An Early Twentieth-Century Homestead in Northeastern Nevada

Marshall E. Bowen, University of Mary Washington

Introduction

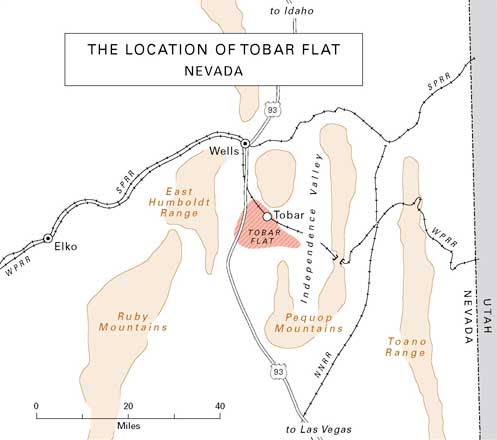

The dry valleys of the Intermountain West are dotted with abandoned homesteads that were occupied in the first years of the twentieth century. Those who come across vacant houses, caved-in wells, and remnants of cultivated fields rarely have much knowledge about the individuals who once lived on these sites, for the homesteaders and the people who associated with them have long since moved away, and in most cases are no longer alive. Questions about settlers’ origins, motives, and activities usually go unanswered, or generate only superficial answers, even from people in a position to know something about what took place in these out-of-the-way localities. Indeed, in describing the settlement of Tobar Flat, in northeastern Nevada, the former director of the local historical museum has written that about a mile south of the once-vibrant town of Tobar “are the concrete walls of one of the larger homesteads from the teens” (Hall 1998, 254), and leaves it at that. But through the use of published works, archival materials, and numerous other sources, it is possible to reconstruct the lives of the homesteaders, and to learn the details of how today’s relict landscapes evolved. This paper focuses on George E. Wickizer and his family, who lived on the homestead mentioned above from 1909 to 1913 (figure 1). It explains why Wickizer chose this site, describes his homestead and the activities that took place here, follows his footsteps after he left the area, and provides a glimpse of what the Wickizer place is like today, nearly a century after it was abandoned.

Figure 1. Location of Tobar Flat, Nevada. Maps by S.L. Dowdy.

George E. Wickizer was born in May, 1871, in Missouri, and grew up on farms in that state and in Iowa. He attended school on an irregular basis until he was fifteen years old, and often worked as a farm laborer for his father, other relatives, and neighbors. When George was in his early twenties he secured a position as a Western Union lineman, which took him to many parts of the West, including Colorado and Utah. He returned home in 1907 to marry Gertrude Wilkins, a native of Iowa, and shortly after their wedding the couple moved to Salt Lake City, where George resumed working for Western Union. It was here that Gertrude gave birth to their first child, a son named George Everett (called Everett to avoid confusion with his father), in September, 1908 (Burgess 1983, 7-11; Troxel 1985; U.S. Department of the Interior 1880a, 1880b; G.E. Wickizer 1931, 3-7, 114).

Site Selection

By this time the Western Pacific Railroad was under construction from Salt Lake City westward, and soon after his return to Utah, Wickizer joined a crew installing poles and telegraph lines along the new railroad’s right of way. The job was demanding, and many laborers, fed up with harsh conditions that included extremes of heat and cold as well as blowing alkali dust, and knowing that they would be laid off when trains began running, were on the lookout for better ways to make a living. Some men with farming experience thought that it might be possible to obtain homesteads near the railroad and settle down, but nothing that they had seen in the arid lands of western Utah and extreme eastern Nevada gave them any encouragement (Crump 1963, 22-26; Myrick 1962, 318-319; L.W. Wickizer 1985).

This began to change in the fall of 1908. As they pushed deeper into Nevada they could see the East Humboldt range, snow-clad in the winter and a sure source of water in the spring and summer, a few miles to the west. Soon, they spotted the channel of a stream called The Slough that delivered runoff from the mountains to land close to where the tracks would be laid. The Slough was dry right then, but the men agreed that with the return of warm weather it would probably carry enough water to moisten a considerable amount of farmland. Some individuals were skeptical about the quality of the area’s soil, but Wickizer, calling upon his experience on farms in the Midwest and believing that flat land was good land, declared that the country near The Slough looked more than adequate for crop production (L.W. Wickizer 1985).

