Between Booms: the Commercial Identity and Heritage Tourism of Mineral Point, Wisconsin

Andrea Truitt, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities

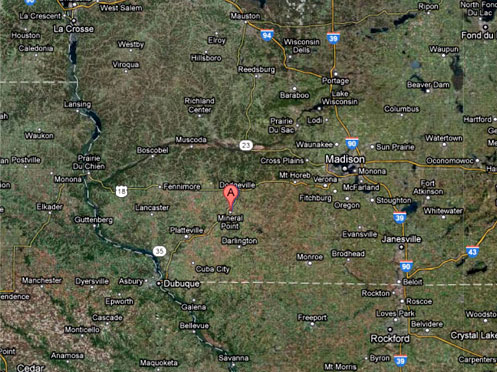

Although local and county histories make much of the lead and zinc-mining booms that occurred in and around Mineral Point, Wisconsin during the early- and late-nineteenth century, these booms were short lived (Figure 1). Between them, local histories refer to a period called the Middle Years, approximately 1849 to 1882, in which various forms of manufacturing failed to impact the economy as much as mining. Still, this period is important because the town adapted to changing circumstances by becoming a regional supply depot and trade center, thereby establishing a commercial, not mining, identity. It is this identity that continues to bolster the town through a different type of commerce, heritage tourism, which serves dual purposes depending on resident or tourist status.

Figure 1. Google map of Mineral Point, WI. The town sits one hour southwest of Madison, WI and two and a half hours southwest of Milwaukee. View this image larger.

Commerce, then, is a site in which we can interpret identity, heritage, and tourism, all of which dynamically interact together in Mineral Point. The town’s history provides an identity that allows it to comfortably enter into the economic enterprise of heritage tourism in order to sustain the town without creating a static environment that alienates its residents. Mineral Point is an exemplary place that takes advantage of the system of tourism by using its cultural resources which includes a commercial past. This naturalizes tourism so that it becomes a contemporary manifestation of the commercial heritage that already existed in the town beginning in the nineteenth century.

In 1971, Mineral Point became the first town in Wisconsin to have a designated historic district approved by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.1 This demonstrates the commitment that the town has to its cultural history, but maintaining the town as a historic district also opened up the use of heritage tourism as a source of income. An earlier effort beginning in 1935 also shows the pervasive role that commerce plays in identity formation. Residents Robert Neal and Edgar Hellum rehabilitated a group of stone cottages in order to preserve the Cornish heritage that initially shaped the town. Cornish immigrants began to settle in the lead region around 1835 because of their skill in deep mining, thus beginning Mineral Point’s ethnic and mining identity. Their stone masonry style was also adopted by the town and is seen in the numerous examples in the historic district. Neal and Hellum also ran a restaurant in one of the houses, serving Cornish food, notably the pasty. The site, known as Pendarvis, is now operated by the Wisconsin Historical Society, which shows the importance that Mineral Point has to not only regional history but to state history as one of the first settlements in the territory (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Curator Tamara Funk talking with Tom Carter in front of the Pendarvis Home. The historic site consists of the Pendarvis, Trelawny, and Polperro Houses, along with the Kiddleywink Pub and Martin Cabin. There is also a visitor’s center and gift shop. Photograph by the author.

Adapting and reshaping a place-based identity is a tense issue when marketing a place through heritage tourism, as historical identity can be heavily modified in the service of economics. Tourism may become a town’s main source of income, and the ability to package the town through its features, history, and identity is very important for survival.2 In order for it to succeed, many places create a generic historical experience similar to that of other locales, in order to market themselves to particular audiences that expect a recognizable narrative.3 Tourist towns sometimes face a paradox: in order to preserve a local identity, it simultaneously must transform into an easy-to-consume object.

New Glarus, a town 30 minutes east of Mineral Point, markets itself with a Swiss identity, based on the town’s original settlers. Its tourism literature insists that it is “America’s ‘Little Switzerland,’” and many of its commercial establishments push items associated with Switzerland, such as cheese and chocolate, and its architectural facades contain stereotypical Alpine elements such as half-timber, dark paneling, and Gothic-style sign typography. Its self-consciousness runs into excess, creating a seemingly disingenuous identity.

Mineral Point avoids much of this problem because of its successful adaptive reuse of buildings and services. Elements marketed to the tourists are the same marketed elsewhere: specialty shops, historic architecture, heritage festivals, art galleries, craft studios, restaurants, coffee shops, and bed and breakfasts.4 However, residents take part in these shops and events, making them a vital and meaningful part of the community. Other businesses necessary to the community reside amongst the specialty shops, including a doctor’s office, a pharmacy, and a post office, making parts of the historic district more useful to its residents than its visitors. Mineral Point has managed to integrate tourism, not surrender to it (Figures 3-4).

