Whistle at Your Own Risk: The Changing Landscape of Music in New Orleans During the Civil War

Ralph Hartsock, University of North Texas

Since its founding in 1718, New Orleans has become a booming metropolis, with several cultural activities. During the nineteenth century, opera, symphony, and folk music flourished. Classical performers came from afar to perform here, including Belgian virtuoso violinist and composer Henri Vieuxtemps and Norwegian violinist Ole Bull, and singers Julie Calve and Adelina Patti. Theatre d’ Orleans, founded in 1819 by John Davis (1773-1839), performed 52 American premieres in its first five years. (Joyce n.d.) The troupe toured the northeastern United States from 1827 to 1833, giving residents of New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore their first hearing of operas by Daniel François Esprit Auber, François Adrien Boieldieu, Gaspare Spontini, Ferdinand Hérold, Nicolo Isouard and Gaetano Donizetti. James Caldwell, a rival, had opened the Camp Street Theatre in 1824, where he produced musicals and plays in English, and Italian operas in English translation. According to Susan Thiemann Sommer, author of the article on “New York,” in the New Grove Dictionary of Music, New York’s first opera house, the Italian Opera House at Church and Leonard Streets, opened on November 18, 1833 with Rossini’s La Gazza Ladra (Sommer n.d. 2008). The Metropolitan Opera was not founded until 1883. Thus, during the antebellum era, one was more likely to hear the American premiere of a European opera in New Orleans than in New York.

The Classical Musical Society was founded in 1855. In 1859, the French Opera House was built, and became the site of 17 American premieres of European operas. New Orleans also had its own musicians who gained international stature, among them Louis Moreau Gottschalk. At the beginning of the Civil War, brass bands and military music also flourished in the city.

Music publishers in pre-Civil war New Orleans included Paul Emile Johns, William T. Mayo, Philip P. Werlein, and Louis Grunewald. Paul Emile Johns (1798-1860), born in Krakow, Poland, had immigrated to New Orleans by 1820. By 1822 he had a listing as a piano teacher, and in 1823 the Paxton’s New Orleans directory listed him as a “pianiste” (Baron 1972, 246). Johns accompanied traveling virtuosi of the voice or instruments at concerts in New Orleans, performing at the Theatre d’ Orleans. Known as Emile Johns in New Orleans, this Polish-born immigrant opened a retail shop in 1830 (Joyce), and began to sell music in New Orleans; he flourished as the chief representative in that city for the French firm, Pleyel and Sons (Ignaz Pleyel and his son, Camille Pleyel). In addition to publishing music, he sold and distributed music of other publishers, such as John Blockley’s List to the Convent Bells: it had the stamp or printing on the music “For sale by E. Johns & Co., New Orleans” (Blockley n.d.; Knight n.d.). Johns composed and distributed Album Louisianais, a publication of the Pleyel firm in Paris (Johns 1837).

Johns sold his firm to William T. Mayo (1807-1892) in 1846. Prior to this purchase, Mayo had forged connections with publishers in other cities, Frederick D. Benteen and George Willig in Baltimore, Lee & Walker in Philadelphia, and Firth, Pond, & Co. in New York. He was listed as a secondary publisher in several editions of sheet music. One of his earliest independent publications was the Genevieve Waltz, by a Lady of New Orleans, a pseudonym of Marion Southwood (Southwood n.d.). Another early publication was a song about the War with Mexico, The Victory of Monterey, by John Thuer (Thuer 1845). From his office at 5 Camp Street in New Orleans, Mayo issued hundreds of other pieces of music over the next decade. (Strakosch n.d.)