A short time later, when crews of track layers and telegraph workers were gathered at a camp near the future site of Tobar, Wickizer and several other men took advantage of a brief respite from work to take a closer look at land between the camp and The Slough. The party covered several miles on foot, and during their expedition they visited a farm two miles to the west, where John C. Munson, a Utah-born freighter, had been producing satisfactory crops of grain, watered by natural overflow, since 1906. They also ventured to the south and southeast, and saw several sites where they thought it would be possible to match the success enjoyed by Munson (McDaniel 1979; Munson 1911; L.W. Wickizer 1985).

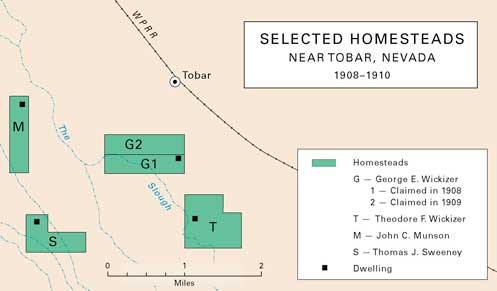

In November and December, 1908, Wickizer and five other individuals from the camp filed homestead claims on the land that they had examined earlier. Of these, Wickizer’s parcel lay closest to the Munson place, and consisted of a mile-long strip astride The Slough that he believed could be watered easily by overflow and seepage. Six months later, after passage of the Enlarged Homestead Act, he would claim another strip lying just north of his original entry (figure 2). Because of the geometry of the section in which these properties were located, Wickizer’s land covered only 316 acres instead of the maximum 320 acres allowed by the Enlarged Homestead Act (General Land Office n.d.; G.E. Wickizer 1912b; L.W. Wickizer 1985).

Figure 2. Selected Homesteads near Tobar, Nevada.

Getting Started

Wickizer spent the winter working along the line of the Western Pacific, but in April, 1909, in the company of three other men from the exploring party, he returned to Tobar Flat and put up a tent to protect him from the elements until he could build a more substantial structure. Just before this he had written to his younger brother, Theodore, who lived on a rented farm in Kansas, urging him to come to Nevada and informing him that land only a mile away, claimed by another member of the party, would become available because the man had changed his mind about living there. Theodore arrived about the first of May, and for more than a month the brothers stayed in George’s tent and began preparing his land for planting with the help of four horses that George had acquired and two that Theodore had brought from Kansas (Elko County 1909; General Land Office n.d.; Troxel 1985; G.E. Wickizer 1912b; T.F. Wickizer 1913; L.W. Wickizer 1985).

As summer approached, Wickizer started work on his house, assisted by his brother and Thomas J. Sweeney, a contractor from Salt Lake City who was building a similar structure on his own land two miles to the southwest. Wickizer mixed concrete in a trough, stirring it with a rake and carrying it in buckets to the house site, where he poured it by hand into wooden forms to create the lower story of what would become a six-room, two-storey structure. When this phase was completed, the men added a frame upper story, which they completed in November. Wickizer’s wife and son arrived from Utah during the summer, and after a short period of living in the tent, the family moved into its semi-finished house, which was located near the northeastern corner of the original entry (McDaniel 1979; Sweeney 1912; Teel 2005; G.E. Wickizer 1912b).

