The Baroque Parapet: Cultural Diffusion and the Sense of Place in the American Southwest

Marshall S. McLennan, Eastern Michigan University

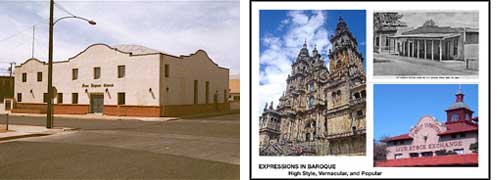

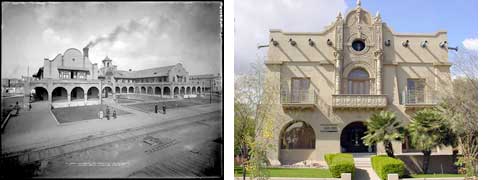

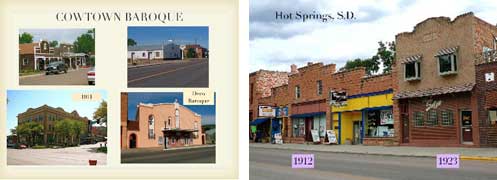

An architectural feature lending flavor to the regional sense of place in the American Southwest is the Spanish-derived baroque parapet (figure 1). This paper traces, through the twin processes of diffusion and simplification, how the baroque parapet with a curvilinear or stepped gable devolved from the high-style rococo-baroque cathedrals of late seventeenth- and mid-eighteenth-century Spain (image on the left in figure 2) to simplified, minimal vernacular baroque parapets, which characterized the nineteenth-century American Southwest ( figure 1; upper right image in figure 2). Early twentieth-century revival styles reinvigorated use of the baroque parapet. At the same time, in the context of popular architectural fashion, the Southwest-style baroque parapet migrated northward throughout ranching country, where it is sometimes referred to as “cowtown baroque” (lower right image in figure 2).

Figures 1 and 2. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

In Spain baroque architectural expression reached an emotional peak in the hands of the Churriguera family between 1680 and 1760, where it was characterized by extravagant, intricate foliated sculptural surface decoration known as “Churrigueresque.” In figure 2 we see one of the finest Spanish examples of the style, the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral. For purposes of this paper, however, we are more interested in the morphological characteristics of the Spanish baroque parapet than in the decorative details. The Iglesia Castrense de Madrid provides an example of an uncluttered baroque parapet and central gable for examination (figure 3). The gable is curvilinear and, in this instance, contains a bell niche. Another common feature of the baroque parapet is that it terminates at the building corners with some sort of elevated architectural detail. In this example, pedestals, comprising extensions of corner pilasters, support urns.

Figures 3 and 4. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

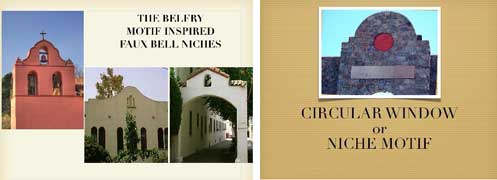

When the cathedral or church lacks a bell tower, a bell screen is usually integrated into the parapet gable. Such an integrated parapet facade is called an espadaña. In the baroque idiom it is usually curved, often in a stepped or tiered manner and has one or more bell niches (figure 4). Another common parapet feature comprises projecting corner ornaments, which take a variety of forms from simple finials or urns to small shoulders, pedestals, pillars, cones, turrets, or corner crenellations (merlones) (figures 4 and 5).

Figures 5 and 6. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

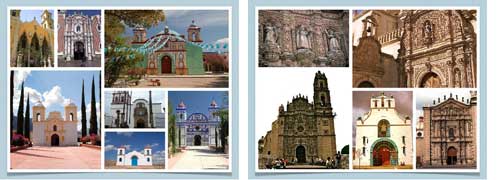

The late 1600s saw the Churrigueresque rococo-baroque style take root in Mexico (figure 6). However, Churrigueresque base-relief ornamentation began to lose favor in the latter part of the eighteenth century. This decline in use of intricate base-relief exterior wall surfaces can be viewed as the first step in design simplification. Mexican church builders turned to using flat stucco exterior wall surfaces. They nevertheless continued to adhere to the morphological basics of baroque design while incorporating Native American and Moorish decorative elements. Mexican churches became even more aesthetically florid and colorful than in Spain. This stylistic tradition continues into the present, and is often referred to as “Mexican baroque” (figure 7). The parapet gable frequently contains one or more statuary niches, perhaps a circular decorative feature, and, sometimes, a belfry or bell screen (figure 8). Finally, a series of finials, urns, pinnacles or similar raised objects usually stand upon the parapet cap (figure 9).

