Catskill Mountain House: Social-Spatial Delineations in an Iconic American Landscape

Courtney Allen, Botanical Education Manager,

The Huntington, San Marino, CA

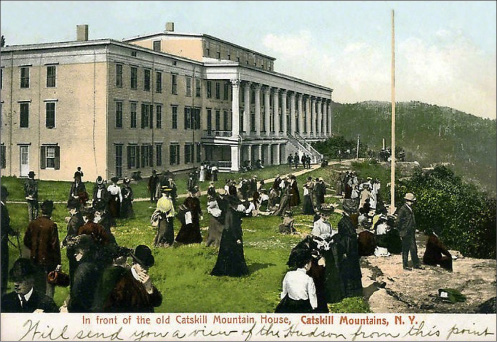

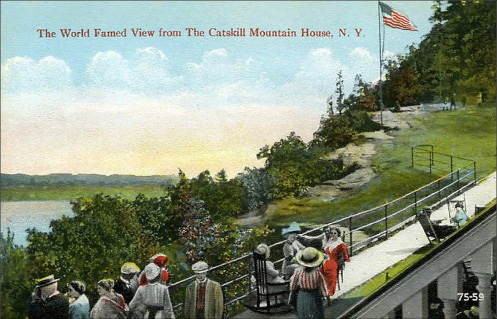

Catskill Mountain House was the first mountain resort in the US, operating from 1824 to 1942. Known as the nation’s playground, the entity shaped how Americans constructed concepts of landscape and nationalism. Catskill Mountain House has been amply discussed by scholars as the birth of nature tourism and environmental history, the epitome and pioneering effort of upper class luxury, and the cultivation of an American aesthetic taste through the talents of the Hudson River School. Yet, little literature exists examining Catskill Mountain House’s exploration of social distinctions during the nineteenth century – how the economic diversification of the clientele may have altered social behaviors, and how that may have been evident in the physical landscape and in interpretations of the landscape. In a region and time of class stratification and increasing transportation technologies, how might Catskill Mountain House have served as an experimental model for a mixed, socialized landscape of leisure? What divisions existed in America’s playground? Ultimately, what does it mean to have a collective experience in a situation where people are “not like you” (Figure 1)?

Figure 1. Postcard of the Catskill Mountain House on a busy day. Catskill Archive.

In this paper, I intend to demonstrate that Catskill Mountain House served as an experimental model for a broadening definition of leisure over the course of the nineteenth century: addressing who was considered eligible and by whom, the expectations and technologies that encouraged these assumptions, and how these distinctions are suggested within evidence of the landscape. I will examine this thesis through primary sources such as the hotel’s floor plans, art and memorabilia, as well as secondary literature pertaining to nineteenth century American ideas of class, culture, tourism, and leisure.

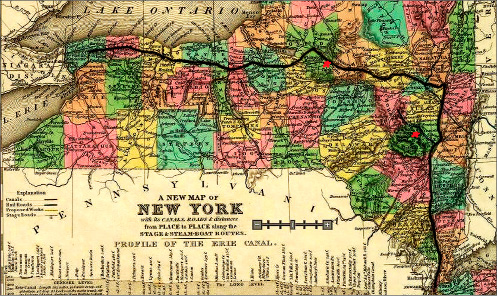

Figure 2. Tanner, Henry S. A New Map of New York with its Canals, Roads & distances from Place to Place along the Stage & Steam-Boat Routes. Philadelphia: H. S. Tanner. 1836. David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

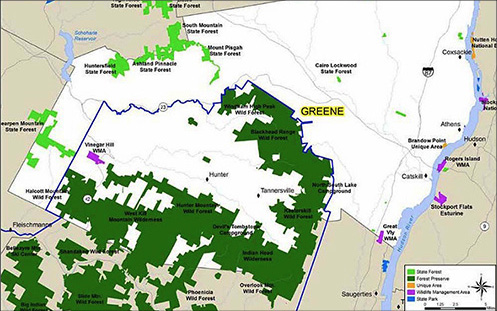

Figure 3. New York State Dept. of Environmental Conservation. Map of State Land in Greene County.