The Homestead

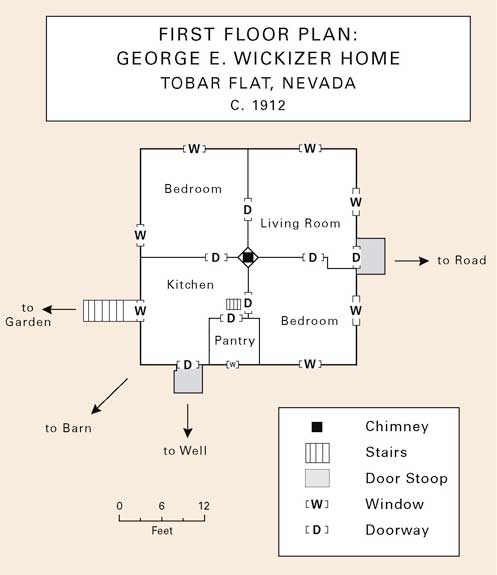

When completed, the Wickizer home measured 30 feet square, with exterior walls that were nine inches thick and interior walls of about half that thickness (figure 3). The front door, facing east, opened from a concrete stoop into a living room that was approximately 15 feet square, modified by a jog that served as an entryway and an indentation to accommodate the chimney. The parents’ bedroom, about the same size as the living room, occupied the northwest quarter of the house. A kitchen, pantry, and second bedroom completed the first floor arrangement. A door from the kitchen provided easy access to the family’s domestic well, just steps away, which according to a land office inspector reached water at a depth of about ten feet. A root cellar occupied space beneath the kitchen, and was accessible from the garden via six concrete steps, and from the kitchen itself by a set of steep wooden stairs. The layout of the second story is less certain, but if the entire house resembled the Sweeney residence, as the present owner of the latter property maintains, it probably consisted of little more than an attic that was used for storage (Kingsbury 1913; Teel 2005; G.E. Wickizer 1912b).

Figure 3. First Floor Plan: George E. Wickizer Home.

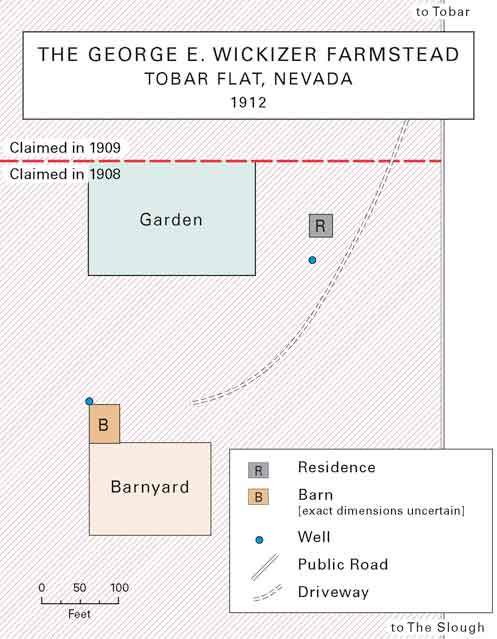

The farmstead was simple and utilitarian (figure 4). A garden covering almost an acre was laid out behind the house, and could be watered from the family’s domestic well. South of the garden and southwest of the house stood a lumber barn with a dirt floor. The barn may have been about 40 feet by 50 feet in size, but since the structure never accommodated more than four horses and three milk cows, and stored only a limited amount of hay, it is possible that it was not this large. It was certainly smaller and less elaborate than Theodore’s barn, which had a solid wooden floor and was the scene of numerous dances and other social events in the fledgling homesteader community. Behind the barn was a fenced enclosure that resembled a Midwestern barnyard. The family’s livestock were watered from a trough, filled from a well at the northwestern corner of the barn, that ran the length of the barn and extended a short distance into the barnyard (Elko County 1910-1912; Troxel 1985; G.E. Wickizer 1912b).

Figure 4. The George E. Wickizer Farmstead

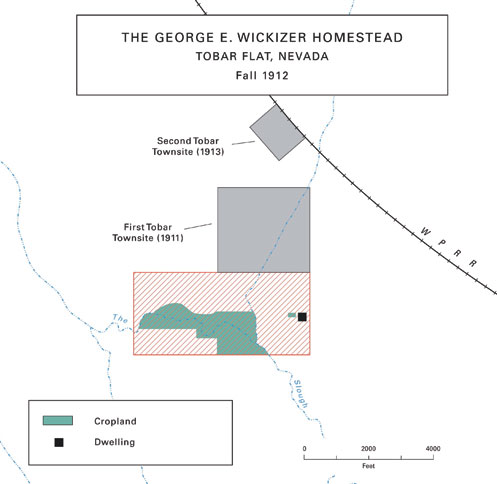

Figure 5. The George E. Wickizer Homestead, Fall 1912

With the exception of the garden, all cropland was situated at some distance from the family’s dwelling, and was positioned to take advantage of natural overflow and seepage from The Slough (figure 5). Wickizer planted more than 20 acres of grain and alfalfa in 1909, and in the following years he expanded the amount of cropland so that when he proved up in October, 1912, he had 65 acres under cultivation, although not all of this was in crops that year. His largest and most frequently-used field began a few hundred yards southwest of the house, and was laid out in a way that would enable it to receive water from The Slough and, whenever possible, from a small runoff channel originating northeast of Tobar (G.E. Wickizer 1912b).

