Book Review

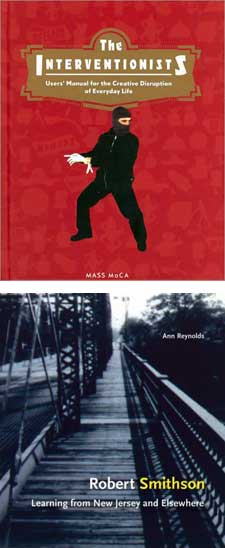

The Interventionists: Users’ Manual for the Creative Disruption of Everyday Life, second edition

Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2005

154 pages. Illustrations

$30 (cloth), ISBN 0-262-20150-X

Robert Smithson: Learning from New Jersey and Elsewhere

Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003

364 pages. Illustrations

$43.95 (cloth), ISBN 0-262-64155-2; $26.95 (paper), ISBN 0262681552

The “stuff of everyday life” and “material culture” are hot phrases once again in the art world, even if they are pinned to such extremely rarified objects as nickel surfboards and a marble chaise longue, bizarre artifacts featured in the designer Marc Newson’s exhibition in the Gagosian Gallery in New York City (February 2007). The transposition of this vocabulary from the world of dissertations into gallery releases and advertisements deserves consideration. The movement indicates increased porosity in the categorization of art and design in multiple levels of mass consumption. However, while the conceptual frameworks of material culture studies (or at least a superficial mention of the phrase) are in vogue in contemporary art practice, they are only beginning to be integrated into the curriculum of academic art schools. As an historian of decorative arts and design who teaches in a school of art and design, deciding how and when to teach material culture as a subject and/or a theoretical perspective are questions that prompt much text-searching in addition to soul-searching. Two recent publications, The Interventionists: Users’ Manual for the Creative Disruption of Everyday Life and Robert Smithson: Learning from New Jersey and Elsewhere, are worth noting and comparing especially because of their relevance to contemporary interpretations of “everyday life” and material culture in studio art practice. They were intended for different audiences and juxtaposed they document the enigmas in defining “everyday life” in relation to fine art. In our era of globalization, and increasingly ubiquitous commodity culture, it is especially unclear what constitutes the “everyday.” The terminology has a long provenance in Marxian history and criticism (most notably Henri Lefebvre, Fernand Braudel, Michel De Certeau, and Raymond Williams) as an alternative space to the canons of Western culture but remains enigmatic. Is it a classification of space outside of cultural labor or in antithesis to it? Can the “everyday” be invoked with consensus or does it fragment along issues of race, class, and gender?

The Interventionists is a manifesto for the rights of diverse expressions of political art. Its editors, Nato Thompson and Gregory Sholette, are two artist-provocateurs with distinguished careers as educators in a variety of institutional settings. The text served as a catalogue to accompany their exhibition, The Interventionists: Art in the Social Sphere at MassMoCA (May 2004–March 2005), where Thompson is an Assistant Curator. Masquerading tongue-in-cheek as an instructional booklet, the artful design is a humorous conceit. The didactic tone of the catalogue intentionally alludes to radical utopian Modernism and other periodic flowerings of politicized art movements, but is also ironic and self-deprecating. The layout of colorful banners and multiple fonts emulate the lurid hucksterism of commercial mass-mailings as well as intentionally alluding to bold revolutionary designs. Die-cut thumb tabs for each of the four thematic sections summon Lissitzsky’s design for a booklet of Mayakovsky’s poetry. Typographic icons that indicate thematic categories are a stylistic nod to Bayer, but also draw on witty postmodern uses of associative ornament. For instance, the icon for an interview is a retro circa 1940s microphone.

The artists included in The Interventionists are an energetic and inclusive assortment, with women and minority artists represented in larger numbers than usual. Several are collaborative groups concerned with politics, such as the issues of identity, the workplace, and the governance of public space, health care, and homelessness. In addition to tackling the issues outside of aesthetics, much of the art consists of proposals to resituate cultural labor outside the gallery system and on the streets. Looking at the catalogue, one of my students explained to me that such “political art” was a “fad” of the 1990s that he was glad was “over,” a comment that crystallized my own appreciation for The Interventionists as an attempt to reclaim political art. The exhibition is an anomaly these days, when real war has dematerialized the “culture wars” over free speech and government funding for the arts. Some of the art is not new, such as Krzysztof Wodiczko’s Homeless Vehicle (1987-88). This shopping cart transformed into a shelter was called “political art” in the 80s. In The Interventionists the Homeless Vehicle now suffers the fate of being described as “interrogative design” for “urban nomads.” The latter is a peculiarly disconcerting euphemism that obscures the issues of class and race informing homelessness in America. The “art” that really awakens my students with fear, self-loathing, and compassion—AIDS activist-driven posters by Gran Fury—is absent from the catalogue. In the past, many of the artists included in the exhibition, such as the Chicago collective Haha, have tackled AIDS, but the absence of the issue seemed to confirm my student’s assumption that the crisis was someone else’s other than his, a piece of a prior decade. To be fair, the curators seem to have consciously sought issues and expressions that cultivate dialogue instead of diatribe. Most of the artists work in more subtle and less confrontational ways, a trend that I see as being indicative of a widespread hesitation to forgo the umbrage of the fine-arts orientation, both by the artists and MassMoCA.