Part I: Region

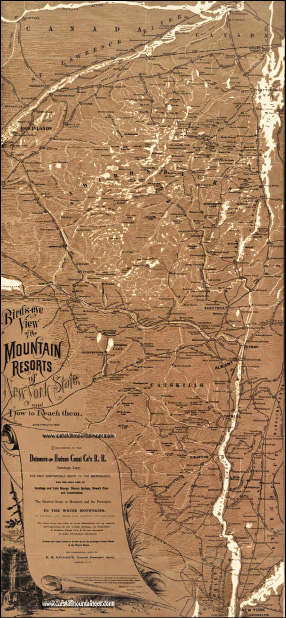

Much literature examining the popularity of Catskill Mountain House as an early American tourist spectacle approaches from a deterministic viewpoint, claiming that the geographic location between the Erie Canal and New York City deemed these mountains as the inevitable place for the first resort. The steamboat travel route began in New York City, 100 miles south of the resort area, ran north along the Hudson River and then another 350 miles west to Niagara Falls (Figure 2).1 But the Catskill Mountains were not strictly a place to gawk at natural wonders; “Catskills” grew to form an experimental world of travel expectations, of distinct artistic and intellectual culture, and ultimately of social interactions.

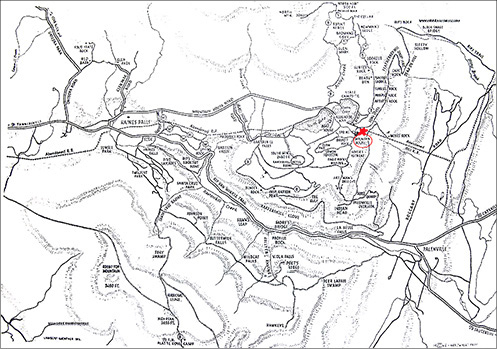

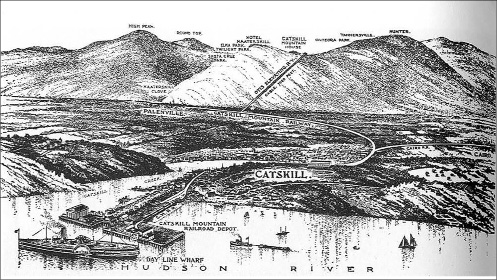

“Catskills” originally referred to the area just opposite of the town of Catskill, where the resort was established, an area of about 20 square miles.2 Yet the desire to create a scenic park of the region, based on the resorts, constantly pushed the boundaries throughout the nineteenth century; today, Catskill State Park encompasses 900 square miles. The Catskill Mountain House was located in the saddle between two mountains and two lakes. The south side was the popular side during the entire time the resort was running, as opposed to today’s north side popularity (Figures 3-4).3 From the property, visitors could see for about 70 miles, including the Berkshires and the Connecticut River Valley.

Figure 4. Guenther, Lambert. 1949 Arrowhead Map. 1949.

The resort was obviously not easily accessible. When Catskill Mountain House was first established in 1824, visitors would ride steamboats up the Hudson, disembark at Catskill (or at Kingston, after the Civil War), and take a stage coach up a rough mountain road for 4-6 hours at a high cost (Figure 5).4 Transportation was limited, expensive, time-consuming, and exhausting; however, the separation offered a retreat experience. At the top awaited a white, neo-classical hotel on a cliff ledge – small in 1824, with 10 rooms, which grew to over 300 rooms by the end of the nineteenth century. The resort promised accommodations and luxuries comparable to any found in New York City – for elite on retreat from the city.

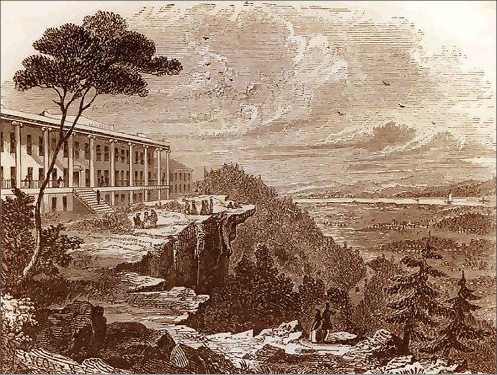

Figure 5. “The Catskill Mountain House, in the midst of grand and peculiar scenery, on the verge of a rock two thousand and five hundred feet above the Hudson – seen with its various fleets at a distance from its long colonnade – is thronged even more than West Point.” From “A Glance at the Watering Places.” The International Monthly Magazine of Literature, Science and Art, August 1851.

