done at the Colony in the earlier years used the fachwerk technique typical of German vernacular architecture of the era, a construction method in which heavy, hand-hewn, timber framing creates a rigid box of structure and the spaces between the timbers are filled in with nogging material. At Bethel, this material was usually hand-made brick baked in one of several wood-fired kilns scattered throughout the community (Bower 1972).

Originally the exterior timber and brick work was stuccoed, but the harsh Missouri winters soon led the Colonists to add a layer of lapped horizontal wood siding for additional insulation.

The inside of the houses was generally plastered, so that little visual evidence of the fachwerk remained.

The Miller House was built in 1855, ten years after the Bair House (Figure 5). By this time, the Colony was building in thicker brick walls, without the clapboard, but the window sizes remain the same, as does the basic two over two floor plan.

Figure 5. Plan of Miller House (drawn by author)

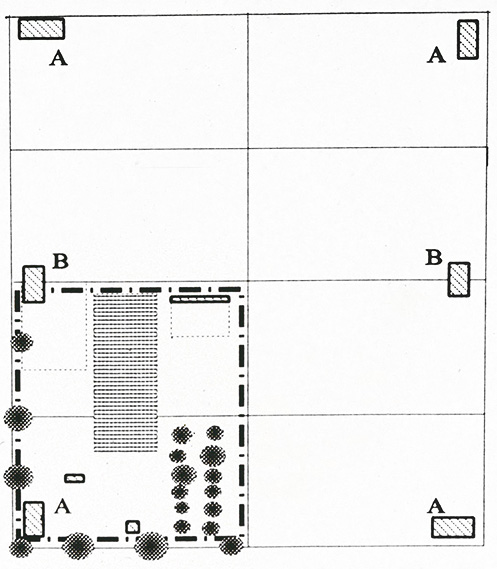

Figure 6. Plan diagram of typical Bethel block (drawn by author). A = Single family house. B+ Shard barn.— • — • — = Home side consisting of two lots.

Though the three houses are similar in all of these ways – basic floor plan, window size, etc. – they are not identical. They are not exactly the same size in plan or exactly the same shape. The location of the door is different, as is the location of the stair. Furthermore, the Zeigler and Miller Houses are a full two stories, while the Bair House is really one and a half, although it has second story windows. In the Miller House, built later than the first two, the chimney is moved from its central location and a stove is incorporated into the second room on the first floor. In other words, in their architecture we see a fundamentally communal environment within which individualism in detail occurs – the same pattern as in their economic structure.

Unlike many 19th c utopias, such as its contemporaries at Oneida and Bishop Hill Colonies, at Bethel Colony the utopian vision did not challenge the primacy of the nuclear family. The nature of the family and its relationship to the collective at Bethel appear at first glance to differ only slightly from the cultural norm -- the norm in mid-19th century America still being a nuclear family with a large number of children who live in a single family house which, in the 1850’s, was most likely to be located on a farm. The Colony was organized by nuclear families, each family housed separately. The makeup of the individual households varied, but examination of the detailed U.S. Census records for 1850 and 1860 reveals that the typical Bethel house was occupied by a husband and wife, their children, and one to four additional individuals. While there was a communal living space, the Grossehaus, the Census data reveal that those who lived in the Grossehaus were almost all individuals who did not have nuclear family ties in the Colony. Moreover, the Census data show that a number of such unrelated individuals lived in the houses of – and one assumes shared the life of – one of the nuclear families, much as a hired hand or hired girl might in a typical American farm household of the time. So at Bethel Colony, the individual family in the single family house remained the locus of domesticity.

The difference in site planning that does not strike one immediately between the Bethel house and the house of the typical American household of the time is that the Bethel house is no longer located on a farm; it is set on the street of a town. The fields and barns of Bethel Colony were large communal enterprises outside of the area delineated for the town streets. There were a few specialists – the tailor and the school master, for example – but most of the men and boys of the Colony worked at agricultural tasks in this communal setting. Both the labor and the product of male work was communal.

The belief of the Colony leader, William Keil, that all should work for the common good did not, however, extend to communalization of traditional “woman’s work.” Housekeeping in the individual family homes remained the rule. Each household prepared its own meals, ate in its own home, and made clothes for its own children and female members. It also produced much of its own food: though red meat and staples were obtained from communal stores, individual kitchen gardens and orchards provided vegetables and fruits; and individual coops of chickens and geese provided the household’s eggs and featherbeds.

The community did provide some communal efficiencies that must have made it easier for Bethel’s women to do their work, but each household remained responsible for making use of them. A cow from the communal herd was brought to each household’s barn each evening, but it was members of the individual household who milked it and made any butter or cheese the family would have. There were several communal ovens, but women made their own bread and brought it to the ovens to be baked. A laundry shed next to the mill had hot water from the steam boiler piped in, but each family did its own laundry in the shed on an assigned day. Not having to fire your own oven or carry and heat your own wash water was no small improvement over the life of the typical farm household, but it did not relieve you of the basic task. The individual housewife, with whatever assistance she might receive from her children or other adult women living under her roof, remained individually responsible for house, garden, orchard, and henhouse.

Nothing in the scant written evidence left by the Bethel Colony suggests a reason for the difference in treatment of male and female labor or production. Dr. Keil did not leave documentation of his beliefs or reasons for them; he was opposed to such records, stating on one occasion that “under no condition would he be bound and fettered by any written agreement. If a man’s word was not as good as a written law, then he could and would have nothing to do with the project” (Bek 1909, 267). Whatever the reason, male labor and production were communal at Bethel and female labor and production were not – and the site planning of the Colony reflects this unique situation.