Figures 7 and 8. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

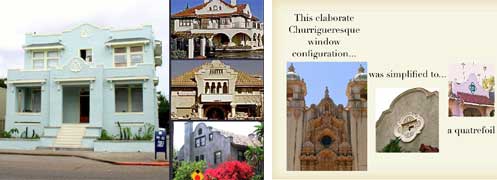

Although not part of the actual parapet, we should also take note of the choir window in the central facade of Mexican baroque churches of the colonial period. The choir window, located along the central vertical axis of the façade, took one of several shapes. Three designs, an oval; a hexagon, sometimes attenuated; and a lobed floral mouth (figure 10), shaped as a combined quatrefoil and star (Pierson 1976, 197), once reformatted and relocated into the parapet gable, became important features in the early twentieth-century development of the baroque parapet gable in the American West.

Figures 9 and 10. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

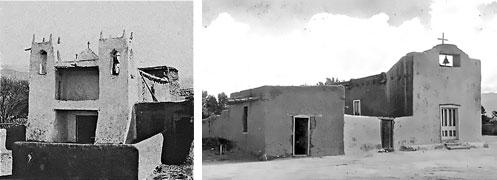

Just as the Church was the instrument by which baroque architectural design was carried from Spain to Mexico, events played out in similar fashion in what was to become the American Southwest. The priests who supervised the construction of mission churches in New Mexico, West Texas, Arizona, and California brought with them mental images of baroque design, but by necessity, they needed to rely upon local Indian habits of construction. Except in California, most of the earliest mission churches have not survived, but there is evidence that second and third generation churches built in the eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries usually emulated if not imitated the morphology of their predecessors.

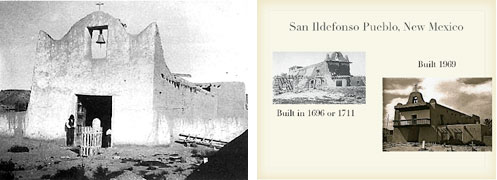

The Franciscans established a mission at Tesuque Pueblo, New Mexico, in 1598. The mission church depicted in figure 11 was built before 1750, replacing an earlier church, but collapsed in 1880. It possessed a stepped parapet gable situated between twin bell towers. Although exceedingly simple, its execution remained true to the baroque parameters of its progenitors. The replacement church, constructed in the 1880s, lacks bell towers, but has a bell screen embedded in the shallowly stepped and rounded central gable, the motif called an espadaña (figure 12). Both parapet gable examples are elemental offspring of baroque progenitors.

Figures 11 and 12. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

The next example, also from New Mexico, is the Sta. Clara Pueblo church, built in 1758 to replace an earlier structure (figure 13). This photo was taken in 1899, six years before the church collapsed under the weight of a new roof. It had a central espadaña, and, instead of church towers, corner pinnacles. It is a clear vernacular expression of folk simplification.

Figures 13 and 14. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

Figures 15 and 16. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

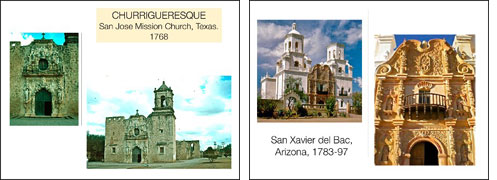

The mission church at San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico also illustrates design continuity in successor churches (figure 14). Churrigueresque decorative elements gained only a minimal foothold among the missions of Mexico’s northern frontier. The two best examples are the San Jose mission church outside San Antonio, Texas, built in 1768 (figure 15), and San Xavier de Bac, erected in the 1790s near Tucson, Arizona (figure 16).

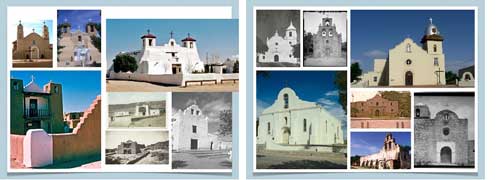

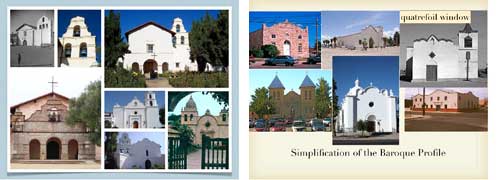

Other examples of Spanish missions incorporating elements of baroque central gable and parapet design for New Mexico, Texas, and California are illustrated in figures 17, 18 and 19 respectively. Unique to California were the use of bell walls or campaniles. Two examples, Mission Santa Ines and San Juan Bautista, are included in figure 19. Also note in figure 19 that the choir window of the Mission San Carlos Borromeo provides an example of the lobed floral mouth motif.

