Indiscriminate Location: The Geography of Organic Farm Boundaries1

Terry A. Necciai, RA, Preservation Architect and Architectural Historian

The way farm boundaries have been shaped in Pennsylvania and adjoining states is a marker of material culture, settlement history, and agricultural heritage. The irregular-looking lines, seen especially in the southern half of Pennsylvania, developed in response to the hills and hollows that characterize a large portion of the state. Beyond a mere response to topography, they correspond closely to farm design, barn types, and agricultural trends. They reflect, for instance, how fields are laid out for pasturing sheep vs. cows. They were a logical way to divide land in preparation for laying out functional farms of the time, generally following the topography and in most cases, placing each farm in only one watershed. Within the bounds of each farm, the seemingly irregular lines relate to the way landscape features were arranged and connected together for functionality. They also reflect the typical scale and other characteristics of the state’s agricultural facilities in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as affected by cultural, historic, and farm management factors.

Figure 1: Original land boundaries within the Pequea Settlement area of Lancaster County. Penn sold some of the best land in large rectangular tracts before he died in 1718. Adjoining tracts were laid out later with boundaries based on ridges. The large rectangles were also later subdivided using less orthogonal lines. (Township Warrantee maps accessed online here.) View this image larger.

The legacy of organic lines used for farm tracts across southern Pennsylvania in the eighteenth century continues to affect how the landscape looks today. These boundaries and the patterns they produce, including the outer fields and inner working areas of farms, are important historical evidence and essential aspects of the character of the state. They should be part of what historians seek to identify and preservationists seek to preserve. The boundaries and other features that make up the physical layout of Pennsylvania farms contain rich information waiting to be unlocked, clues that frequently help in explaining how and why agricultural facilities from barns and springhouses to fences were located, designed, and built the way they were (Figure 1).

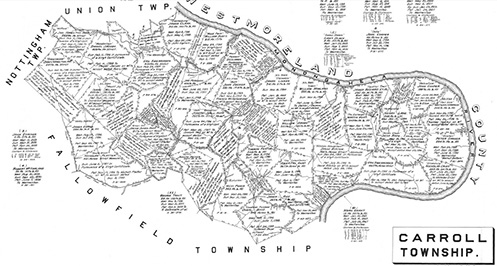

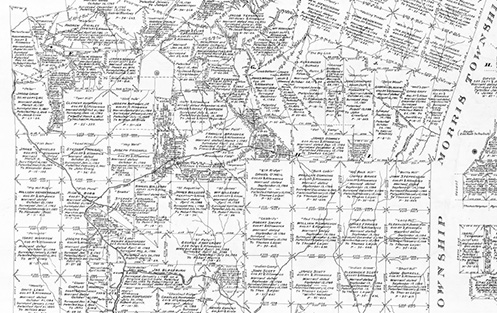

The southern half of Pennsylvania was almost entirely carved into land grants between 1680 and about 1820. The lines defining the original tracts were only rarely rectilinear, especially after ca.1720 (Figure 2). Land patents in rectilinear shapes tend to date from either before 1720 or after 1787. The largest rectilinear boundaries tend to be the earliest, as nearly level plateaus were divided into the first large speculative tracts granted by the Penns.2 Notably, these immense, nearly square tracts were carved into smaller farms along organic lines as they were subdivided. The initial property lines for any given area, whether orthogonal or free-form, were usually divided into manageable farms, often for three or four branches of the original family. Non-orthogonal geometry became more and more common as divisions were made, so that property maps of the southern half of the state increasingly resembled a crazy quilt until the trend changed in the 1780s (Figure 3). Following the natural lines of the topography, many of the farms were almost octagonal, often roughly shaped like a six-sided coffin, or sometimes a pentagon, an irregular trapezoid, a triangle, or some other polygon. After 1787, the use of rectilinear boundaries for land grants came back into vogue for the limited areas still available at the edges of the southern half of the state, as well as generally across the state’s Northern Tier.

Figure 2: The patent boundaries in Carroll Township, Washington County (above) are typical of farms across Pennsylvania. Here the river valley and small tributaries shape farms mostly settled in the 1760s. View this image larger.

Figure 3: The stark contrast between rectangular (south, east, and west) and free-form farms (center north area) marks the map (below) of land patents in Richhill and Gray Townships, Greene County (western edge of the county at the state’s southwest corner). The rectangular tracts are from the 1780s, likely speculative and/or tracts granted as military payments. The non-orthogonal lines are dated either 1780s or even later, in the 1800s, but may be pre-1780s settlements by families who secured their land titles later. View this image larger.