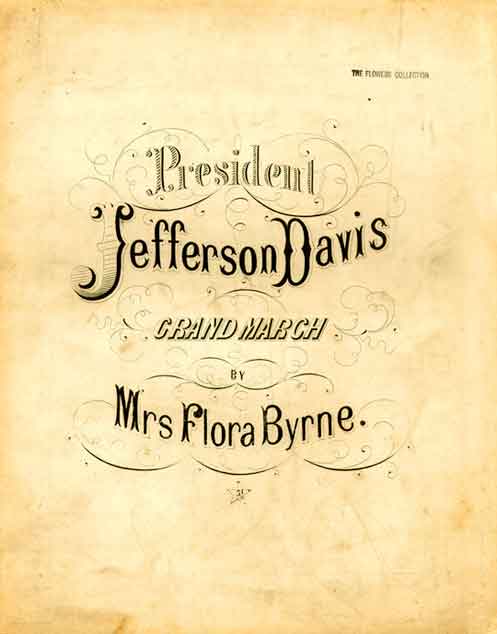

Mayo sold his publishing venture in 1854 to Philip P. Werlein (1812-1885), a Bavarian immigrant known as the first Southern publisher of Dan Emmett’s Dixie in 1860 (Emmett 1860). Werlein continued to publish several songs that spoke to the South during the Civil War, such as Flora Byrne’s President Jefferson Davis Grand March (Byrne 1861; see figure 1).

Louis Grunewald (1827-1915), of German birth, immigrated to New Orleans in 1852, performing as an organist in several Catholic churches in that city (Abel 2000, 268; derived from Boudreaux 1977, 72). In 1856 he opened his New Orleans music publishing business on Magazine Street; his imprint was first used in 1858, and he became the most prolific of all publishers in the city (Baron 1980; Abel, 291). He also sold musical instruments, such as pianos, drums, and fifes, as exhibited by his advertising in the Times Picayune of January 26, 1861, February 6, 1861 (figure 2), March 6, 1862, and even April 23, 1862, after the Union’s occupation (see also Abel, 152). The store continued to operate into the 1970s. The publishing firm moved to 214 Constance Street (1859), 26 Chartres Street (1861), and 129 Canal Street (1863). Grunewald was not openly Confederate, as were Armand Blackmar and Philip Werlein, and his music was not overtly patriotic (Abel, 268; Schrenk 1861). Thus he remained open during the Civil War. Grunewald was a very successful businessman, who by the century’s conclusion, owned an opera house and a hotel, “The Grunewald” (figure 3). This hotel eventually became the Fairmont Hotel, but closed due to damage by Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

Figure 1. “President Jefferson Davis Grand March,” (Byrne 1861). Courtesy Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library.

Figure 2. Grunwald ad from the Times Picayune, February 6, 1861.

Figure 3. Post-card depiction of the Grunwald Hotel.