Figures 17 and 18. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

Figures 19 and 20. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

Even after the Southwest territories and California, were acquired by the United States, many local churches continued to be designed utilizing a simplified baroque idiom in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Commonly use of a bell screen was dispensed with in favor of a curvilinear parapet gable, which in Texas is frequently called an “alamo parapet” (figure 20). Another development was the reconfiguring of the attenuated hexagonal and lobed floral mouth choir window into a quatrefoil design. An example is seen below the statuary niche of the Doña Ana church, upper right in figure 20, erected in Las Cruces, New Mexico, around 1850.

In figure 21 we see a chapel in Terlingua, Texas, in which the architectural form is so basic that the Spanish baroque idiom is evoked only by a belfry minimally curvilinear in form.

Figures 21 and 22. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

The baroque parapet roof profile was not limited to religious structures. During the nineteenth century, it also appeared, in vernacular form, on secular buildings. A cantina since 1934, El Patio is one of the most historic buildings in La Mesilla, New Mexico. This adobe structure was erected in 1854, and between 1858 and 1860 housed the local headquarters of the Butterfield Overland Stage Company, which operated a stage route between St. Louis and San Francisco (figure 22). The parapet, with its rounded faux bell screen and corner crenellations, is designed in the tradition of an espadaña, but here is expressed as a simple vernacularized folk baroque parapet.

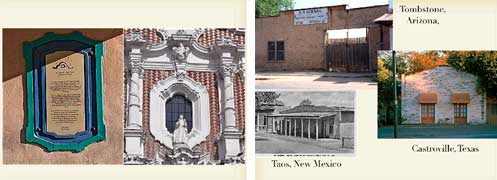

Even the historic plaque on the cantina wall emulates a common baroque choir window form (figure 23). Use of a symbolic bell screen on a secular building is unusual before the Mission style emerged early in the twentieth century. Although this building dates to the mid-nineteenth century, the espadaña motif may be a later contrivance.

Figures 23 and 24. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

Other examples of nineteenth-century secular buildings bearing vernacular baroque parapets are illustrated in figure 24. The Kit Carson adobe (built in 1825), lower left as illustrated in an early twentieth-century postcard, features a shallow curvilinear parapet. (The parapet has subsequently been modified by the U.S. Park Service into an even gentler set of steps than portrayed in the above illustration.) Conversely, the Castroville building retains corner pillars but utilizes a raking angle capped by a flat apex to the parapet, and the O. K. Corral employs only a simple flat-stepped parapet. In Europe the use of flat-stepped parapets predates the emergence of the baroque style, however, in the Southwest it can be interpreted as a vernacular or folk remnant of the baroque architectural idiom. In a number of cultural traditions the circle symbolizes perfection and the square, in turn, stands in as a simplification of the circle. Similarly, in the Southwest, in the process of folk simplification, a square-stepped parapet, with its greater ease of construction, frequently has been substituted for a baroque curvilinear stepped parapet.

These examples attest that in the frontier Southwest the high-style baroque gable and parapet of Spain and the Mexican heartland was vernacularized and reduced to the simplest expressions of its elemental forms, what we might term, “folk baroque.” The rounded or stepped roof profiles stand in strong contrast to the peaked gables characteristic of Anglo material culture traditions in much of the United States, and, together with flat-roof ranch and pueblo style buildings, they convey to the Southwest a distinct sense of place.

However, this is not the end of the story. When the colonial revival movement swept into architectural fashion in the United States beginning in the 1890s, the region stretching from California to West Texas turned to its own distinct colonial past and developed a style loosely based on provincial baroque frontier mission architecture. Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge’s design for Stanford University (1887-1891) is generally regarded as the starting point for the Mission Revival style, although it was blended with strong doses of Richardsonian Romanesque. Richardsonian influences were dispensed with in the design and construction of the Casteñada (1898), one of the first of the Harvey House railroad hotels. Its design was loosely based “on a provincial extension of the Spanish baroque culture” (Henry 1993, 141; figure 25).