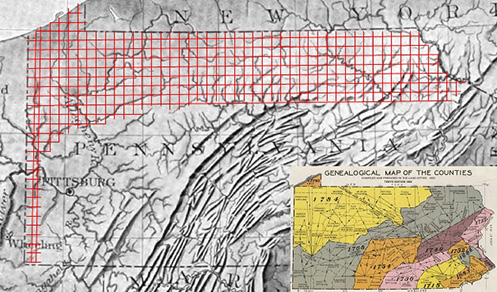

Land boundaries in Pennsylvania, thus, tend to fall into three periods. The first was when William Penn (1644-1718) was still alive. Penn employed a surveyor, and together they sold some of the most level land in expansive plains and plateaus, dividing it into large tracts, usually with rectilinear boundaries.3 By the time of Penn’s death, the Pennsylvania Land Office had descended into chaos. Settlers continued to lay claim to land, but the colony’s legal system for finalizing ownership remained dysfunctional until the land office was reorganized in 1732 (Klein and Hoogenboom) shortly after Lancaster County was formed. By that time, however, a new approach had evolved on the frontier, and the Pennsylvania government wisely accommodated it, as did the governments of several other states, notably Virginia. Settlement moved swiftly across southern Pennsylvania between ca.1730 and ca.1790. The population was growing and Pennsylvania purchased land in large swaths from the Native Americans and then redistributed it to settlers. By the end of the Revolution, the land available to settlers and investors was limited generally to the state’s western fringe, plus the northern half of the Commonwealth (Figure 4).

Figure 4: On the above relief map, lines have been added to show the areas where rectilinear farm boundaries were used on the majority of land grants after 1787. Though not all level, this area is beyond the larger mountains, closer to Lake Erie, and at the headwaters of rivers where the plateaus tend to be less eroded. The inset at the bottom right shows the areas Pennsylvania purchased from Native American tribes at different times. The grid pattern is in some of the last areas granted within land purchased between 1768 and 1792. (Larger base map from Relief Map of Northern Appalachians, U.S. Geological Survey, 1908. The inset map at the bottom right was prepared by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission in 1933 to illustrate the purchases and the formation of counties. Available online at: http://www.pabookstore.com/gemapofco.html .)

The use of rectilinear boundaries after 1787 was most likely influenced by a controversy that had unfolded nationally about how to divide land in what was to become Ohio. While Pennsylvania was still distributing tracts according to state-level policies, the land policies for Ohio were under the control of the new federal government. Thomas Scott, the congressman representing the southwestern corner of Pennsylvania fought the hardest to accommodate non-orthogonal farm boundaries in Ohio (Pattison). Some Virginians sided with him, but they were far outnumbered by representatives from states further north who were focused on New England’s interests.

The controversy was not rooted so much in the question of farm boundaries as it was in a concern about municipal government and the ideal form of democracy at the local level. New England’s representatives to Congress wanted to see New England style townships in Ohio. New Englanders had already begun to move to Ohio in groups, naming new settlements after the New England community from which the group had come.4 Pennsylvanians and Virginians, on the other hand, wanted settlers from their states to be able to go west one family at a time and select individual farms based on matching the land to the farm characteristics they understood, in accordance with the traditional land division methods used on the frontier as it had moved from the center of Pennsylvania across the Appalachian Mountains and associated plateaus and to the Carolinas, Kentucky, etc. The New England representatives, in their attempt to perpetuate their system, ridiculed the Pennsylvania-Virginia approach, labeling it “indiscriminate location.” The compromise was the Cartesian grid that developed for the Midwest in which a township was more a measurement of land, and not necessarily a community. The organic system of setting farm boundaries in Pennsylvania and Virginia thus got caught in the crossfire of this debate, and afterward, even Pennsylvania shifted back to using rectilinear boundaries.

In the frontier areas of Pennsylvania and Virginia,5 between 1718 and 1787, the custom was that the family interested in acquiring land went out in search of unclaimed territory, typically just west of the most recent areas to be settled. They selected a suitable site and began making improvements. They looked for a water source and preferably a meadow, (i.e., a small wetland or grassland clearing) 6 that could provide a readymade grazing area and hay source for their cows and sheep. They lived on the land in a log cabin or some other crude accommodation for as much of each year as they could, afraid to leave for fear someone else would lay claim to the land and the meager improvements they had made (Munger). Clearing a few acres, planting grain, and building a cabin were considered the first steps in retaining rights to a given parcel (Munger, Doddridge, Leyburn, Hoefling). On the frontier, these improvements were usually respected. It was taken as an unwritten law (Munger) that anyone who had made a sufficient dent in the forest had the right to retain the land they had chosen. The settlers would also mark trees, delineating the perimeter of what they felt was the appropriate domain around the spring and meadow they had chosen and/or the cabin or other buildings they had built. In general, settlers preferred to locate their houses just out of view of the nearest neighbors in each direction. This placed the farmsteads at a relatively uniform distance from one another. Most families selected a small valley (“or hollow”), or a section of a longer valley, delineating their land according to the topographic features. The watershed form usually funneled all water and activities down to the spring and meadow they had selected.

Ultimately, the settlers found ways to divide the land into tracts that contained between 100 and 400 acres. An amazing number of land claims settled in at about 300 to 400 acres. Pennsylvania codified these numbers into their land claim laws, some years allowing only 300 acres, and in other years, allowing 400 (Bioren, Harper, Fletcher, Leyburn). In those rare areas where no one seemed to want the surrounding land, the occupant of the initial farm was allowed to lay claim to up to 1,000 more acres.

The settlers understood that acreage was not just an abstract measurement of land area. The concept of an acre had evolved in various cultures as a measurement of one day’s work with a team of oxen and a plow.7 A surprising number of land claims on the frontier consisted of 365 acres or a very close number.8 Some literature indicates that settlers felt that 300-400 acres, or approximately one acre per day per year, was all one family had a natural right to claim (Hall). In Virginia, settlers were allowed much larger claims.9 However, the Virginia system also went hand-in-hand with slavery.

