Sterling Reputation? Representation and Commemoration in the 1893 World’s Fair Souvenir Spoons

Thomas L. Bell, University of Tennessee

Margaret M. Gripshover, Western Kentucky University

Abstract: The purpose of this paper is to unpack the cultural meaning of souvenir spoons produced to commemorate the 1893 Columbian Exposition. We argue that these spoons represent a form of commemoration and memory that can also be used as forensic evidence of lifestyles at the turn of the 20th century.

A Brief History of the Souvenir Spoon

The spoon in general and the souvenir spoon in particular was not always a banal and utilitarian object of material culture that it has sometimes become today. Rather, during the Middle Ages and the time of artisanal guilds, silversmiths produced spoons that were highly sought after and collectible, especially coronation/anointing spoons used by royalty (Kahn 2013). The apostle spoons of the Elizabethan period were one of the most highly prized collectibles of the age and because of the cultural capital they engendered, allusion to their worth even made it into Shakespeare’s plays (Stutzberger 1971). It may have been during this period that the phrase “he/she was born with the silver spoon in his/her mouth” came into fashion. The collection of expensive souvenir spoons was a de rigueur experience for the cultural elite, especially for the coming-of-age young graduates of Oxford and Cambridge who went on their post-college Grand Tour of Europe during the Gilded Age, particularly in the period starting with the first London World’s Fair of 1851.

With the coming of the Industrial Revolution and mass production techniques, the silver souvenir spoon became affordable for the masses as the whole production system shifted from what Bourdieu (1993) labels restricted production for a knowing intellectual and worldly elite to the mass production of a item of popular culture that is embraced by the bourgeoisie. Thus the silver souvenir spoon takes on an increasingly middle-brow status in his theory of cultural distinction and acquired tastes (Bourdieu 1984).

The Distinction Between a Memento and a Souvenir

The OED defines souvenir as “a thing that is kept as a reminder of a person, place or event.” Although often used synonymously, there is a difference and an asymmetry between a souvenir and a memento. All souvenirs are mementos, but not necessarily vice versa. One of the authors possesses, for example, a pair of salt and pepper shakers made from the burl of a redwood tree. They were prominently displayed along with about 200 other pairs of salt and pepper shakers in his grandmother’s collection proudly exhibited in a glass dining room breakfront and, as a young boy, he admired them so much that his grandmother gave them to him as a memento. They have little monetary value, but to him their intrinsic value is priceless because when he looks at them, a flood of wonderful memories of his dearly departed grandmother come to mind. Anyone else looking at those objects might shrug and wonder why they reside in a place of honor in his house. A souvenir, on the other hand, is usually tied to travel or tourism; not all mementos have such a geographically related connection. Souvenirs can be perceived of as tokens of memory during the moment of acquisition. Because they are acquired when one is removed from life’s usual activities, they are accorded status in the home. Spoons acquired on vacations can serve as mnemonic devices; the owner need only to glance and them and remember when and where they were purchased. That is why souvenir spoons are often shelved and displayed in special cases rather than used in everyday life (Lasusa 2007) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The souvenir spoons in this display case have special meaning to their owner and are thus displayed in a glass-fronted shadow box rather than serving any utilitarian function. (Source: Authors)

Souvenirs are essential pieces of evidence; proof of one’s travels. Souvenirs are an extension of that travel experience or location. And travel is valuable as a means to acquire cultural capital which, in turn, can increase one’s social status (Bourdieu 1983).

Souvenir Spoons in the United States: A Johnny-Come-Lately

Collecting silver souvenir spoons became very popular in Europe in the mid 19th century and by the late 19th century the fad, thanks in part to the popularity of the world’s fair in Paris (the Exposition Universalle of 1889) with its centerpiece of the Eiffel Tower, had finally diffused and taken hold in the United States (Larson 2003, 14-15). As was the case in Europe, the craze started first with wealthy Americans visiting Europe and eventually filtered down the social hierarchy to the bourgeoisie. These mementos “marked the names of foreign cities and famous landmarks they had visited” (Nebraska State Historical Society 2011).1

The first American souvenir spoon was produced by Galt and Bros., Inc. in Washington, DC in 1889 and included a profile of George Washington created to mark the centennial of his presidency (eBay Guides 2012). A matching spoon bearing the likeness of Martha Washington soon followed. As a newspaper article in the May 10, 1891 edition of the Omaha Daily Bee noted:

The season of summer traveling, so near at hand, will give a new impetus to the spoon fad. So great has been the demand the past season for souvenir spoons that all the larger cities of the United States…manufacture a spoon characteristic of the place or of some object of peculiar interest to the people of that place.