Figures 25 and 26. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

Figures 27 and 28. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

With its curvilinear stepped central gable, the Owls Club mansion erected in Tucson, Arizona in 1901-2 is very much an ambitious example of the new Mission style, and even features a faux Churrigueresque retablo frontispiece (figure 26). Initially, large homes predominated, and established the parameters of the Mission style (figure 27).

Three window and niche configurations became emblematic of the style, the quatrefoil, the bell niche, and the circle (figures 28, 29, and 30). A three-bell triangle motif became particularly popular.

Figures 29 and 30. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

The Mission and closely related Spanish and Mediterranean styles quickly filtered down the social scale to middle class housing, once again revealing a process of morphological simplification. The examples are from Arizona and California (figure 31). They display a diversity of gable configurations, but all have “corner bump-ups” emulating the pedestals and crenellations of the past.

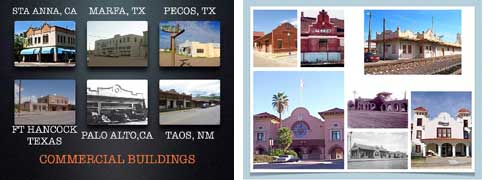

During the early twentieth century, the baroque parapet also was used extensively in commercial and public architecture executed in the Mission or other related styles. It lends a degree of architectural interest and even monumentality to these buildings. In the Southwest the baroque parapet continues to be utilized to the present day because it is associated with the regional cultural landscape and sense of place.

Figures 31 and 32. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

Figure 32 provides glimpses of Mission-baroque style stores and theaters in Silver City, New Mexico, and Marfa, Texas. The theater in Silver Springs has two baroque parapets superimposed upon an otherwise neo-pueblo style building, while the theater in Marfa flavors the baroque parapet with an Art Deco zest. The Brite Building in Marfa, Texas, illustrated upper-center in figure 33, is in a Pueblo-Deco style, but is capped by a stylized stepped parapet, which in the Southwest can be attributed to the regional Spanish baroque tradition.

Figures 33 and 34. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

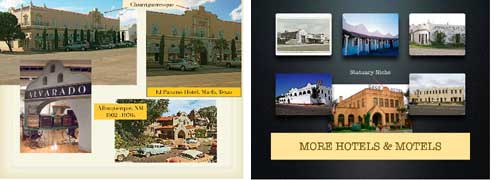

The railroads played an early and important roll in popularizing the Mission style and its Spanish baroque mannerisms (figure 34). Many of the Harvey House railroad hotels, in addition to the aforementioned Casteñada, were designed in the Mission style. Among these was the famous Alvarado Hotel in Albuquerque, demolished in the 1970s, seen lower right in figure 35. The arched central gable has been preserved in the Albuquerque Museum.

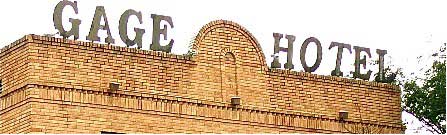

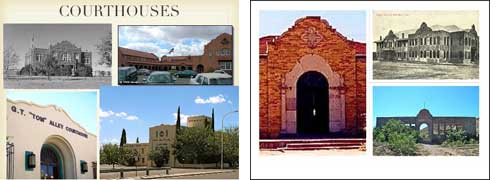

Some hotels like the Trost and Trost-designed El Paisano (1930) in Marfa reached back to the more complex Churrigueresque baroque designs of the Mexican heartland for their inspiration (see figure 35). Another Trost and Trost hotel, The Gage (1927) in Marathon, Texas (figure 36), is conceptually subtle in its stylistic allegiance, but the faux statuary niche in the rounded parapet gable makes its case (figure 37). Many public buildings such as courthouses (figure 38) and schools (figure 39) constructed during the early decades of the twentieth century also utilized the Mission style. Banks, office buildings, libraries, warehouses, and gas stations also were designed in the Mission baroque style.

Figures 35 and 36. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

Figure 37. Mission-style baroque parapet with faux statuary niche, Gage Hotel, Marathon, Texas (courtesy the author).

Figures 38 and 39. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

Is the Mission style with the baroque gable and parapet confined to the Southwest (and Florida)? No. But, elsewhere in the U.S. its appearance is as an exotic, with one regional exception. Wherever cattle ranching spread, to the High Plains, the Black Hills, and the Rocky Mountains, a sense of attachment to cowboy culture took root and was mythologized. The main streets of nineteenth-century western frontier towns were originally populated by false-front structures. If these buildings possessed any stylistic details, it was Italianate bracketed cornices, not Spanish baroque parapets.