Agricultural Failure

Despite considerable effort, Wickizer’s crops did not do well. The first disaster occurred early in the summer of 1909, when cattle belonging to John C. Munson got into his freshly planted fields, which had not yet been fenced, and destroyed the crops. Determined that his first year of farming would not be a total loss, Wickizer acted quickly to get something from the land that he and his brother had prepared. As he put it, “then I done my fenceing [sic] & disked my grain up & sowed 13 acres of Turkey red Wheat & 13 acres of Winter Rye in september, 1909” (G.E. Wickizer 1912a). But these winter crops fared little better than those planted in the spring. When he harvested them in the late summer of 1910, he obtained only 67.5 bushels of grain, a disappointing average of barely more than 2.5 bushels per acre. Part of the problem was insufficient rainfall, but another reason was that by now Munson had built an earthen dam across The Slough, holding back some of the water that Wickizer had expected to receive (Munson 1908; Munson 1911; G.E. Wickizer 1912b).

Wickizer’s fortunes did not improve in the following years. He anticipated good crops in 1911, but a long dry spell in late summer doomed his grain, and he harvested only 155 bushels from more than 50 acres. The next year his winter wheat was almost completely destroyed by cold weather. He replaced the winter-killed wheat with oats and barley, but these did not do well, either, and had to be pastured. The closest approximation of success, and it was a small one, occurred in 1911 when he dug up 25 sacks of potatoes from a two acre-field (Nevada State Herald 1911a, 1911b; G.E. Wickizer 1912b).

Without good yields, Wickizer had no grain to sell, and was hard put to provide feed for his livestock. The family was able to survive only because its garden and potato patch were fairly productive and because Thomas J. Sweeney gave George occasional work on construction projects at the first Tobar townsite, located just to the north. He was a personable man, well-liked and respected by most of his neighbors, who elected him to a four-year term on the Tobar school board, but neither his popularity nor his position on the school board generated any income. His financial difficulties were compounded because he was obliged to send money to his elderly father, who was no longer able to work. It was clear that the Wickizers’ resources were being stretched to the limit, particularly after their second child, a daughter whom they named Eulah, was born in the spring of 1911. The combination of poor crops, too little money, and having four mouths to feed became an insurmountable obstacle, and in early 1913 Wickizer gave up. He disposed of his livestock and farming equipment, and once this was completed, he went to California to resume working for Western Union, leaving his wife and children behind in the care of his brother. Theodore Wickizer may have cultivated some of George’s land in 1913, but this did not last for more than one season, and by 1914 the house and fields stood completely abandoned (Elko County 1913-1914; Nevada State Herald 1911a, 1912; Olmsted 1911; Sweeney 1912; Troxel 1985; G.E. Wickizer 1931, 150).

Afterwards

Wickizer stayed in California for about a year, and was then transferred to Denver, where Gertrude and the children joined him. In 1916 George was promoted to the position of inspector, and by 1918 he was able to purchase a modest house in one of the city’s working-class neighborhoods. Unfortunately, marital harmony did not accompany economic progress, in part because George had to be away from home for weeks at a time and partly because Gertrude had become deeply involved with the Seventh-day Adventist Church, which George detested. The couple separated in 1921, and after a bitter and sometimes violent battle over custody of the children and division of their property, they divorced. George rented a furnished room in downtown Denver, but he was often away from the city for extended periods of time, working in Utah, Wyoming, and Montana. By 1930, at the age of fifty-nine, he was back in Denver on a more or less permanent basis, living with his daughter, Eulah, and her husband (Elko County 1915-1930; Roberts, 1915-1930; Troxel 1985; U.S. Department of the Interior 1920, 1930; G.E. Wickizer 1931, 89-208; L.W. Wickizer 1985).

During these troubled times Wickizer wrote a book, published in 1931, that was essentially a religious tract but also included bits of information about his early life and devoted a great deal of attention to the circumstances of his divorce. The book said nothing about the family’s period of residence in Nevada. Gertrude Wickizer remained in Denver for the rest of her life, first operating a sewing machine at a dress factory and later working as a seamstress at home. Everett also stayed in the Denver area, usually living with his mother, until he was killed in a motorcycle accident in 1938. George retired from Western Union in the mid-1930s, and moved to Massachusetts to live with Eulah and her family, who had relocated to the Boston area, and it is here that he died in 1940 (Burgess 1983, 7-8; Manning 1940, 138 and 562; Roberts 1931-1935; Troxel 1985; G.E. Wickizer 1931; L.W. Wickizer 1985).