In truth, a family primarily raising grain and a few animals could not clear or manage 365 acres in a single generation. But many families divided the land among three or four sons. The result was farms averaging around 100-120 acres. Land was cleared at a pace of one to two acres per year. By the 1850s when the majority of the land had been cleared, 120 acres represented a manageable farm for a medium-sized family. About one third of the acreage was planted each year in crops, while some fields were rotated into pasture, hay, and/or green manure, and some of the acreage remained in woods or other uses. On a farm of 120 acres, the amount of plowing needed to keep crop fields in production in a given year (20-40 acres) could be accomplished in about a month.

Reflecting on the frontier in 1824, Rev. Joseph Doddridge10 explained the farm design that settlers had in mind as they selected their land:

The division lines between those whose lands adjoined were generally made in an amicable manner, before any survey of them was made, by the parties concerned. In doing this, they were guided by the tops of ridges and water courses, but particularly the former. Hence the greater number of farms in the western parts of Pennsylvania and Virginia bear a striking resemblance to an amphitheatre. The buildings occupy a low situation and the tops of the surrounding hills are the boundaries to which the family mansion belongs.

Our forefathers were fond of farms of this description, because, as they said, they were attended with this convenience “that everything comes to the house downhill.” (Doddridge)

The Doddridge quote is a kind of Rosetta Stone for early farm design in Pennsylvania and Virginia. Doddridge is pointing out why the ridges were used as boundaries, where the house and barn were placed with respect to sloped land, the functional relationships of crops coming downhill from upland fields, and so forth. Doddridge adds a comment about land divisions in Ohio at the end of the passage:

In the hilly parts of the state of Ohio, the land having been laid off in an arbitrary manner, by straight parallel lines, without regard to hill or dale, the farms present a different aspect to those on the east side of the river opposite. There the buildings as frequently occupy the tops of hills as any other situation.

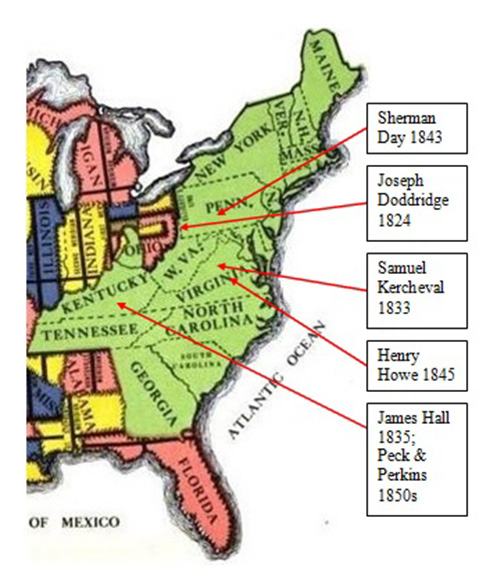

The explanation Doddridge gives apparently resonated across Appalachia. His 1824 book was privately published and only distributed to a few friends. However, it made its way to far flung places in Virginia, Kentucky, and beyond. The book is brief, but it contains extensive information on how people on the frontier traveled, hunted, cooked their food, built houses, celebrated weddings, used alcohol, and similar topics.11 Perhaps in the interest of honoring Doddridge and helping him distribute his narrative throughout the greater Appalachian region, several other authors quoted the entire book, or most of the book, verbatim, as a chapter in regional histories that appeared a quarter century or more after the initial 1824 publication (Figure 5). These later books usually attribute the narrative to Doddridge, but the passage has frequently been misattributed by modern historians who apparently noticed only the main author’s name on the title page of the larger book.12 This suggests that Doddridge’s explanation for farm design, as well as log construction and other topics, not only struck the mid-nineteenth century authors as applicable to other Appalachian areas, but also that the twentieth century authors also see it as an authentic description of those places. It is an accurate explanation for how non-rectilinear boundaries were set throughout Appalachia, and it relates directly to farm design as it developed organically, farm after farm, on hundreds of thousands of sites across several states before the Continental Grid was established for Ohio and beyond.

Figure 5: The map above (from Peters, Ohio Lands…) shows the states where state laws and customs set the rules for land grants (in green), with several grid systems for federal lands west of them (in other colors). Overlain are the dates and names of authors of regional history books that copied the Doddridge narrative, with arrows pointing to the areas where the narrative was considered applicable.

Among the things that Doddridge does not explain is how the organically set boundaries became increasingly important to the mix of farming activities and animals that farmers, largely from Pennsylvania, took with them as they moved west across the state and southwest through Appalachia. Pennsylvania’s agricultural system was geared to producing grain at least until the 1820s. Though focused on grain, the farmers called the system “mixed farming” or “mixed husbandry.” Most settlers showed up on a given tract with a couple of heads of cattle and a couple of sheep, some of each gender. They may have had hogs, geese, chickens, and other animals as well, but the emphasis was on cows and sheep. They kept these animals, partly because the frontier family relied on the milk, wool, meat, and other animal products they provided. (Too often, though, modern commentators have assumed that the animals were kept primarily for these products.) They also used some of the male cattle as oxen to pull plows and carts, at least until horses became common. However, it is clear in the earliest literature13 that farmers understood that they needed animals principally to produce manure in order to keep grain fields productive. Sheep ate stubble and lesser quality materials from last year’s grain, essentially “turning it into manure,” and barn manure (mainly from cows) was mixed with straw and other grain by-products to compost everything left over from reaping, threshing, and winnowing into fertilizer to get the nutrients back onto the fields. They were widely praised in early literature for the way they ate weeds and leftovers from last year’s crops and for being the only animal that produced more value in the form of manure than it cost to keep them (Steele, Randall).