The Catskills were not simply geographically linked to the city; the resort culture that developed was dependent upon New York City tastes and expectations. The reflection of urban culture in the woods also meant that as socioeconomic trends changed in the country, and transportation technologies were developed to more fluidly bring culture to nature, the socialization structures of the resort coalesced.

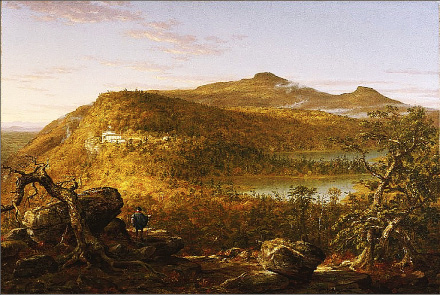

What did people come to see at Catskill Mountain House? Who were the audiences and what were they creating and experiencing? Why was this space created, and why at this place and time? With the Erie Canal near completion in 1824, a small association of investors created the Catskill Mountain House, and Thomas Cole began his famous landscape paintings there the following year. Cole provided the foundation for a school of romantic artists, which, in tandem with literary giants such as Irving, Cooper, and Bryant, glorified the beauty of the region, imbuing it with spiritual significance. They depicted “a true wilderness”, the defining and unique feature of the new nation (Figure 6).5 The natural resources, and the American desire to cultivate them, were the basis of collective goal and identity, and pervaded intellectual media through the well-to-do circles in New York City. Societal expectations in turn shaped the artists’ renderings – creative interpretation with a realistic appearance.

Figure 6. Thomas Cole. A View of Two Lakes and the Mountain House, Catskill Mountains, Morning. 1844. Brooklyn Museum.

Visitors sought this domesticated wilderness, a picturesque and static viewscape.6 The irony is that the ideal views that visitors sought were unknowingly often the damaged remains of tanneries and bluestone quarrying. These clearings and fires were sometimes what made these views possible.7 In fact, compared to other early tourist spectacles in the United States, the Catskills and the Hudson River Valley below were refined landscapes, demonstrating agricultural progress and a pastoral ideal.8 This representation and panorama of American evolution was responsible for the attraction to the region.

Part II: Hotel Constructions of Social Space

In considering the plausible class interactions and dynamics established at Catskill Mountain House, we must examine the physical landscape – not only the natural resources and their cultural representations, but the resort complex itself. What is Catskill Mountain House’s place in the larger national hotel movement? What can we deduce from the structure’s layout and circulation? And centrally, what do these distinguishing features suggest about a concept of “public domesticity”?

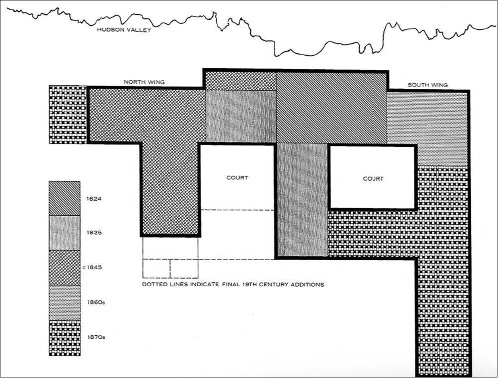

Figure 7. “Sketch Plan. Growth of the Catskill Mountain House. Prepared by Roland Van Zandt from rough plans drawn by Claude Moseman in the 1940s; Drawn by Karen Waldauer.” In Van Zandt’s The Catskill Mountain House, p. 262.

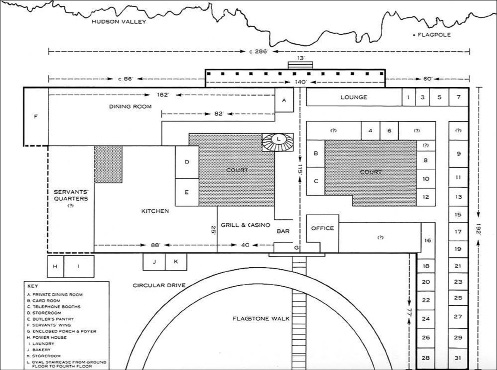

Figure 8. “Sketch Plan. Ground Floor of the Catskill Mountain House. Prepared by Roland Van Zandt from rough plans drawn by Claude Moseman in the 1940s; Drawn by Karen Waldauer.” In Van Zandt’s The Catskill Mountain House, p264.