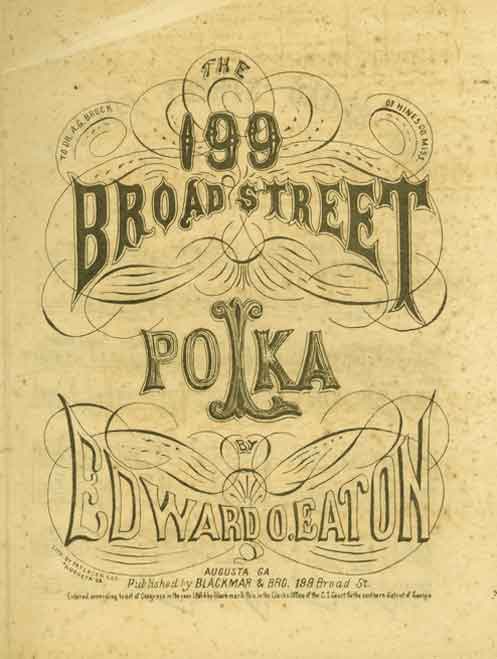

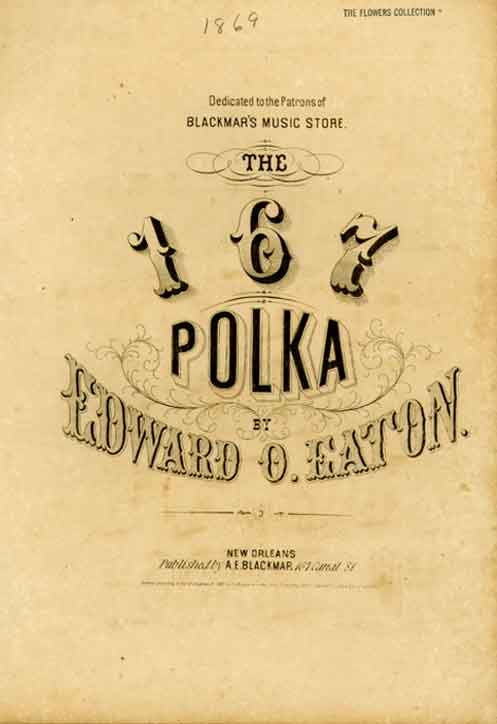

One advertising tactic used by these publishers was to publish music that depicted their address. Louis Grunewald commissioned Charles Mayer (1799-1862) to compose the 129 Canal Street Quick March, also called the 129 Canal Street Polka (Mayer 1864). Edward O. Eaton composed the 199 Broad Street Polka (Eaton 1864; see figure 4) for Blackmar and Bro. while they were in Augusta, Georgia. He later composed the 167 Polka for A.E. Blackmar, whose publishing house was at 167 Canal Street in New Orleans (Eaton 1865; see figure 5).

Figure 4. “The 199 Broad Street Polka” (Eaton 1864). Courtesy Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library.

Figure 5. “The 167 Polka” (Eaton 1869). Courtesy Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library.

The Blackmars in New Orleans

One publisher who took risks more than others was A.E. (Armand Edward) Blackmar. Harmon Edward Blackmar was born in Bennington, Vermont, on May 30, 1826, the son of Reuben Harmon Blackmar and Amana Cushman Blackmar; both claimed to be descended from Pilgrims. A younger brother, Henry Clay Blackmar, was born in 1831(Mount 1896, 121). In 1836, the family moved to Cleveland, Ohio. Henry attended the old-time singing school, and later studied flute and violin. Paul Powell and other scholars have assumed that Harmon had received similar music education (Powell 1978, 5). Harmon then attended Western Reserve College in Cleveland (known today as Case Western Reserve University), graduating in 1845.

In 1852, Harmon moved to Jackson, Louisiana, serving as a music professor at Centenary College, remaining in the position until 1855. Powell speculates that it was during this period of teaching that Blackmar changed his name to Armand (Powell, 7). By 1856, he returned to Jackson, Mississippi, and opened his first piano and music store. He published no music, but he was listed as a subsidiary publisher to P.P. Werlein. In 1858, Blackmar established a second store in Vicksburg, and partnered with E.D. Patten, known variously in WorldCat (OCLC 1971; Waldauer 1858) as “Blackmar & Patten” or “Patten & Blackmar.” Powell spelled this as Patton. Here he sold musical instruments and sheet music of other publishers.