The farm families built their flocks and herds based on what their specific farm needed to stay fertile. As the land was gradually cleared, sheep became increasingly important in those counties where the topography of the typical farm was curled up at the outer edges, because such land was the natural habitat of sheep. The steeply sloped outer fields were not suitable for pasturing cows in rotation, and they could not be easily fertilized with carted barn manure. For this purpose, the sheep needed to be out-of-doors as much as possible, and because of predators, they needed to be watched from a central vantage point. Therefore, land “over the ridge” in the next watershed was of little use to a farmer whose outer fields were kept fertile by pasturing sheep.

Farms with sloped land at the boundaries came to rely heavily on sheep in proportion to the grain they produced. They became increasingly fertile as long as the sheep were kept out in the outer fields.14 These farms initially tended to be further from urban markets and ports; therefore, grain, alcohol (distilled grain),15 and wool were critical as cash goods, especially before the arrival of steam travel and railroads, because they were the longest-lasting farm goods of the era. Farmers were not initially concerned about selling wool, meat from the sheep, or sheep as livestock. Their concern was to keep their grain fields productive.

In those areas closer to the early cities and shipping centers, such as Philadelphia, level land could ultimately support more lucrative farming centered on cows and a variety of crops. These farms could focus on producing perishable but more valuable goods like milk and meat. The Lancaster Plain, for instance, had farms where the ridges were so close to level that they were nearly invisible.16 The outer fields stopped at “dividing ridges,” but they were barely perceptible lines between minor watersheds in land that otherwise looked level. The same farms often relied on wells because the land did not slope enough to create a natural fall line with springs. Initially, before the majority of the land was cleared, Lancaster County had substantial flocks of sheep and many fulling mills.17 However, the farmers gradually moved toward emphasizing cattle in response to landscape characteristics and the availability of markets for perishable goods. An adequate and growing market for dairy and beef existed in Philadelphia, Lancaster, and other nearby cities. Because the outer land is as level is it is, farms with larger herds of dairy cattle could keep the fields in production by composting barn manure and carrying it out to the fields.18

Thus, the irregular boundaries of Pennsylvania farms led to a specific kind of farm layout that came in at least two subtypes, those farms with steeply sloped outer fields growing steeper toward the ridges where sheep were typically regarded as indispensible, and those with nearly level land at the ridges between watersheds where cows and crops beyond grain could be emphasized. There is undoubtedly a range of variations between these two types. The variations are reflected in barn design. When sheep were kept to produce manure for the fringe areas of the farm, there was less need for a centralized barn with a large stable and more need for scattered field barns. Smaller, scattered barns could be used to store hay and bring sheep in when the weather was most inclement. Still, in many cases, a farm with a large flock also often had a large threshing barn because the sheep helped to keep the grain operations productive.

Expansive level fields and level land at the ridges, on the other hand, made a farm more suitable for a large dairy herd (to the extent that the market for dairy products was close enough). These farms had larger centralized barns and more emphasis on the design features of the stable, along with more granary space for animal feed in the upper story of the barn, as well as more emphasis on storing hay and straw, as opposed to functions related to threshing. The barns were designed or modified to have carefully walled barnyard areas for manure often sheltered by straw sheds (straw was used as bedding to soak up urine, which was also considered a valuable form of manure; when dry straw was gradually added into the manure pile, it facilitated the composting process) (Harris and “Agricultural Discussions…”).

The current landscape continues to reflect these subtypes and variations. In certain counties, sloped land is still associated with sheep, even though today the market for wool, mutton, lamb, and sheep as livestock is minimal. The areas where the open fields of neighboring farms meet at level ridges also continue to have one large barn per farm, larger dairy or beef herds, and crop strips to the edges of the tract as clearly seen in current aerial photography (Figure 6). In the oldest areas (such as Chester County) where some longstanding, often stone barns were built before the land was cleared, each barn was initially designed for a few sheep and a few cows, but by the mid-nineteenth century, appendages had been added to create more room for cows as the farm moved away from sheep. The same barns often have watertight barnyard walls added later for composting manure. Above the composting area, or dungyard, the barn often has projecting roofs and sheds built for straw.