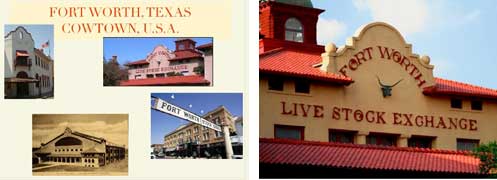

The twentieth century, however, saw the main streets of this region enthusiastically embrace Mission-style facades as iconic statements of their Western ranching heritage. Just as Spanish baroque parapets had long been associated with Hispanic folk culture in the Southwest, at the beginning of the twentieth century, they were embraced within the popular culture of Western ranching country (Henry, 148). To quote Carla Davidson, writing about turn of the twentieth century Fort Worth, Texas, and its association with historic cattle drives, “flaunting a style variously called Cowtown Baroque, Mission, or Spanish Revival, all these buildings have a presence and an aura that goes beyond their homely functions. Their parapets, bell towers, cupolas, shaded verandas, red tile roofs, and graceful railings, their height and breadth and airy interior spaces, seem to express perfectly the pride that drove Fort Worth at just that time and place” (Davidson 1990).

It might be argued that Fort Worth, self-labeled as “Cowtown, U.S.A.,” is the nexus through which Southwestern Spanish baroque was recast as “cowtown baroque” (figure 40). The earliest structure built to facilitate the Fort Worth stockyards was the Livestock Exchange, erected in 1902 in the Mission-Revival style. The symbolic linkage between Spanish baroque architecture and cowboy culture was achieved by the placing of a Texas longhorn bust in the Mission-style baroque gable over the entry to the Fort Worth Live Stock Exchange building (figure 41).

Figures 40 and 41. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

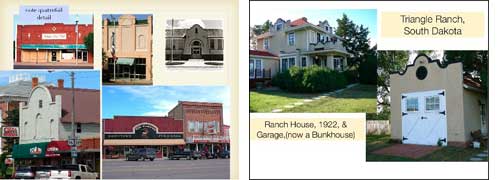

Some commercial examples of Mission style or Cowtown Baroque in the American West lying outside the true Southwest are illustrated in figures 42, 43, and 44. In several instances the only feature suggesting a derivative relationship from a regional baroque heritage is a stepped parapet. In figure 43 the two commercial buildings with their angular parapet profiles probably have less of a derivative relationship to Mission Revival than to late nineteenth-century folk baroque. The Elk Canyon Downtown Pub and Grill, illustrated lower right in figure 44, captures the expedient fabricated appearance of a late twentieth-century cowtown-baroque facade. The roofline comprises a simple one-step parapet, while the commercial sign is formulated as a curved central gable. In a real sense what we are seeing here is faux baroque.

Figures 42 and 43. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

Figures 44 and 45. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

Homes were also designed and built in the Mission-Revival style throughout the rangelands during the early decades of the twentieth century. The Triangle Ranch farmhouse in Jackson County, South Dakota, which replaced the original log cabin homestead, is exemplary. Basically a foursquare built in 1922, it is the Alhambra model from a 1917 Sears catalog. It came with an accompanying bunkhouse, originally a garage, also in the Mission-Revival style (figure 45). Even the circular vent in the bunkhouse gable is derived from the Spanish baroque vocabulary.

Two other examples are taken from Durango, Colorado, a Mission- Revival design making sophisticated use of statuary niches (figure 46), and from Buffalo, South Dakota, possessed of a fine baroque parapet complemented by simple recessed diamond panels (figure 47).

Figures 46 and 47. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

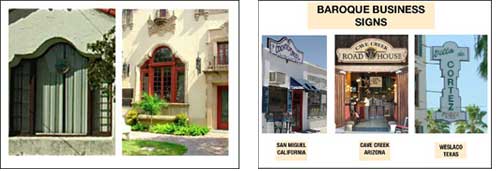

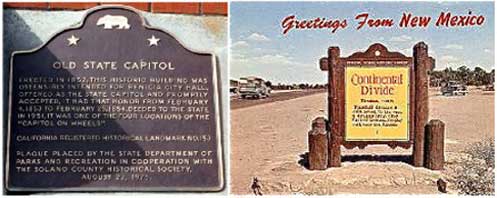

Some ancillary architectural and landscape features also acknowledge the Southwest’s baroque heritage. Window voids occasionally ape the outline of a baroque parapet (figure 48). Or, as with the Elk Canyon Pub and Grill, signage may emulate the curvilinear profile of a baroque parapet (figures 44 and 49). In California state historic markers use the baroque profile, as is also the case with some highway signs in New Mexico (figure 50). Finally, it would be difficult to overlook that the baroque parapet gable with bell screen has been appropriated as a franchise logo by Taco Bell.