The use of “design” as a term to describe Wodiczko’s work pointed to a lack of clarity in the curators’ criteria. Why do the sculptural installations and performative works so squarely stay in the turf of “art” and not the expanded field of design? Surely there are commercial retailers who are producing goods worthy of inclusion in this show, whether they are t-shirts or bumper stickers. Instead of including DIY designs on sale on eBay and the Web, we get fairly arty examples of intervention. Inflatable housing units by Michael Rakowitz, Wodiczko’s student at MIT, that parasitically connect to HVAC exhaust systems, are beautiful for their sensation of transitory time and their efficiency of materials, but, simply to press the point, couldn’t the exhibition have strayed into the self-conscious commodity a bit more? The graphic works that are included, from the collections of stenciled and printed posters amassed by the God Bless Graffiti Coalition to Haha’s animated messages on taxis, are not especially convincing, at least as catalogue entries. Rubén Ortiz-Torres’s logos on baseball hats scramble the cultural identities of minority groups so that “Malcolm X” and “Mexico” are a new hybrid, but why and how these particular designs are more valid than others is unclear. Why not include really clever advertisements by MoveOn.org? Lucy Orta’s “body architecture” and Rakowitz’s work are notable for their success as sculpture and design. The two were recently featured by the Design Department in the Museum of Modern Art in the exhibition “SAFE: Design Takes on Risk” (2006). Whether such a confluence of selection reflects unanimity in what is “museum quality” or some other factor is worth pondering. Herbert Simon, computer scientist, has optimistically cast the meaning of the verb “design” as a broad to our lives as social, tool-wielding animals, in his opinion that “Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones.” In contrast, this catalogue chooses to frame its field of inquiry mostly as “art,” an odd decision if a confrontation with “everyday life” is what is sought.

The theoretical framework of the catalogue is more problematic than the individual art works because the essays fail to satisfyingly define “everyday life.” This might seem like an ill-advised request, the telltale sign of an academic writing from within the ivory tower, but is essential if artistic intervention is to be distinguished as “alternative.” In cities of insidiously commoditized environments, and with a Web full of indigestible amounts of information about personal lives, the differences between public and private space and “everyday life” and other space is confused. For instance, how can a reading group comprised of individuals, such as “16 Beaver” which meets in lower Manhattan, be differentiated as art apart from any of the many other reading groups across the world? I am not questioning their integrity but their “situational” position, and their designation in relation to the broader context. Is their address of Beaver Street in New York City a credential in “everyday life” or in the world of today’s art market? A more self-critical essay would have been helpful. Michel De Certeau’s The Practice of Everyday Life, published in 1984 (English translation 1988), is central text for Nato Thompson’s definition of art in relation to “everyday life.” Whereas the French philosopher was intent to frame individual autonomy and free-will in relation to hegemonic power structures, and created a binary opposition between an individual’s evasive “tactics” and societal “strategies,” Thompson uses the terms “tactics” and “strategies” to discuss how an artist might interface with “everyday life” so as to effect social change. He asserts that artists are no longer working in “isolated actions” but are now collectively promulgating their own “strategies” through multimedia connectivity. This extrapolation of the terms is not wholly convincing, for no artistic collaborative can establish the Foucauldian regime that De Certeau was trying to find a way to undermine. It is hard not to see artists as having a broadcast network that consists of anything more than sporadic and peripatetic tactics.