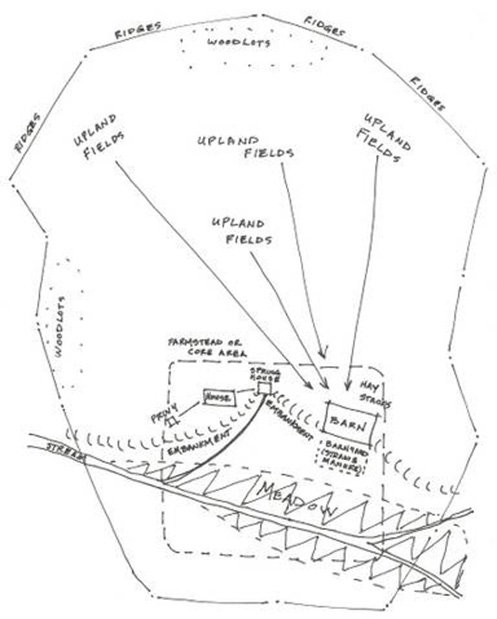

Figure 6: Diagram developed as part of the author’s Peterson Fellowship project to show the parts of the typical Pennsylvania Farm Landscape.

Nineteenth century illustrations, such as atlas drawings, typically show these relationships. Meadows, water features, fall lines, sloped upland fields, woodlots, dungyard walls, stackyards (nearly level, well drained outdoor areas for stacks of hay and straw 19 ), and similar features can be readily identified. Yet there has been little commentary by modern agricultural historians and geographers on how the working parts of the outer landscape affected the layout of the farmstead and the design of the barn (Figure 7). In the atlas drawings for sheep-oriented areas, the outer fields almost always rise above the buildings in the image (Figure 8-11). Scattered small barns are seen in the middle ground in the fields. Farmers are shown plowing steep perimeter fields where the land turns up to the ridges and boundaries. Sheep are prominently displayed in many images. To the nineteenth century agricultural mind, this combination communicated that the sheep were doing their job keeping the outer fields clear of weeds and fertile.20 After machinery came to dominate grain farming, the sloped fields almost completely lost their value. On farms that gave up on raising sheep, the fields became overgrown by invasive plants.21 Current crop patterns in level areas, on the other hand, corroborate this evidence, especially in areas like Lancaster County where outer fields remain productive to the flat-ridged boundaries with a variety of crops beyond just grain.

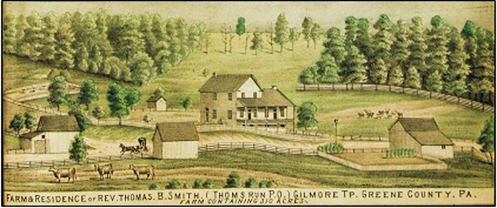

Figure 7: Greene County, an area with steep fields and historically many sheep, often has small barns as shown here. The upland fields are still being cleared on the farm shown here. As with most sheep farms, all the fields are in easy view of the house. (Caldwell, Atlas of Greene County…)

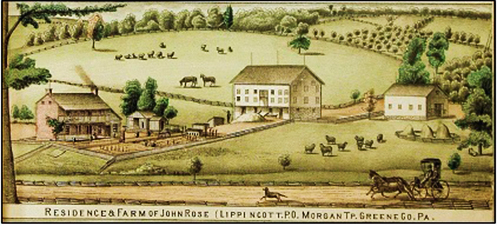

Figure 8: The John Rose Farm in Morgan Township, Greene County, is depicted (below) with sloped fields pasturing sheep in view of the house. The main barn has a pile of manure and/or straw outside the stable wall, probably composting. But the pile is surrounded by a wood fence instead of a stone wall, because there was little concern for conserving every bit of manure run-off in the counties where sheep were plentiful. Note that the upper edges of the fields rise well above the buildings. (Caldwell, Atlas of Greene County…)

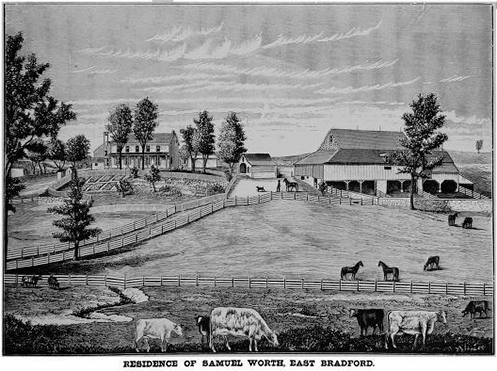

Figure 9: The image above (Futhey and Cope) shows the Samuel Worth Farm, East Bradford Twp., Chester County. The low side of the barn is surrounded by a dungyard wall. A large upper story strawshed has been added to the original stone form partially sheltering the manure pile. The addition extends around two sides of the barn. Many early stone barns in Chester County were altered when farms added cattle and moved away from sheep. The land is sloped, but note that the buildings rise above the landscape horizon.