Hotels in the United States fulfilled a unique role, different from nations without a colonial past and without massive amounts of unexplored territory. These institutions became communities in a constant state of transition and transformation, a temporary home for new guests and new ideas, a microcosm of greater American trends. They raised awareness and provoked questions of people’s relationships to place and to each other, acting as social centers for a migratory people: “Americans lived in a new realm of un-certain boundaries, in an affable, communal world which, strictly speaking, was neither public nor private…The classic locale of this new American vagueness, for this dissolving of old distinctions, was the hotel.”9 The hotel restructured and redefined boundaries – of privacy, of class, of gender, and near the end of the nineteenth century, of race. In order to approach these social structures, we must examine the spatial structures that hosted and encouraged them.

The neoclassical choice of architecture for Catskill Mountain House may seem anachronistic or jarring to the natural scenery. However, this fails to take into account the hotel’s growth. First, when the resort was originally constructed in 1824, it was a small rectangular Federal building; it was not until 1845, with the third of four additions, that the iconic neoclassical façade was constructed (Figures 7-8). Second, luxury hotels in cities were frequently monumental, built in the neoclassical style to be recognizable as public spaces.10 The architecture of Jacksonian democracy was the main driving force in this choice for legibility.11

While extant floor plans of Catskill Mountain House are minimal, we can note some indications of an inflexible floor plan. Much of the interior deferred to small, highly delineated spaces. From the time Catskill Mountain House was initially constructed, through its enormous growth over the nineteenth century, the resort remained in dormitory style, with comparatively small private rooms and shared bathrooms. There were two courtyards that became enclosed, and suggest exclusivity for hotel guests in later years when tourism increased. A large dining room is also present; however, a second one was built later on for people who could not afford to stay in the hotel. We can also see that a large part of the first floor interior is dedicated to services of the privileged – servants’ quarters, kitchen, and casino. According to the floor plans, we must conclude that the resort throughout the nineteenth century was constructed specifically to maintain guest privacy inside, and to encourage socialization outdoors – the featured attraction of the mountain resort.

There was, however, an in-between space, a borderland: the verandah. The piazza, as it was called, was added to the hotel in 1844 and served as the primary space for socialization. It was a feature partially open to the elements, encouraging promenade and other physical activity; it framed the wilderness, creating a separation yet also a sense of belonging (Figure 9).12 The piazza also framed the entrance into the resort and served as an impressive beacon. It was on the piazza that guests and visitors gathered to experience the natural and cultural collectively.

Figure 9. Piazza of the [Catskill] Mountain House. 1897. Catskill Archive.

While the neoclassical porch may be perceived as an English cultural import from the picturesque movement, there are stronger ties and significance to the Catskills region. The Hudson Valley Dutch were leaders in establishing the domestic porch in America.13 Respect for Dutch architecture increased drastically in the mid-nineteenth century, due to the influence of the picturesque and a desire to identify American remains.14 The piazza was a complex and paradoxical symbol of domesticity.15 It welcomed guests and announced the site as a public institution, but simultaneously modeled the porches of private homes, particularly those of new middle class America designed by AJ Downing. Therefore the piazza, by making public use of a private architectural feature, created a space associated with recognition of wealth and status, though simultaneously claiming to represent democratic ideals.16

Part III: Technology and Diversification

What, then, took Catskill Mountain House from an exclusive resort to an American pilgrimage site, where people from disparate classes could enjoy the spectacle of Cole’s romanticism as imposed on the Catskills?17 How did people outside of the New York society circles learn of it? And once Catskill Mountain House became accessible to people of different spheres, how did these groups co-exist, or possibly integrate?

Due to the mid-nineteenth century boom in mass printing, images of geographies became more and more common. The development of tourist guidebooks interpreted America’s resources for a larger public,18 and American spectacles were no longer limited to the upper class (Figure 10).19 Diversification at Catskill Mountain House was a result of the emergence of a middle class in urban settings. Beginning in the Jacksonian era and strengthening in post-Civil War America, a new middle class arose that did not adhere to the standard Marxist construction of profiteers and laborers. It created a new culture of working professionals – “white collars” – who were financially dependent upon their non-manual trade, but could afford leisure activity.20 During the last quarter of the nineteenth century, members of New York City’s emerging middle class would often visit Catskill Mountain House just for the day.

Figure 10. Postcard of The World Famed View from The Catskill Mountain House, N.Y. Catskill Archive.