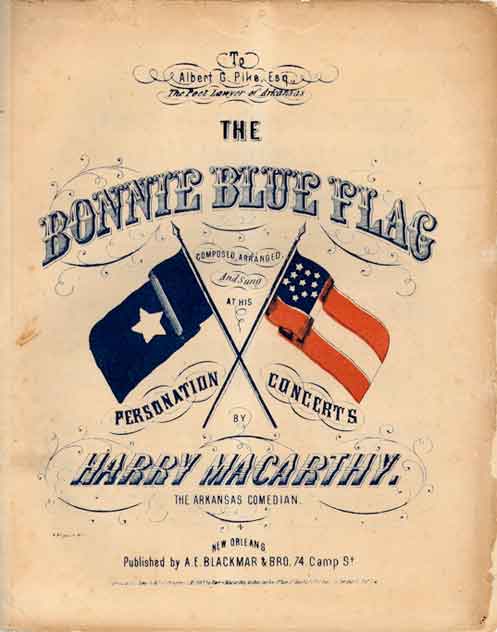

Beginning in 1860, Blackmar issued more Confederate music than any other publisher in New Orleans, including early editions of Dixie, The Bonnie Blue Flag (figure 6), and Maryland! My Maryland! Like Emile Johns and Louis Grunewald, a substantial portion of Blackmar’s business was publishing, but he also sold music from other publishers, and instruments. Back covers include advertisements for pianos, melodeons, organs, guitars, violins, flutes, and brass instruments (Powell, 17). In 1861, he married Margaret Meara, who had been born in Ireland. Their first child of four, a daughter, was named Louisiana Rebel, called “Lulu” by the family. This southern will had extended far beyond Blackmar, though. Early in 1862, as Farragut’s soldiers lowered the Confederate flag in New Orleans, a crowd marched to the river, led by a woman with a Confederate banner, and a fifer, playing the Bonnie Blue Flag and Dixie. (Hearn 1997, 69)

Figure 6. “Bonnie Blue Flag” (Macarthy 1861). Courtesy Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library.

On numerous occasions, Harry Macarthy (1834-1888), the poetic creator of The Bonnie Blue Flag, performed at the Academy of Music in New Orleans (Times Picayune April 21, 1862). The Irishman had dubbed himself “The Arkansas Comedian.” (Macarthy 1861) In September of 1861, Macarthy sang The Bonnie Blue Flag at the Academy, to a house filled with Confederate soldiers. Accompanied by his sister, Marion, this song caused great excitement among the soldiers (Rutherford 1907).

On May 1, 1862, Admiral David G. Farragut turned control of New Orleans over to General Benjamin Butler, who considered The Bonnie Blue Flag to be “seditious” (Abel). Butler fined Blackmar five hundred dollars, and sent him to a jail on Ship Island for a brief period; as he was escorted to jail, the publisher defiantly whistled The Bonnie Blue Flag. While Armand was in prison, Henry smuggled several music plates and other supplies out of New Orleans and took them to Augusta, Georgia. Butler later confiscated all remaining music at Blackmar’s New Orleans publishing venture.

So enraged by the hearing of The Bonnie Blue Flag was General Butler that he “issued an order that any man, woman or child that sang that song, whistled or played it, should be fined twenty-five dollars” (Rutherford, 254). But even these measures could not quell the hearts of those who sang what became the “Marseillaise of the South” (254).

