On the Road

Odds and Ends in Material Culture

by Wayne Brew, Montgomery County Community College

I am not a collector, but my father was. With a last name of Brew you could easily imagine that my father collected beer items, including cans, trays, tap-knobs, and patches. Over the years my father filled the basement with these items. I, on the other hand, am not a collector, so some difficult decisions had to be made when it came time for my parents to move to an apartment. After some negotiations I convinced my father to sell off the cans, beer tap-knobs, and pennies (he had a huge collection of wheat-back pennies). In return I would store the beer trays for him. They are now cluttering the crawl space of my basement.

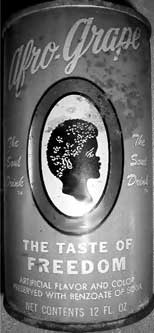

I did keep some of the cans that had special meaning—for instance, ones with the word “Brew” on the label—or had some historic value, such as those with cone tops. But my favorite is a soft-drink can: Afro-Grape, the taste of freedom (the soul drink). This is a great example of material culture as a time capsule that tells a story and reflects social history.

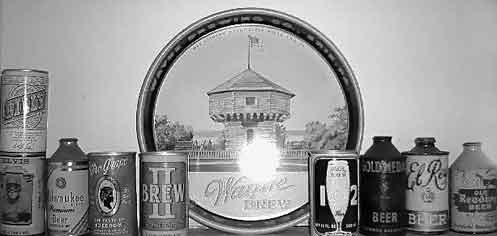

Figure 1. The display of my favorite cans (and of course anyone would like their name on a beer tray). The Afro-Grape Can is the third form the left (see detailed photo below). The beer tray is from the Wayne Brewing Company which was located in Erie, Pennsylvania. I would like to think that the brewery was named after me or that I was named after a brewery. Neither is true; the brewery was named after “Mad” Anthony Wayne.

Figure 2. A closer look at the Afro-Grape Can. It is a deep purple in color and contains the captions “The Taste of Freedom” and “The Soul Drink.”

Recently I Googled Afro-Grape to find out more. The only direct link I found was a web page for attorney Tom Devine. Among Devine’s many business ventures, in 1970 he partnered with others to form the Afro-American Distribution Company. They produced three sodas that were distributed the New York City Metro Area: Afro-Grape, Afro-Orange, and Afro-Cola.

I contacted Mr. Devine, who now lives in Houston, Texas. The first thing he wanted to know was how I associated him with Afro-Grape (I guess he never read that part of his web page). He went on to relate in his email reply to me that he once had all three cans, but they were stolen by a cleaning person. He kindly offered, “I wish I still had my cans and I would be delighted to give them to you. These products were sold in the Big Apple, Sloans, and Safeway grocery stores in the New York Area.”

This can is a great example of how material culture captures a moment in time. I can not imagine a product like this being offered now; it may even be offensive to some.

Soap Lake, Washington

by Ralph K. Allen, Jr.

Prior to World War II, Soap Lake, Washington was a premiere spa destination for many who sought “the healing waters” which gave the lake its name and reputation. Originally utilized as a ceremonial, camping, and camus root gathering spot by Native American tribes, the lake’s peculiar chemical composition (only three lakes worldwide are similar) provided relief for a number of circulatory and skin disorders.

As the lake’s reputation grew, during the summer especially, trains would bring tourists and relief-seekers to the various sanitariums, hotels, and cottages which were rented out on a daily, weekly, and monthly basis. The cottage districts (a function of location and early merging of three villages into the current city of Soap Lake) contained small, often one-room units which remain in various stages of reconstruction or disrepair today.

Figures 1-2. The Soap Lake Inn, formerly Thorson’s Soap Lake Resort and home of Thorson’s Soap Lake Products, estimated construction date 1905. Photographs by Ralph K. Allen, Jr.

Figure 3. The entrance sign to Soap Lake, showing the “healing waters” slogan.

Figure 4. Typical cottage, circa 1905-30.

Of the big resorts, replete with boardwalks, on-site soaking tubs, access to the beachfront and other pleasantries, the Soap Lake Inn currently stands out as a signature resort hotel dating back to original construction at the turn of the century. The building was constructed of round water-worn stones gathered locally by a real estate promoter named E Paul Janes. After his departure for Europe on a business trip he never returned. The building became well -known as a result of an enterprising woman’s, Roxy Thorson, penchant for mixing the mud from the lake into a series of balms, salves, and ointments as well as distilling the salts from the lake and selling the products as Thorson’s Soap lake Products.

After World War I, a U.S. Army private from nearby Wilbur, Washington, came to Soap Lake in search of a cure for Buergher’s Disease. Over time, McKay’s condition improved and he was able to resume full use of his legs. His respite from the disease, coupled with efforts of the American Legion, local and state politicians, resulted in the development of the McKay Research Institute which became, officially, McKay Memorial Hospital in 1938. McKay had come to Soap Lake to live only an expected three-months but survived for seventeen years, bringing his message of healing to a growing number of veterans and others seeking relief from a number of other diseases.

Figure 5. Typical cottage with local stone, circa 1905-1930.

Figure 6. Members of the Colville Confederated Tribes at the celebration of the Healing Waters Sundial, 2009.

Figure 7. The Healing Waters Sundial, the world’s first human-statued sundial, at Soap Lake. The figure’s feathers point North and basalt columns around the face designate the hours.

Today, the hospital building shelters a nursing facility, with samples of the lake water and mud in its basement after numerous studies of its chemical composition have been conducted.

The city fell into decline after World War II and the subsequent mass usage of modern medicines and techniques. Many still come to Soap Lake, however as a vacation spot to soak in the mud and drink its water but the glamour days of Soap Lake are fading into historical memory even as the city wrestles with the problems and prospects as an undeveloped tourist center on an off-beaten path in north-central Washington State.