Figure 3. The Mineral Point Medical Center, High Street. Photograph by the author.

Figure 4. A building housing Auction Specialists, Inc. and All American Realty, LLC. Photograph by the author.

This balance creates a sustainable community that mindfully employs its past but has modified itself for a contemporary middle-class American lifestyle, saving it from kitsch through reuse and adaptation. This makes Mineral Point not a tourist town, but a vernacular town, with the agency to adapt and change over time, a place fully aware of its past and knowledge of the importance of its older structures to its identity and future.5 Most of the cultural content that is visible to the outsider visiting Mineral Point is the domestic and commercial architecture of the historic district, whose structures date from the mid- to late-nineteenth century. High Street and Commerce Street, the primary business streets, contain most of the shops (Figures 5-7). Because of this, Mineral Point can also be thought of as an “actively preserved heritage landscape,” defined by geographer Richard Francaviglia as a product of preservation legislation and an impetus to preserve the historic character.6 Key elements include buildings, historical sites, design integrity, and other features which demonstrate a place’s past.7 As with the writing of history, many factors, including local preference, local emphasis, and remaining artifacts contribute to the identity formed and what is actively preserved. Choice in preservation says a lot about what the town wants to remember about itself, and it is in architecture that we see the historic commercial identity of Mineral Point revealed.8

Figure 5. Google Map showing some of the current businesses on High and Commerce Streets. View this image larger.

Figure 6. Midway Bar, High Street. Down the block are the Atomic Ice Café and the Red Rooster Café. Photograph by the author.

Figure 7. Sitting outside of the Atomic Ice Café, the town’s coffee and ice cream shop. Photograph by the author.

In the time between the peak of the lead mining in 1848 and the full-scale operation of the Mineral Point Zinc Works, beginning in 1891, commerce took center stage as the town’s primary source of income, cementing its mercantile legacy. Lead mining’s apex in the region occurred just in time for news of the California Gold Rush.9 Mineral Point’s role changed with this news: instead of being a mining center, the community now served as a supply stop on the way west, and this brought temporary financial wellbeing.10 The town supplied everything that one could possibly need, including clothes, rifles, food, and tools.11 The Story of Mineral Point, published in 1941, laments this as a period of reduced circumstances.12 However, this was a fruitful and formative time that drastically shaped contemporary perceptions of Mineral Point. Advertisements placed by businesses during the gold rush demonstrate their desire to capture both the transient population and the local market. Shops declared their fidelity to community members by promising not to leave, all the while peddling goods suitable to the journey west.13 As men who traveled to California sent money back to their families, the commercial sector received much of it.14

Mineral Point’s economic legacy began in earnest in 1857 with railroad service coming to town.15 It allowed for more self-sufficiency and a move away from mining, and the town became “the shipping center and supply depot for a large and fertile farming land.”16 Throughout the nineteenth century an increasing connection to regional and national markets gave merchants more civic power and status, and the same could be said of Mineral Point, whose professionals, merchants, and tradesmen lived in homes that demonstrated their middle- and upper class status.17

Jail Alley, located one block north of High Street, contains three, two-story homes: the Kinney House, the Meadows House, and the Parley Eaton House, all constructed between 1846 and 1851, right at the beginning of the transformation from a mining town to a goods and services town (Figures 8-10). Professionals and tradesmen built and lived in all of them, using them as places of work in the case of the Parley Eaton House and the Meadows House, for a law office and tailor shop, respectively. All reflect a middle class lifestyle through size, building materials, and interior finish. For example, the Meadows House contains a built-cabinet and a fireplace with carved mantel, and decorative crown molding. Although the houses function differently and offer different services than the shops on High and Commerce Streets, they still function together to more fully illustrate the commercial history of Mineral Point.

Figure 8. A row of houses on Jail Alley. The Kinney House is in the center. Photograph by the author.

Figure 9. The Samuel Meadows House. Although the home appears small, it original façade on the other side is two stories. Photograph by the author.

Figure 10. The Parley Eaton House. Photograph by the author.

The decade between 1860 and 1870 experienced much growth, with businesses, homes, streets, and sidewalks constructed.18 Various industries came to town, including a flourmill, woolen factory, multiple breweries, a paper mill, and rubber plant, but none of them thrived for long.19 Although short-lived, the manufacturing sector cannot be excluded from Mineral Point’s history, as it, like tourism, is another manifestation of the town’s commercial history. An 1880 Sanborn map, along with subsequent maps, displays the diversity of High Street’s shops, which included grocers, milliners, clothiers, and a cigar shop, to name some (Figure 11). Interestingly, author George Bechtel marks 1915 as the peak year for commercial development.20 Although this is outside of the Middle Years’ range, the early twentieth century developments are crucial to the development of Mineral Point’s commercial identity as well, even when they ran parallel to zinc mining.