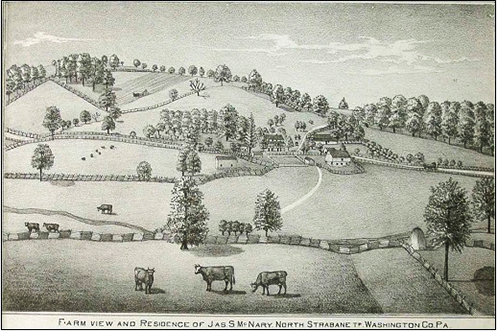

Figure 10: On the Washington County farm below, a steep upland field is being plowed. Cattle are in the more level fields and sheep are in the sloped middle ground field where there are several barns. Note that the upper edges of the fields rise well above the buildings. The artist has under-represented the sheep and acreage (showing only about 6 sheep on what appears to be about 150-200 acres): a directory in the back of the atlas says McNary had 238 acres and a flock of 550 sheep. (Caldwell, Atlas of Washington County…)

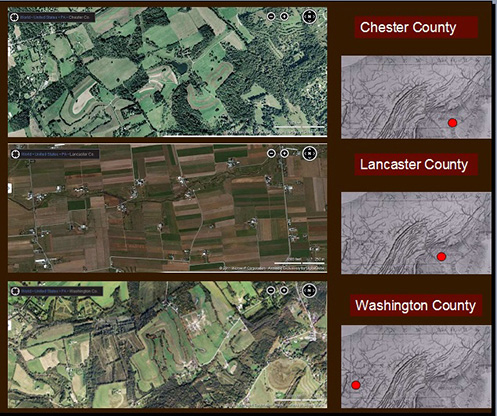

Figure 11: Comparison of landscape, field, and crop patterns in aerial views of three counties as they appear today. Chester and Washington Counties look similar. The difference is that Washington County has more concave patterns of bowl-shaped farms, and Chester County has more convex hillocks interrupting the landscape. In both cases, the crops reflect contoured land and hills and/or bowl-shaped components of the larger farms. In Lancaster County (specifically in the Lancaster Plain), most of the houses, barns, and farmsteads are clustered close to the streams and other water sources; the edges of the farms are not straight lines, but the crops fill the land from stream to stream crossing over nearly level interfluvial ridges. (Aerial maps from Bing Maps web site, finder map based on contour map from Relief Map of Northern Appalachians, U.S. Geological Survey, 1908)

The angled boundaries that mark the land in southern Pennsylvania and throughout much of Appalachia are evidence of eighteenth century assumptions in farm design that became realities as land was cleared and as farms evolved and developed in the nineteenth century. They represent a geographic characteristic whose distribution is traceable and reflects the internal organization of farms as well as design of the buildings and other resources. The functional aspects of farming that they embody varied in subtle ways from one area to another, depending upon the importance of activities like sheep raising, dairy production, and crop specialties. However the geographic domain of non-orthogonal boundaries stops abruptly near the Ohio state line, where it also ended historically as the federal government imposed the Cartesian grid system now sometimes called the American Continental Grid. The controversy over what New Englanders labeled “indiscriminate location” brought a sudden end to an important tradition of organic farm design in Pennsylvania and Virginia (including what is now West Virginia), even leading Pennsylvania to reintroduce rectilinear geometry in areas claimed after 1787. The system can be further studied as a geographic phenomenon that correlates closely to the distribution of the Pennsylvania barn and its variations in style and design.

Works Cited

“Agricultural Discussions at the State Fair — Management of Manures, The Cultivator, Albany: Luther Tucker and Son, October 1861, Vol. 9, No. 10, page 317 (accessed at Google Books).

Beach, Richard, Two Hundred Years of Sheep Raising in the Upper Ohio Area, Washington, PA: Washington County Commissioners, 1981.

Beach, John Richard, The Sheep Industry in the Upper-Ohio Valley, 1770-1973: A Geographical Analysis. Doctoral Dissertation for the University of Pittsburgh, 1973.

Billings, G.A., “Dairy Farming in Southeastern Pennsylvania — Bulletin 159,” Selected Bulletins, Volume 25, pages 10-15 (accessed at Google Books).

Bioren, John, Laws of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia: John Bioren, 1810, page 103 and pages 202-204, 215, and 217 (400-acre rule), and pages 162 and 172 (300-acre rule). (accessed at Google Books).

Brodie, D.A., Handling Barnyard Manure in Eastern Pennsylvania, Farmers’ Bulletin 978, Washington, D.C.: Office of the Secretary of the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, 1918, Pages 4-9 (specifically on Chester County examples) (accessed at Google Books).

Caldwell, J.A., Atlas of Greene County Pennsylvania. Condit, Ohio: J.A. Caldwell, 1876.

Caldwell, J.A., Atlas of Washington County, Pennsylvania. Condit, Ohio: J.A. Caldwell, 1876.

Clowes, William, British Husbandry, London: William Clowes, 1834, Vol. I, pages 496-502 (accessed at Google Books).

Doddridge, Joseph (Narcissa Doddridge, and William Thomas Lindsey,) Notes on the Settlement and Indian Wars of the Western Parts of Virginia and Pennsylvania, Pittsburgh: 1912 edition of 1824 text.

Fischer, David Hackett, Albion’s Seed, Oxford University Press, 1991, page 760.

Fletcher, Stevenson Whitcomb, Pennsylvania Agriculture and Country Life, Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Vol. 1, 1955, page 25

Futhey, John Smith and Gilbert Cope, History of Chester County, Pennsylvania, with Genealogical and Biographical Sketches, Philadelphia: Louis H. Everts, 1881, page 339.

Gordon, Thomas Francis, A Gazetteer of the State of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia: T. Belknap, 1832.

Hall, James, The Romance of Western History: or, Sketches of history, Life, and Manners in the West, Cincinnati: Applegate and Company, 1857, page 78 (accessed at Google Books).

Harper, R. Eugene, The Transformation of Western Pennsylvania, 1770-1800, Pittsburgh, Pa.: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1991.