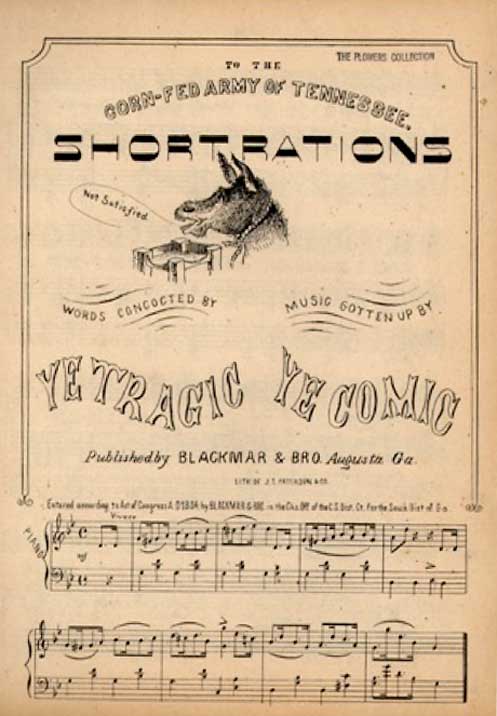

Undaunted, in spite of his imprisonment, A.E. Blackmar remained in New Orleans, even after his release. He used various pseudonyms, including S. Low Coach, Ducie Diamonds, A. E. A. Muse, A. Noir, A. Pindar, Schwartz, The Voice of the South, and Ye Comic (Drone 2007). Blackmar had quite a sense of humor, that he transferred to his publishing business. Short Rations (figure 7), a song dedicated to the “Corn-Fed army of Tennessee,” had words concocted by “Ye Tragic” (John Alcée Augustin, 1838-1888), and music gotten up by “Ye Comic” (A.E. Blackmar) (Ye Comic 1864). He published Goober Peas under two pseudonyms: the words of A. Pindar, Esq., and music by P. Nutt, Esq. (Harwell 1951, 100-101; Nutt 1866; Powell, 36). For the 1868 presidential election, Théodor von La Hache (1823-1867) had composed a humorous song, Let Us Have Pease, Ha, Ha. In the background, a clerk is transcribing “Let us have peace,” a line from Ulysses S. Grant’s acceptance speech on May 29, 1868, at the Republican Convention. In the foreground, the line is “Let Us Have Pease,” as the general and others eat (La Hache 1868).

Figure 7. “Short Rations” (Ye Comic 1864). Courtesy Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library.

In the 19th century American musical landscape the piano became more common in parlors as families and friends gathered for the evening’s entertainment. Annual sheet music production increased from 600 titles in the 1820s to 5,000 in the early 1850s (Cornelius 2004, 18-20). Even during the changing landscape of music and musical purchasing in the Civil War, people still bought music and instruments, especially pianos. In 1866, Americans purchased 25,000 new pianos at $15 million. Boston publisher Oliver Ditson had an inventory of 33,000 piano pieces; by the 1870s this had increased to 200,000 (Blumhofer 2005, 151). Our publisher went on to San Francisco from 1877 to 1880, but returned to New Orleans in 1881. Publishing well into the 1880s, he died October 28, 1888, in New Orleans. During his lifetime, A.E. Blackmar exerted a large influence on music publishing in the South, producing almost one third of all sheet music published in the region. I conclude with this: in the 20th century, the musical The King and I featured the song, “I’ll Whistle a Happy Tune.” But in Civil War New Orleans, those who tested the limits in their society, particularly in music publishing, whistled at their own risk.

References Cited

Abel, E. L. 2000. Singing the New Nation: How Music Shaped the Confederacy, 1861-1865. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books.

Baron, J. 1972. “Paul Emile Johns of New Orleans: Tycoon, Musician, and Friend of Chopin.” International Musicological Society Congress Report 11, 246-250.

_______. 1980. Piano Music from New Orleans, 1851-1898. New York: Da Capo Press.

Blockley, J. n.d. List to the Convent Bells: Notturno for One or Two Voices. Philadelphia: George Willig.

Blumhofer, E. L. 2005. Her Heart Can See: The Life and Hymns of Fanny J. Crosby. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans.

Boudreaux, P. 1977. “Music Publishing in New Orleans in the Nineteenth Century.” MA thesis, Louisiana State University.

Byrne, F. 1861. President Jefferson Davis Grand March. New Orleans: P.P. Werlein & Halsey. Citation on figure as Historic American Sheet Music, “President Jefferson Davis Grand March,” Conf. Music #332, Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library, http://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/hasm.conf0332/pg.1/, last accessed Sept. 10, 2008.

Cornelius, S. H. 2004. Music of the Civil War Era. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Drone, J. M. 2007. Musical AKAs: Assumed Names and Sobriquets of Composers, Songwriters, Librettists, Lyricists, Hymnists, and Writers on Music. Lanham, MD : Scarecrow Press.

Eaton, E. O. 1864. The 199 Broad Street Polka. Augusta, GA: Blackmar & Bro. Citation on figure as Historic American Sheet Music, “The 199 Broad Street Polka,” Conf. Music 86, Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library, http://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/hasm.conf0086/pg.1/, last accessed July 16, 2008.