Figure 11. High Street, ca. 1915. Photograph courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society. WHI-37525.

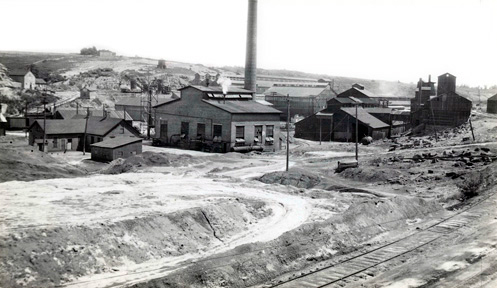

In the midst of the transition away from lead mining and to commerce, the first zinc furnace opened in 1860, and a decade later, zinc was the predominant ore mined from the area.21 Small-scale mining occurred throughout the Middle Years, although the depletion of easily extracted ore slowed the industry, which was supplanted by commerce. In 1882, the Mineral Point Zinc Company began operation. Created in 1891, the Mineral Point Zinc Works soon dominated the local zinc industry; it steadily increased manufacturing facilities, which included mines, smelting furnaces, and a sulfuric acid plant, built in 1899 (Figure 12). The site covered the land just south of town and across the creek. Even with a vast manufacturing operation, the mining only lasted until the late 1920s, when the Zinc Works only processed ore. Shortly after in 1935, the physical dismantling of the Zinc Works began.22 Today, no physical evidence of the mining tradition remains. The lack of visible trace on the landscape contrasts sharply with the written and visual record, which offers evidence of such a large-scale operation. It is the commercial buildings that remain, just as commerce has remained the town’s economic stronghold.

Figure 12. Zinc Works, ca. 1915. Photograph courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society. WHI-38320.

What is left is the commercial architecture of High and Commerce Streets, and the houses in proximity them, which also served as places of economic transaction. This is the history of Mineral Point chosen for preservation and presentation to the community and to outsiders. Without the past and current local business owners, which occupy many of the same buildings, this town would not thrive as it does. Architecture is vital to this history, allowing us to bear witness to the past and understand the role that middle-class shop owners and tradesmen played in sustaining the town and in creating its current identity. Shops have changed, and certain goods and services are no longer needed, but these buildings serve as evidence of the importance of the Middle Years, and they preserve the town’s legacy and identity for the future.

Notes

1 “Historic Downtown Mineral Point,” Mineral Point Chamber of Commerce website, http://mineralpoint.com/history/historic_downtown.html (accessed 3 December 2010). [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

2 Ibid. [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

3 Michael Hough, Out of Place: Restoring Regional Identity to the Regional Landscape (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 149. [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

4 “Art, Architecture, Ambience,” Mineral Point Chamber of Commerce website, http://mineralpoint.com/visitor_information/index.html (accessed 3 December 2010). [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

5 Hough, 157. [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

6 Francaviglia, 48. [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

7 Richard Francaviglia, “Selling Heritage Landscapes,” in Preserving Cultural Landscapes in America, ed. by Arnold R. Alanen and Robert Z. Melnick (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000), 45; “Art and Artists,” Mineral Point Chamber of Commerce website http://mineralpoint.com/art/index.html (accessed 3 December 2010). [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

8 Ibid., 67. [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

9 Writers’ Program of the Works Projects Administration of the State of Wisconsin, 1941. The Story of Mineral Point: 1827-1941. (Mineral Point: The Mineral Point Historical Society, 1979), 96. [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

10 Ibid., 96, 98. [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

11 Ibid., 98. [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

12 Ibid. [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

13 Ibid., 99. [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

14 Ibid., 104. [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

15 Ibid., 106. [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

16 Ibid., 106-107; George Bechtel, Would’ve, Could’ve Should’ve: A Sesquicentennial Story About Mineral Point, Wisconsin. Madison: The Associates, 1997), 9. [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

17 Clark, 29. [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

18 Bechtel, 129. [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

19 Ibid. 10-11, 71, 75-80. George and Robert M. Crawford, Memoirs of Iowa County, (Northwestern Historical Association, 1913), 203-204. [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

20 Bechtel, 149. [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

21 Story of Mineral Point [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

22 Ibid., 102. [RETURN TO ARTICLE]

Author Biography

Andrea Truitt is a Ph.D. student in the Art History Department at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities. This paper originated with fieldwork conducted for Anna Andrzejewski and Tom Carter’s ’s summer 2010 vernacular architecture field school, University of Wisconsin-Madison.