Harris, Joseph, Talks on Manures: A Series of Familiar and Practical Talks between the Author and the Deacon, the Doctor, and Other Neighbors, on the Whole Subject of Manures and Fertilizers, New York: Orange, Judd Company, 1893, page 118 (accessed at Google Books).

Hoefling, Larry, Chasing the Frontier: Scots-Irish in Early America, published online by iUniverse, Jun 30, 2005.

Keith, Gov. William, “Sir William Keith to Lords of Trade, Nov. 27 and Nov. 28, 1728,” New Jersey, Archives, V, 203, 204, 205, 206, as quoted in: History of manufactures in the United States ... by Victor Selden Clark, Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1916, page 202, (accessed at Google Books).

Klein, Philip S. and Ari Arthur Hoogenboom, History of Pennsylvania, University Park, PA: Penn State Press, Nov 1, 2010, Page 183. (accessed at Google Books).

La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt (duc de), François-Alexandre-Frédéric, Travels through the United States of North America: The Country of the Iroquois, and Upper Canada, in the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797, London: R. Phillips, 1800, Vol. 4, pages 77-78.

Leyburn, James G., The Scotch-Irish: A Social History, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989 (reprint), page 205.

Maps of Pennsylvania Land Claims (Warrantee / Patent Maps) by township, available at the web site of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission at: http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/bah/dam/rg/di/r17-522WarranteeTwpMaps/r17-522WaranteeTwpMapMainInterface.htm

Mombert, Jacob Isidor, An Authentic History of Lancaster County, J.E. Barr & Co., 1869, pages 413-418 (accessed at Google Books).

Munger, Donna B., Pennsylvania Land Records: A History and Guide for Research, Wilmington,

DE: Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1993, pages 65-66 (accessed at Google Books).

Pattison, William David, Beginnings of the American Rectangular Land Survey System, 1784-1800, (Research Paper NO. 50) Department of Geography, Chicago, IL, 1964 (accessed at Google Books).

Peters, William Edwards, Ohio Lands and their Subdivision, Athens, Ohio: W.E. Peters, 1918 (accessed at Google Book)

Randall, Henry S., “Sheep Husbandry and Wool Growing in the United Stares,” Report of the Commissioner of Patents for the Year 1850, Part II, Agriculture, Washington, D.C.: Office of Printers to House of Representatives,1851, pages 129-144.

Sampson, H.O., Effective Farming, New York: MacMillan, 1918, pages 67-78, especially page 76 (accessed at Google Books).

Steele, John D., “On Sheep,” Memoirs of the Pennsylvania Agricultural Society, Philadelphia: J.S. Skinner, 1824, pages 1-4, (accessed at Google Books).

Schneider, David B., Foundations in a Fertile Soil: Farming and Farm Buildings in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, Lancaster, PA: Historic Preservation Trust of Lancaster County, 1994.

Wenger, Samuel E., “Brief History of 1710 Pequea Settlement,” 1710 Pequea Settlement Tour Resource Information Booklet, Mennonite Historical Society, No Date, pages 1-6, accessed online at: http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb. ancestry.com/~boehm/data/1710_Pequea_Settlement.pdf.

Endnotes

1 This paper, as delivered at the 2012 PAS/APAL Conference, summarizes much of the research and analysis of a project entitled “The Pennsylvania Farm Landscape as a Historic Resource” the author prepared as the Athenaeum of Philadelphia’s 2011 Charles E. Peterson Fellow. Much of the analysis was a collaborative effort with Pioneer America Society member Laura Walker, an anthropologist and working farmer. It is also based on a paper presented at the 2010 Pioneer America Conference in Castleton, VT. It is also based on a paper Laura Walker presented at the 2001 PAS/APAL conference on the field barns used for sheep on farms in southwestern Pennsylvania.

2 The three original counties of Pennsylvania were Philadelphia County, with Bucks County north of it and Chester County southwest of it. Penn and his first surveyor, Thomas Holme, began with a street grid at Philadelphia, laid out generally rectangular farms on a grid-like diagonal in Philadelphia County, and then extended the patterns into Bucks and Chester Counties one township or cluster of farms sold at a time.

3 The Pequea Settlement in Lancaster County was one of Penn’s last efforts at selling land before he died (Wenger, Mombert). Like most of the land Penn sold in his lifetime, the tracts were based on rectangles, but tilted on an angle of 20-45 degrees with respect to north; some were among the largest tracts he sold.

4 Many of the towns in the Western Reserve, or northeastern quadrant of Ohio, are named for towns in Connecticut from which a group of settlers came. Another aspect of this difference between southern Pennsylvania and areas north and northwest of it is that the northern settlements involved large purchases by land speculators who then helped relocate a community; further south, land speculation was less trusted.

5 This pattern extended into North Carolina, Kentucky, and other adjoining areas with the topography of hills, hollows, eroded plateaus, and other features that typified the Appalachian region.

6 Chester County historians describe the importance of meadow in selecting land (Futhey and Cope). While this is one of the oldest parts of Pennsylvania, the explanation fits later farm selection further west.