Sholette’s essay ruminates on whether there “can be revolutionary art without the revolution” (133). He suggests that Rodchenko’s slogan of “art into life” is being retooled by media-savvy artists, so that contemporary information-based work slides “art into business” (139). Again, the enigmatic lack of definition of “the everyday” hinders an understanding of what qualifies as “intervention” or “revolution.” Sholette uncritically sees early twentieth-century Modernist revolutionary artistic strategies as if the utopian strategies of the 1920s were not without their dark side. He also seems a bit too sure that twenty-first century “Interventionists” are continuing a long-standing legacy of counter-capitalist insurgency. His is an exuberantly optimistic diagnosis of the times.

Of course, this publication was not intended to be a scholarly argument about the “everyday” but to open a still recondite mode of making art up to a broader public. Sholette and Thompson have gathered much evidence that working outside the “white cube” of the gallery space still remains fertile ground. Perhaps only academics will care that Engels is misspelled as “Engles” (134); artists should care more than to spell “Suprematism” as “Supremitism” (137). It is a pity these errors linger in the catalogue’s second edition. As I watch colleagues assign the catalogue to their students, I cannot help but worry that arriving at a more rigorous theoretical definition of “everyday” using material culture would have provided a more disciplined argument. For that exhibition, other anonymous artifacts would have been required. These would have diluted “fine art” but more convincingly discussed what constitutes an intervention and/or the everyday.

The strength of Ann Reynolds’s Robert Smithson: Learning from New Jersey and Elsewhere is that she documents the full coarse stew of Smithson’s daily life as an engagement with science and pulp fiction, and his incorporation of the materials of mass culture into intellectually rarified spaces and places. An enigma is that the perspective of the professional art historian is still the primary text: we return to Clement Greenberg to work out the battles over “abstraction” and perception and the author assumes that Roger Corman’s 1963 work X: The Man With X-Ray Eyes is a simple narrative. This revision of a 1993 dissertation has not shed its origins as an academic debate. However, it is pleasantly atypical for work on Smithson because it bypasses Spiral Jetty (1970), Smithson’s earthwork that has become an icon of Post-minimalism and Postmodern art, in favor of a more expansive survey of projects.

The book takes its title from Learning from Las Vegas by Denise Scott Brown, Steven Izenour, and Robert Venturi, the 1972 architectural treatise that urged architects to reconsider the strip mall as a vernacular worthy of emulation. Reynolds’s second chapter which outlines Smithson’s use of New Jersey as an alternative space to Manhattan is the book’s major contribution to the ever-growing field of books on this artist. Like the architects, Smithson approved of the messiness of everyday life. By focusing on his work about New Jersey and basing her work upon ephemera in the archives, Reynolds’s book brings to life a more quotidian Smithson than prior scholarship. It also brings Smithson’s concept of “nature” down to earthly use. “The best sites for ‘earth art’,” wrote Smithson, “are sites that have been disrupted by industry, reckless urbanization, or nature’s own devastation” (Flam 1996, 165).

Smithson and his contemporary Gordon Matta-Clark have become heroic for pushing boundaries and forcing “art into life.” Because their lives ended prematurely, they are imbued with the glamour of James Dean in today’s art-world. Unlike many of their contemporaries, they look good because they never lived to become the decadently rich art-stars of the 1980s. Whereas the cult of Matta-Clark is built around contemporary fixations with rough and tumble urban decay and graffiti, Smithson’s groupies celebrate Spiral Jetty as a sublime encounter with an extreme environment. Paradoxically, every one of my students (and colleagues) who talk exuberantly about Spiral Jetty as a physical exploration of space know it as an aerial photograph. It is read safely from the confines of a proxy cockpit, and in that comfort we fool ourselves into thinking that we “get” it.

Drawing a morphological diagram between Smithson’s influences and work, Reynolds shows how his art was about very simple things: alienation from space, the failure inherent to methods of mapping, and the frisson between multiple mapping systems in verbal and visual perception. Reynolds lays out this information in a manner that prioritizes art historical intra-familial complexities. Chapter One is a rather tedious jaunt through the relevance of Clement Greenberg and other 1960s theories about vision. It sets a stage and stocks it with main characters—enantiomorphs, Robert Morris, and Ernst Gombrich—but is an academic tongue twister. Exemplum gratis regarding Smithson’s Alogons: “they are more sight-specific than site-specific, although the specificity of their site produces this sight-specificity” (28). This writing is the result of reading too much badly written art historical theory and Smithson himself. He liked to talk and write about “pointless vanishing points” and free-associate.