_______. 1869. The 167 Polka. New Orleans: A.E. Blackmar. Citation on figure as Historic American Sheet Music, “The 167 Polka,” Music B-943, Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library, http://scriptorium.lib.duke.edu/sheetmusic/b/b09/b0943/, last accessed July 2, 2008.

Emmett, D. D. 1860. I wish I was in Dixie’s Land. New Orleans: P. P. Werlein.

La Hache, T. von. 1868. Let Us Have Pease, Ha, Ha. New Orleans: A.E. Blackmar. Citation on figure as Library of Congress Music Division Washington, D.C., M1642.L Case c-MUSIC, http://lcweb2.loc.gov/pp/pphome.html, last accessed July 2, 2008.

Harwell, R. B. 1951. Songs of the Confederacy. New York: Broadcast Music, Inc.

Hearn, C. G. 1997. When the Devil Came Down to Dixie: Ben Butler in New Orleans. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Johns, E. 1837. Album Louisianais: hommage aux dames de la Nouvelle Orléans, contenant six romances, une walse & une polonaise. Paris: I. Pleyel & Co.; Nelle Orleans: E. Johns & Co.

Joyce, J. n.d. “New Orleans.” In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/42080, last accessed July 9, 2008.

Knight, J. P. n.d. She Wore a Wreath of Roses. Philadelphia: George Willig; New Orleans: Emile Johns.

Macarthy, H. 1861. Bonnie Blue Flag. New Orleans: A. E. Blackmar & Bro. Citation on figure as Historic American Sheet Music, “Bonnie Blue Flag,” Conf. Music #7, Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library. http://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/hasm.conf0007/pg.1/, last accessed Sept. 10, 2008.

Mayer, C. 1864. 129 Canal Street Quick March. N.P.: Louis Grunewald.

Mount, M. W. 1896. Some Notables of New Orleans. New Orleans, LA: M.W. Mount.

Nutt, P. 1866. Goober Peas. New Orleans: A.E. Blackmar.

OCLC. 1971. WorldCat. Dublin, OH: OCLC, http://newfirstsearch.oclc.org/dbname=WorldCat;done=http://REFERER/dbs.cfm;FSIP, last accessed September 10, 2008.

Powell, R. P. 1978. “A Study of A.E. Blackmar and Brother, Music Publishers of New Orleans, Louisiana, and Augusta, Georgia.” MLS thesis, Louisiana State University.

Rutherford, M. L. 1907. The South in History and Literature. Atlanta, GA: The Franklin-Turner Company.

Schrenk, J. 1861. Tiger Rifles Schottisch. New Orleans: Louis Grunewald. Citation on figure as Historic American Sheet Music, “Tiger Rifles Schottisch,” Conf. Music #411, Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library, http://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/hasm.conf0411/pg.1/ , last accessed Sept. 10, 2008.

n.d. “New York.” In S. Sadie, ed., The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. Oxford Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/O005554, last accessed July 9, 2008.

Southwood, M. n.d. Genevieve Waltz. New Orleans: Wm. T. Mayo.

Strakosch, M. n.d. Sea Serpent Polka. Boston: G.P. Reed; New Orleans: William T. Mayo. Citation on figure as Historic American Sheet Music, “Sea Serpent Polka,” Music A-8610, Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library, http://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/hasm.a8610/pg.1/, last accessed Sept. 10, 2008.

Thuer, J. 1845. The Victory of Monterey: A Brilliant Quickstep. New Orleans: Wm. T. Mayo.

Times Picayune (New Orleans, LA) 1861-1862.

Waldauer, J. 1858. The Bouquet Schottische. New Orleans (5 Camp St., New Orleans): P.P. Werlein; Mobile: Joseph Bloch; Vicksburg: Blackmar & Patten.

Ye Comic. 1864. Short Rations. Augusta, GA: Blackmar & Bro. Citation on figure as Historic American Sheet Music, “Short Rations,” Conf. Music 361, Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library, http://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/hasm.conf0361/pg.1/, last accessed Aug. 6, 2008.