7 The acre was originally an oblong unit, from a time when European crop fields were sometimes bounded by stone walls. The oblong shape was a way to limit the number of furrows because of the difficulty of turning the team and plow at the end of the furrow. The length of an acre was a “furlong,” a word that came from shortening the phrase “a furrow long.”

8 This was initially the author’s observation in studying land patent maps, but the nineteenth century sources confirm a sense of a moral limit to land claims (Hall), which corresponds closely to 365 days/year.

9 This topic is the source of some historical commentary about the southwestern corner of Pennsylvania, where Virginians claimed an area containing five modern day counties in the 1770s. A considerable number of Pennsylvania natives wanted the area to be included in Virginia to allow larger land grants.

10 Doddridge was a frontier minister who served Episcopal churches in what is now the Northern Panhandle of West Virginia, at the Pennsylvania state line. He was born in 1769 in Bedford (just west of center in the southern half of the state), which, beginning in 1771, became Pennsylvania’s county seat for all the areas from there west. The area beyond Bedford was rapidly expanding as a result of a new land office opening in the year of Doddridge’s birth. When the family relocated in 1773, they moved 125 miles west to what is now Independence Township, Washington County, close to the state’s western line.

11 Noted geographer, the late Terry Jordan, an active participant in PAS/APAL, told the author at the 2000 Pioneer America meeting that he found the Doddridge narrative to be among the most useful and reliable known texts by an early nineteenth century historian on frontier farm culture and log construction.

12 E.g., David Hackett Fischer attributed the Doddridge narrative to Samuel Kercheval (Fischer, page 760).

13 As early as 1728, Pennsylvania’s governor, Sir William Keith, wrote apologetically to the British Crown defending the fact that his colony was producing wool contrary to Britain’s Woolens Act of 1699. He explained that the wool was simply the by-product of keeping grain fields in production. In Gov. Keith’s words: “Their principal product is stock and grain, and consequently their estates depend wholly upon good farming and this can not be earned on without a certain proportion of sheep (which in a good pasture there, lamb twice a year and every ewe generally brings two and often three lambs at a time) so that the wool would be lost, if they did not employ their servants at odd times, and chiefly in the winter season to work it up for the use of their own families.” Other sources indicate that the farmers themselves knew they needed sheep to raise grain on sloped land near ridges.

14 Washington County, where there were over 1 million sheep by the 1880s, was topographically prone to lose fertility on cleared land from erosion, but kept returning to remarkable fertility as a result of the sheep.

15 Farmers regularly operated distilleries across Pennsylvania in the 1700s to make grain surpluses into something of equal value that was less perishable and easier to transport. The difficulty of preserving and transporting grain surpluses, vis-à-vis the way taxes (presumed to be on a luxury item) threatened that system, was the central concern of farmers in the Western (or Whiskey) Insurrection of 1794.

16 An eighteenth century passage to this effect is frequently quoted about early agriculture in Lancaster County, but generally without explanation. The passage is, in part, “…he entertains the same prejudices as the rest of the farmers in favour of flat ridges, and against sheep…” (La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, Schneider). The point is about certain farmers preferring, and migrating to, land with nearly level outer fields as a step toward using carted barn manure rather than sheep to keep them fertile. In time, this prejudice led to much more thorough crop coverage on the Lancaster Plain than what typifies Pennsylvania.

17 Lancaster farmers developed an interest in a specific breed known as Tunis sheep before 1800. Fulling mills were facilities, similar in some ways to grist mills (sometimes water-powered) where woolens woven or knit at home from homespun thread were cleaned and beaten to remove lanolin and lock the threads together. Lancaster County had over 30 fulling mills by the 1830s (Gordon), suggesting it was then one of the state’s more productive counties for homespun woolens. Sheep quickly fell out of favor after this.

18 Farmers frequently expressed concern in Lancaster (Schneider) and Chester Counties over whether one’s neighbors were adequately conserving all the nutrients they could from their barn manure, a major theme in nineteenth century written commentary by famers in the area, a theme scarcely mentioned on sheep farms.

19 For additional information on how stackyards, or “rickyards” were designed, see Clowes.

20 The illustrations can be as symbolic as much as they are representative. However, the idea that they may be symbolic does not necessarily mean they are exaggerated to show more than what was actually there. Caldwell’s Centennial Atlas of Washington County has a farm-by-farm directory at the back listing owners, acreage, and so forth. The column for sheep precedes the owner’s name implying it is the most important information. The numbers given are generally much higher than what the illustrators showed in the images.

21 Richard Beach paid special attention to the effect of removing sheep from the landscape in Two Hundred Years of Sheep Raising in the Upper Ohio Area, as well as in his earlier doctorial dissertation, The Sheep Industry in the Upper-Ohio Valley, 1770-1973: A Geographical Analysis. Beach’s work was groundbreaking specifically in its concern for identifying landscape features on fine-wooled sheep-oriented farms in southwestern Pennsylvania. The research for the current paper began by drawing heavily on it.

Author Biography

Terry A. Necciai, RA, has worked as a preservation architect and architectural historian since 1981. He has written many National Register nominations, including 16 for southwestern Pennsylvania farms. The Athenaeum of Philadelphia awarded him the 2011 Charles E. Peterson Fellowship to study “The Pennsylvania Farm Landscape as a Cultural Resource.”