The idea of day visitation – of tasting and participating in the resort culture without paying for the hotel itself for extended periods of time – was made possible by the railroad. The first railroad was constructed by the Ulster and Delaware Railroad Company in 1866, and ran through Kingston. Charles Beach, the proprietor of Catskill Mountain House for most of the nineteenth century, was consistently astute regarding transportation technology and its potential benefits for his establishment; thus, by 1882 there was a rail line that went to the town of Catskill. As though this was not direct or dramatic enough, Beach also installed an Otis Elevating Railroad (essentially a funicular) in 1892, connecting the resort to the town below. While the increased accessibility was protested by surrounding hill towns and Romantics, the middle class took advantage of this rapid and reasonably priced transit (Figures 11-12).21

Figure 11. “Birds-eye View of the Mountain Resorts of New York State and how to Reach them.” Delaware & Hudson Canal Co.’s R.R. www.catskillmountaineer.com.

Figure 12. Transportation system. Van Loan’s Catskill Mountain Guide (New York, 1909), p.6.

The possibility of commute also changed the gender implications and family structure at Catskill Mountain House, allowing male professionals to come for the weekend and return to work in the city during the week. As such, some middle and upper class families arranged for the women and children to stay in the Catskills for weeks at a time while the male household heads were working. As a result, the resort area in the late nineteenth century became more the woman’s domain, one where gender roles were less stringent.22 Not only was there a more flexible consideration of what constituted appropriate behavior, but it brought questions and awareness of the definitions of “ladyhood” into hotel public spaces, reshaping the hospitality industry.23

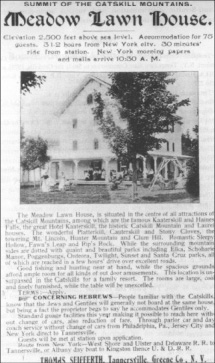

But where did the middle class visitors stay during their vacations in the Catskills, since the prices at the resort were so outlandish? Those who could not afford to stay at the resort predominantly took up temporary residence in boarding houses. Surrounding farm communities, which had predated the resort’s establishment in the 1820s and wisely looked to profit from it, frequently converted their farmhouses into boarding houses. Some were actual inns, capitalizing on the local mythology, such as the Rip Van Winkle Inn; others were simply a few rooms for single people or families who were willing to live in close quarters. For these visitors, a trip to the Catskills was not necessarily luxurious; but it perpetuated a romantic view of rural culture, still gave the opportunity for outdoor wonders, and allowed for day access to Catskill Mountain House.24

For wealthy patrons who found class integration intolerable, there was opportunity for segregation at newly developed resorts, which had cottages and gated communities. The discrimination that had been excused by the upper class under the guise of luxury became more and more blatant; the more diverse the vacationland grew, the more self-conscious the segregation became.25 Yet, during the day, people of various economic and living situations would all spend time at Catskill Mountain House (Figure 13). On the piazza and among the outdoor organized sports on the lawn, middle and upper classes forged methods to share space and interact. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, Catskill Mountain House received 70,000 daytime visitors annually.26

Figure 13. Two Maids from the Twilight Inn. 1910. Catskill Archive.

Figure 14. Hotel advertisement distributed by Ulster and Delaware Railroad. The Catskill Mountains, Ulster and Delaware Railroad (Rondout, NY, 1900), p.140.

While the daytime visitation at Catskill Mountain House grew to encompass a diversity of classes, it remained exclusive in race and ethnicity. The discrimination resulted in the formation of Jewish establishments (called the Borsch Belt) in the early twentieth century, and African-American establishments in the mid-twentieth century (Figure 14-15).27 While the economic depression and frugal mentality of the World Wars and Great Depression was the ultimate reason for the closing of Catskill Mountain House in 1942, the discrimination was likely a contributing factor.

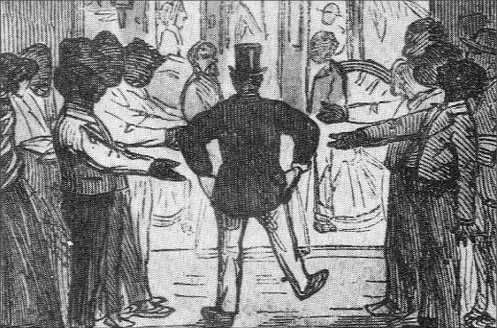

Figure 15. “Departing,” Mountain House; Thomas Nast, 1866. Detail of Sketches Among the Catskill Mountains. [vz fig 63 p287]