Wickizer retained ownership of his property on Tobar Flat until 1935, but in the depths of the Great Depression, at about the time he retired from Western Union and left Colorado, he defaulted on his real estate taxes and the land was taken over by Elko County. The county held it until 1947, when it was sold to a local rancher who was acquiring numerous abandoned homesteads in the area. The rancher leased the land to an oil company for exploration purposes in the mid-1950s, but nothing came of this venture, and since that time it has remained firmly in the hands of this man and his family. Cattle occasionally graze here, but for the most part the property lies untouched, the silence broken only by the wind (Elko County 1915-1935; Elko County 1955-2007; McElrath 1961; Pengelly 1982; Title Abstracts 1913-1955).

The Homestead Today

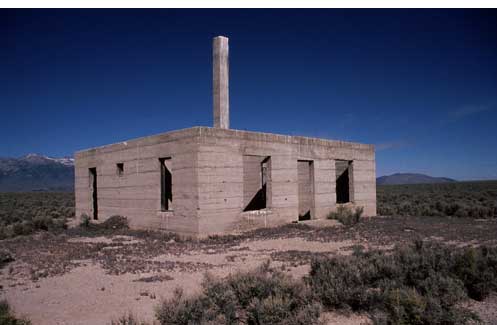

Figure 6. The George E. Wickizer Home. All photos by Marshall E. Bowen, 2006.

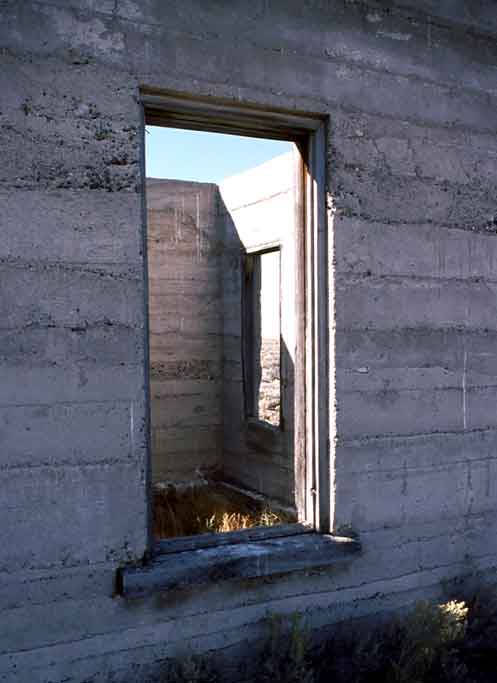

Figure 7. Window on north side of house.

Figure 8. Boot scraper on front stoop.

Figure 9. Entrance to root cellar.

Although it has been unoccupied for almost a hundred years, this homestead site still yields valuable clues about a way of life that has disappeared from northeastern Nevada. The first story of the house looks very much as it did when the Wickizers lived here, with openings for the front door, kitchen door, several large windows, and a small pantry window clearly visible (figure 6). At some windows, the ledge and frame remain more or less intact (figure 7). A rusted boot scraper is embedded in the front stoop, conveniently placed where Wickizer would have approached the door when coming from his fields or the barn (figure 8). The entrance to the root cellar is well preserved, while the cellar itself contains both concrete walls and a wall of native rock (figures 9 and 10). Just beyond the kitchen door is the family’s domestic well, with a twisted old pipe emerging from the caved-in depression (figure 11). To the southwest lie the remains of the second well (figure 12), boards scattered about where the barn once stood, and fence posts that outline the size and shape of the barnyard. Disturbed land behind the house shows where the garden was once located and, farther away, similar scars support Wickizer’s statements about the location and size of his hay and grain fields (figure 13).

Figure 10. Interior of root cellar.

Figure 11. Remains of domestic well.

Figure 12. Remains of stock well.

Figure 13. Part of Wickizer garden.

Conclusions

Three principal conclusions can be drawn from this study. First, by piecing together the life histories of ordinary people like the Wickizers, we can come closer to understanding what northeastern Nevada’s early twentieth-century homesteaders were like, why they chose to live in places like Tobar Flat, what the homesteading experience entailed, why they left, and what these people did with their lives after they gave up trying to wrest a living from such unforgiving land. Second, it becomes clear that while some homesteaders may have been fiercely independent and completely isolated from those around them, it is safe to say that most settlers, including the Wickizers, experienced close interactions with their neighbors, some of a positive nature and others less so. It is unlikely that the family could have settled in so readily, or remained on the land as long as it did, without the assistance that George received from his brother and from Thomas J. Sweeney, and the friendships that connected him with these and other neighbors. But it is equally correct to say that the Wickizers might have remained longer if their crops had done better, and that John C. Munson’s marauding cattle and his dam on The Slough were just as responsible for their failure as were drought and cold weather. Finally, the Wickizers’ house and other remnants of the homestead’s built landscape enable us to appreciate the efforts of the men who produced them, and to imagine the day-to-day lives of the people who lived there. The George E. Wickizer homestead provides a window into a nearly-forgotten dimension of western America’s past, and should be recognized as a valuable element of the region’s heritage.