The 1785 Land Survey grid had created a norm for the physical environment of the American nuclear family. A traveler in the 1870’s described a scene like that which still greets the eye in many parts of the Midwest:

From the point where you leave the Alleghanies [sic] at Pittsburg [sic], until after crossing the Missouri . . . a railway run of some thousand miles, there is a uniformity of landscape greater than could be found along any one hundred miles of railway in Western Europe. Everywhere . . . one travels past farms of two or three hundred acres, in everyone of which there is a spacious farmhouse among orchards and meadows (Jackson 1972, 62-63).

Thanks to the grid pattern of landownership imposed by the Land Survey, these “spacious farmhouses” were both widely and evenly spaced. They sat not just among “orchards and meadows” but among vegetable gardens, wellhouses, chicken coops, woodsheds, and outhouses, which created what I will call a farmstead zone, a denser zone of both built form and activity between the house and the open fields. Activities conducted within this farmstead zone were traditionally the responsibility of the farmwife. It was she (with the aid of daughters and sons too young for the fields) who tended the gardens, harvested and preserved their production, fed and slaughtered the chickens and gathered their eggs, and carried in the wood for her stove. The larger barn and its yard, while situated near the farmstead for convenience, were nevertheless distinct from the farmstead zone and separated from it by roads or fences. Though the entire family might be needed in the fields at harvest time, the fields and barn around the farmstead were understood to be the domain of male responsibility.

The only piece of this traditional picture that was changed at Bethel was that the crop fields, pastures and large livestock facilities of the typical American family farm, the territory of male work, were physically separated from and located at considerable distance from the farmstead domain of female work. Farmsteads nearly a half an acre in size were then lined up next to each other on the streets of Bethel, with all their traditional functions complete. The significant physical change, in other words, was economic in origin: the collectivization of both the fields of the family farm and the male workforce.

That one change, however, collectivizing male labor and its setting, created something entirely new (Figure 6). The built environment of the town of Bethel consisted primarily of single family homes on nearly half-acre lots. The size of these lots and the consequent distance of one house from another meant that separating home from field did not simply recreate the form of the farm village in Europe or parts of early New England, in which houses placed close together for ease of protection housed farmers who went out to their fields by day. Nor did it produce the built environment typical of the American rural small town, in which the homes of those who serviced the surrounding farms (bankers, doctors, retailers, etc.) were typically placed in closer proximity to each other than were Bethel houses, and furthermore were often the site of male work, in offices or first-floor commercial space. Instead what it produced were streets of houses sitting right on the corners of large, open lots, which were the province of women and children during the day, while the men went off to work and came home to their dinners at night. To a late-20th century American this has a familiar ring; long before the 1950’s post-war sprawl, the Bethelites had created an American suburban environment.

Bethel’s was not the “borderland” version of a suburban environment that existed in the mid-19th-century near larger American cities, a zone Stilgoe defines as “between rural space and urban residential rings” (Stilgoe 1988, 9) in which well-to-do, commuting, city workers established ornamental country seats to which they could retreat from “the withering blasts of city living.” (Stilgoe 1988, 37). The town of Bethel sat squarely in rural space, 160 miles over mostly dirt roads from St. Louis, the nearest city, and not on a rail line. Instead, its nearly half-acre house lots on tree-lined streets created an early manifestation of what was a century later to become the aspiration of middle-class America: the low-density bedroom suburb.

There were, of course, certain obvious differences; if today’s upper-middle-class suburban housewife grows vegetables for the table on her half-acre it is by preference, not necessity. Change in both the specifics of and the physical difficulty of “women’s work” in the past century do not, however, alter the fundamental similarity; in Bethel, as in the “Stoneybrooks” and “Fox Hills” spread across American landscape in the latter part of the 20th century, men went elsewhere to work in company while women labored in relative isolation at home.

The low-density bedroom suburb has been called a creation of the capitalist system; it is therefore interesting to find that the same physical form serves both corporate capitalism and radical Christian Communism. The example of Bethel suggests very strongly that it is not capitalism per se that calls this particular suburban form into being, but the physical segregation of male labor from female domestic labor under either economic system.

The Bethel Colony was unlike other contemporary communal utopias, such as the Oneida Colony or the Bishop Hill Colony, in its economic structure. It allowed individual profit-making by members; a similar tolerance for individualism can be seen in its architecture. It did not communalize traditionally female work; this radically influenced its site planning, resulting in creation of an early manifestation of a low-density suburban plan. The particularities of its economic structure can thus been shown to be reflected in the built form it produced.

References

Bek, William G. “The Community at Bethel, Missouri, and Its Offspring at Aurora, Oregon.” German American Annals New Series 7.5 & 6 (1909): 257-76, 306-28.

Bower, Clarence. “Bethel.” History of Shelby County. Shelby Co. Historical Society, 1972. 68-75.

Jackson, John Brinckerhoff. American Space. The Centennial Years 1865-1876. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1972.

Stilgoe, John. Borderland: Origins of the American Suburb. 1820-1939. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 1988.

Author Biography

Janet R. White is an Assistant Professor at the UNLV School of Architecture. She earned her Master of Architecture degree from Columbia University and her doctorate in the History of Architecture and Urbanism from Cornell University. Her research interests include utopian and visionary architecture, particularly of the 19th century.