Figures 48 and 49. Select either image for a larger view and more information.

Figure 50.California State Historic Site marker (courtesy www.hmdb.org, Syd Whittle, photographer) and a New Mexico informational highway sign on a vintage postcard.

Summation

In tracing the journey of the baroque parapet and gable from seventeenth-century Spain through Mexico to the American Southwest and the broader regional sphere of cattle country, we can observe the playing out of two cultural processes, vernacularization and simplification in architectural practice. Churrigueresque, an elaborately decorative version of rococo baroque church architecture, was carried from Spain to Mexico during the second half of the seventeenth century. The first step in simplification was one of façade ornamentation. By the late eighteenth century, the use of Churrigueresque façade detailing was in decline in Mexico, replaced in preference by smooth stucco or tile walls. The sophistication of construction and the baroque façade profile of the earlier churches, however, were both retained.

With few exceptions the mission churches established on the northern frontier were more rudimentary in scale and construction and features like the bell towers, espadañas, parapet crenellations and pinnacles were more crudely executed than in Mexico’s heartland. Only in a few instances was Churrigueresque appliqué employed on a mission church exterior, and in those instances was limited to the retablo area of the façade. In the urban villages of the nineteenth-century Southwest, simple baroque-derived but vernacularly expressed stepped or curved parapets made the transition to secular buildings.

The Southwest, including California, is a transition zone between two culture regions, Hispanic and American. Historically it has been a zone of cultural encroachment of the latter upon the former, although initially nineteenth-century American immigrants to the Southwest found that their material culture was, in many ways, maladaptive to the arid environment. Consequently, many American landholders learned the ways of cattle ranching from their Hispanic neighbors. In architectural terms a slow symbiosis unfolded during the second half of the nineteenth century, giving rise to the “Territorial style,” encompassing climatically preadapted Hispanic building practices with American stylistic flourishes.

When the colonial revival architectural fashion swept the United States at the turn of the twentieth century, Americans living in the Southwest found romantic inspiration in the region’s Hispanic past. The baroque architectural idiom was resurrected from its vernacular slumber with the emergence of the Mission-revival style. Given impetus by high-style designs for railroad stations and hotels, and a variety of public and commercial buildings, the Mission style quickly became a fashionable choice for the homes of upper class Anglo-American and Hispanic citizens (figure 52). The Mission style and the baroque idiom soon permeated down to middle class dwellings, main-street commercial establishments, and as travel by automobile grew, to the motels and gas stations of the Southwest.

Figure 52. Click for a larger view and more information.

During the decades preceding World War II, examples of the Mission style, with its baroque gable and parapet, materialized here and there throughout the country as exotic architectural expressions, but throughout the American West, beyond the Southwest itself, wherever the cattle industry was part of the local heritage, the mission style was embraced in the twentieth century as part of that heritage. And in truth, both Spanish baroque architectural forms and the cowboy cattle-ranching complex are Hispanic cultural intrusions within the American cultural fabric (Jordan 1993). So-called “cowtown baroque” ranges from self-conscious curvilinear gables in the tradition of Hispanic churches and missions to the more vernacular stepped gables derived from nineteenth-century secular folk-baroque buildings of the Southwest.

Finally, from World War II until the present, the baroque parapet and gable has often been simplified to a vernacular mannerism, to a profile, utilized as little more than a billboard or a token acknowledgement of regionalism and a romanticized past.

References Cited

Davidson, C. 1990. On the Fort Worth trail. AmericanHeritage.com, www.americanheritage.com/articles/magazine/ah/1990/1/1990_1_34.shtml, last accessed 14 September 2009.

Henry, J. C. 1993. Architecture in Texas, 1895-1945. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Jordan, T. G. 1993. North American Cattle-Ranching Frontiers (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1993).

Pierson, W. H., Jr. 1976. American Buildings and Their Architects: The Colonial and Neoclassical styles. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books.