References Cited

Burgess, M.W. 1983. The Wickizer Annals. San Bernardino, CA: The Borgo Press.

Crump, S. 1963. Western Pacific: The Railroad that was Built Too Late. Los Angeles: Trans-Anglo Books.

Elko County. 1909-1935. Tax Assessments. Elko County Court House, Elko, NV.

_____. 1955-2007. Land Ownership Records. Elko County Court House, Elko, NV.

General Land Office. n.d. Nevada Tract Books, Record Group 49, National Archives, Washington, DC.

Hall, S. 1998. Old Heart of Nevada: Ghost Towns and Mining Camps of Elko County. Reno: University of Nevada Press.

Kingsbury, J.W. 1913. Letter to the Commissioner, General Land Office, 14 May. Attached to Homestead Serial Patent Application 401131, Record Group 49, National Archives, Washington, DC.

Manning, H.A. 1940. Somerville (Massachusetts) Directory. Boston: H.A. Manning Co.

McDaniel, W.B. 1979. Interview by author, McGill, Nevada, 4 July.

McElrath, J.. 1961. “The Sign Pointed Thirsty ‘To Bar.’” Nevada State Journal, 21 May.

Munson, J.C. 1908. Application for Permit to Appropriate the Public Waters of the State of Nevada, 2 December. File 1201-1202, Nevada Division of Water Resources, Carson City, NV.

_____. 1911. Statement of 8 March. Homestead Serial Patent Application 208931, Record Group 49, National Archives, Washington, DC.

Myrick, D.F. 1962. Railroads of Nevada and Eastern California, vol. 1, The Northern Roads. Berkeley, CA: Howell-North Books.

Nevada State Herald. 1911a. Wells local news. Nevada State Herald, 17 March.

_____ 1911b. Wells local news. Nevada State Herald, 25 August.

_____ 1912. Wells local news. Nevada State Herald, 3 August.

Olmsted, A.C. 1911. Record of Births kept by A.C. Olmsted, M.D., Wells, Nevada, 1897-1914. Nevada Historical Society, Reno, NV.

Pengelly, E. 1982. Interview by author, Wells, NV, 22 June.

Roberts, W.H. 1915-1935. Denver Directory. Denver: Will H. Roberts and the Denver Gazetteer.

Sweeney, T.J. 1912. Statement of 2 October. Homestead Serial Patent Application 321928, Record Group 49, National Archives, Washington, DC.

Teel, C. 2005. Interview by author, Tobar Flat, NV, 23 September.

Title Abstracts. 1913-1955. First American Title Company, Elko, NV.

Troxel, O.W. 1985. Interview by author, Wauneta, Nebraska, 20 July.

U. S. Department of the Interior, Census Bureau. 1880a. Manuscript Schedules for Fremont County, Iowa. National Archives, Washington, DC.

_____. 1880b. Manuscript Schedules for Woodbury County, Iowa. National Archives, Washington, DC.

_____. 1920. Manuscript Schedules for Denver County, Colorado. National Archives, Washington, DC.

_____. 1930. Manuscript Schedules for Denver County, Colorado. National Archives, Washington, DC.

Wickizer, G.E. 1912a. Letter to Louis J. Cohn, Register, U.S. Land Office, Carson City, Nevada, 10 October. Attached to Homestead Serial Patent Application 321923, Record Group 49, National Archives, Washington, DC.

_____. 1912b. Statement of 17 October. Homestead Serial Patent Application 321923, Record Group 49, National Archives, Washington, DC.

_____. 1931. The Aquarian Age of Man. Denver: Privately Published.

Wickizer, L.W. 1985. Telephone interview by author, Stratton, Nebraska, 22 August.

Wickizer, T.F. 1913. Statement of 18 November. Homestead Serial Patent Application 402570, Record Group 49, National Archives, Washington, DC.