“From the shiny chrome diners to glass windows of shopping centers, a sense of the crystalline prevails,” Smithson rhapsodized, seeing in the surfaces “an infinite number of reflected ready-mades.” This kaleidoscope of references romantically blurs art and life, or transmutes art into life. Growing up in Clifton and Rutherford, New Jersey and attending the Art Students League in New York City, Smithson’s concept of culture in society early on was based on a relationship of center and periphery. He never went to college, becoming a member of contemporary downtown art scene at a very young age. His entire oeuvre was made between ages 22 and 35, a fact that explains the degree to which his work smacks of adolescent sci-fi thrillers and drug-induced escapades. Peter Schjeldahl (2005) and others have noted that his writings have the rhythmic cadences and hallucinogenic power of Beat poetry, and that these have served as his legacy better than most of his visual work.

The tendency towards complexity and pseudo-scientific jargon in Smithson’s texts obscure their simplicity. His search for cultural “elsewheres” to question the art gallery led him to seek out marginal spaces between culture and industrial waste or between industrial waste and nature. His 1967 “Guide to the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey” fetishizes industrial margins. It is a bizarre anti-modernist future past where antiquated machines resembled dinosaur fossils. Reynolds conveys Smithson’s delight in the decay of American highway culture. She also explains the importance of Smithson’s development of the “Non-Site,” a delineation of spatial coordinates that is self-consciously unresponsive to the outer world. This rationalization enabled him to keep making work for galleries when he was becoming a poster-boy for earthworks. Enigmatically, I find that the “Non-Site” refutes the centrality of Manhattan more than it points towards anywhere else. Whereas his work in the Pine Barrens of New Jersey carries the emotional charge of meta-autobiography, Smithson’s “Non-Site” was simply not-Manhattan. The “Non-Site” begs the question of whether Smithson’s site-specific work, like going to Passaic, was really ever about the “everyday stuff” of New Jersey. Unlike Venturi, Smithson did not really “learn” from New Jersey. He was committed to estrangement, stating “Things-in-themselves are merely illusions” (222). Displacement is both the modus operandi and the message of Smithson’s work.

Reynolds’s archival work reclaims the diurnal Smithson, and this endeavor makes the book without equal in its field. She notes that the artist’s pediatrician was the famous poet William Carlos Williams, and that his own celebration of New Jersey’s mundane modernity and his use of geographic and popular imagery surely inspired Smithson. Williams’s line that “there are no ideas but in things” prodded Smithson to photograph the set-back architecture of Art-Deco Manhattan and to perceive a child’s sand box as an image about the “illusion of control over modernity.” As often as he was brilliant, Smithson was wildly sophomoric. The sand box was a “map of disintegration” and also “an open grave that children cheerfully play in.” His intellectualization of the banal articulates his own childless status more than any other meaningful fact or fiction.

Dissecting his reading and cataloguing his library, Reynolds connects his references to Bataille, Lévi-Strauss, and others to a cultural logic specific to his 1960s context. Sifting through the enormous archives, Reynolds astutely observes that Smithson could scrawl art jargon on the cover of LIFE magazine that depicted the aftermath of the Newark race riots, the representation of a limp and crumpled up body of an African-American child. Unlike Williams, Smithson lacked empathy and sympathy for people in addition to things.

The trouble with delving so deep into the archives, and Smithson’s photocollages of pornography, is that the reader loses sight of whether the artist was representative of any particular issue, style, or idea. His penchant to auto-archive is not compared to Warhol, and the issue of Pop art is oddly absent. Was its influence confined to private collages by Smithson? Her explicit assumption that Smithson made “counterculture” (xvi) is another disturbing aspect of the book. How can this determination be made?

Drawing a line between where the production and reception of art becomes subversive or taboo is increasingly difficult. Operating outside the gallery or on the Web does not necessarily gesture at a public space. Trying to design a functional commodity is seen as subversive in many art schools. The authors of The Interventionists seek to destabilize assumptions and run against the grain of American society, and to their credit they have done so in a manner that is provocative rather than preachy. However, at a time when there is little intellectual real estate that seems to be truly counter-cultural, the intention seems difficult to measure and important to qualify. Problematically, what is theorized in most circles of “fine art” as “everyday stuff” is a foil to play against established points of art and power. “Everyday life” is not a universal substrate but defined by culture, class, ethnicity, gender, etc. Taking material culture more seriously would have made the very different arguments of these texts more convincing. With luck, students who are assigned these texts will demand a greater definition of this terminology.

References Cited

Flam, J. 1996. Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Schjeldahl, P. 2005. “What On Earth: A Robert Smithson Retrospective.” The New Yorker, http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2005/09/05/050905craw_artworld, last accessed 24 May 2007.