Decline

After the closing, the hotel was hit by a hurricane in 1950; the owner attempted a restoration of the structure in 1952, but the cost and labor proved overwhelming for an individual. The site fell into major disrepair and was purchased by the New York State Conservation Department in 1962 (Figure 16). Rather than invest the restoration efforts in the once-famed structure, the state burned it at 6am on Jan 25, 1963, claiming that the structure was incompatible with state article 14 that the Catskills should be “forever keep as wild forest lands” – a decision reflective of the time period’s own hierarchy of preservation values. A landmark for over a century, the Catskill Mountain House helped define Americans’ understanding of environment – naturally, culturally, socially, and in many other ways. As one of the early spectacles, the resort served as a model for collective formation of place, and of learning how to share space with people of different economic backgrounds, who were eager to participate in that process of group identity and site attachment.

Figure 16. Catskill Mountain House, 1953. Catskill Archive.

Endnotes

1 John F. Sears, Sacred Places: American Tourist Destinations in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 3-11; David Schuyler, “The Sanctified Landscape: The Hudson River Valley, 1820 to 1850,” in Landscape in America, edited by George F. Thompson (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1995).

2 David Stradling, Making Mountains: New York City and the Catskills (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2007), 84, 91.

3 Roland Van Zandt, The Catskill Mountain House (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1966), 112-121.

4 Ibid 71-100.

5 Schuyler 97; James Fenimore Cooper, The Pioneers (Charles Wiley, 1823); William Cullen Bryant, “Catterskill Falls,” (1836).

6 Stradling 23-25.

7 Ibid 28-45.

8 Sears 49.

9 Kenneth S. Lynn, “The Americans: The National Experience by Daniel J. Boorstin,” The Kenyon Review Vol.28 No.1 (Jan. 1966): 121.

10 Carolyn Brucken, “In the Public Eye: Women and the American Luxury Hotel,” Winterthur Portfolio Vol.31 No.4 (Winter 1996): 204-205.

11 W. Barksdale Maynard, “’Best, Lowliest Style!’ The Early-Nineteenth-Century Rediscovery of American Colonial Architecture,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians Vol.59 No.3 (Sept. 2000).

12 Flad 362.

13 Joseph Manca, “On the Origins of the American Porch: Architectural Persistence in Hudson Valley Dutch Settlements,” Winterthur Portfolio Vol.40 No.2/3 (Summer/Autumn 2005): 93.

14 Maynard “The Early-Nineteenth-Century Rediscovery of American Colonial Architecture” 338-339.

15Flad.

16 Betsy Blackmar and Elizabeth Cromley, “On the Verandah: Resorts of the Catskills,” in Victorian Resorts and Hotels, edited by Richard Guy Wilson (Philadelphia: The Victorian Society of America, 1982), 53.

17 Ibid 224.

18 Richard Gassan, “The First American Tourist Guidebooks: Authorship and the Print Culture of the 1820s,” Book History Vol.8 (2005); Stradling 92-94.

19 David Buisseret, “Nineteenth-Century Landscape Views,” in From Sea Charts to Satellite Images: Interpreting North American History Through Maps, edited by David Buisseret (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), 112.

20 Stuart M. Blumin, The Emergence of the Middle Class: Social Experience in the American City, 1760-1900 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 1-16.

21 Van Zandt 225-241.

22 Stradling 96.

23 Brucken 203-204.

24 “The Farmhouse as Boarding House: Sharing Values and Sharing Space in the Catskills,” Voices: the journal of New York folklore Vol.26 (2000); Van Zandt 257.

25 “Origins of Tourism in the Catskill Mountains,” Journal of Cultural Geography Vol.11 No.1 (1990); Stradling 102-108.

26 Van Zandt 289.

27 Maria O’Donovan, “A Trip to the Mountains: Travel and Social Relations in the Catskill Mountains of New York,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology Vol.15 (2011); Laura Miller, “’I Built it for You, Now Enjoy it with Me’: The History of African American Resorts in the Catskills” (lecture for The Trustees of Reservations, Sheffield, MA, March 28, 2012).

Contributor Biography

Courtney Allen is a museum professional specializing in site management and landscape interpretation. She has worked at several National Historic Landmarks and is currently Botanical Education Manager for The Huntington in San Marino, CA. Courtney holds an MS in Historic Preservation from University of Pennsylvania and a BA in Landscape Studies from Smith College.

Return to top