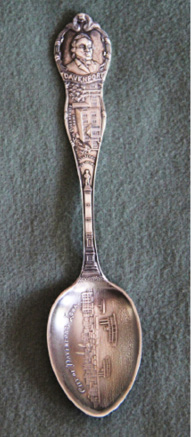

A year later, spoon collecting really took off when Seth F. Low, an American jeweler who had studied German souvenir spoons, created the Salem Witch Spoon for his father’s company, the Daniel Low Co. (Figure 2). Low described the spoon as featuring “the raised figure of a witch, the word Salem, and the three witch pins of the same size and shape as those preserved in the Court House at Salem.” Several thousand were sold and thus the era of the souvenir spoon as a representation of place and not just person began in earnest. An example of such a geographically specific souvenir spoon is this one from Davenport, Iowa (Figure 3).

Figure 2. This whimsical spoon played on stereotypes of the (in)famous Salem witch trials. Produced by the Daniel Low Company in 1891, it may have begun the spoon collecting craze in the United States and led to a spate of similar place-based collectables. (Source: Authors)

Figure 3. This busy spoon shows riverboats along the Mississippi River waterfront, a bust of Antoine LeClaire who founded the city, and the Soldiers and Sailors Monument on Brady Street and that is just the front of the spoon. On the reverse are ears of corn and a bunch of onions, a crop grown commercially in the area up through the mid 20th century. (Source: Authors)

The Silver Age of Souvenir Spoons and the Chicago World’s Fair

We discuss here in detail only a few of the estimated 503 souvenir spoons that were produced to celebrate the Columbian Exposition of 1893, the famous Chicago World’s Fair. But thanks to the publication of an illustrated volume by an avid Fair spoon collector, an overview of all the extant spoons is integrated into this article as well (McGlothlin 1985).

The timing of the Fair coincided with three other fortuitous events for souvenir spoon collectors: the drastic drop in the price of silver that started with the opening of silver mines in the West a couple of decades earlier (e.g., the Comstock Lode); the Panic of 1893 that kept the price of silver low even when the Western mines began to peter out; and the souvenir spoon collecting craze that started in Europe in the late 1880s, swept the nation during the Chicago World’s Fair and continued until WWI when the craze died out and silver prices began to escalate.

Although there was an opening day ceremony in October 1892 to coincide with the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s landfall in the Americas, costly delays led to a rather inauspicious beginning to the Fair that opened in May 1893 for a six-month run. But, by the end of October, the Fair was such a success that it was considered “to possess a transformative power nearly equal to that of the Civil War” (Larson 2003, xi). On Chicago Day designated by Mayor Harrison in early October 1893, city employees were given the day off and attendance at the Fair topped 700,000, the greatest peacetime gathering in the history of the city. In all, 27 million visitors attended the Fair at a time when the population of the United States was only 65 million and that of Chicago had just barely surpassed one million. Although Chicago had only a few thousand more residents than Philadelphia, it made Chicago, by 1890, the second largest city in the country. Still, the Fair developers and Chicago suffered from an inferiority complex. Despite its size, Chicago was still viewed as a parochial cow town by the elite in the East, especially in New York which had lost out in its bid to host the World’s Fair to that hog butchering frontier upstart. Until the time that daily attendance surpassed the world’s fair in Paris, Daniel Burnham and all the other architects involved with creating the White City – even Frederick Law Olmstead who designed the landscaping of the Fair – felt inferior to their European counterparts.

An Interpretative Analysis of the Fair’s Official Spoon: The Exotic Other

There is disagreement in the literature about which of the 503 spoons produced for the Fair was the “official” one (Stutzenberger 1971; McGlothlin 1985). Stutzenberger (1971), in a book that uses the souvenir spoon to illustrate significant events in American history, suggests that the official souvenir spoon of the Fair somewhat puzzlingly depicts the 1832 Massacre at Fort Dearborn of white settlers by a small band of rogue Potowatami in all its bloody and gory detail. On this spoon is a depiction of the Carl Rohl-Smith statue of the Massacre commissioned by George Pullman in 1893 (Figure 4). Despite the bravery of a tribal chief named Black Partridge to save some of the settlers, a spoon in his honor did not appear until the second Chicago World’s Fair, the Century of Progress, in 1933 (Figure 5). Such was the uninformed populist view of “Indian savagery” at the time, and the hugely popular acts of the contemporaneous Buffalo Bill Wild West Show that were performed just outside the official Fair site did nothing to disabuse Fair visitors of this negative stereotype.

Figure 4. The Carl Rohl-Smith sculpture of the Massacre at Ft. Dearborn that took place in 1832. One year later, Chicago was incorporated near the site of Ft. Dearborn. This statue, completed the same year as the Fair (1893), served as the model for one of the souvenir spoons that was declared the “official” spoon of the Chicago World’s Fair. (Source: http://indiana.typepad.com /fwob/2007/03 /no_safe_passage.html).

Figure 5. Chief Black Partridge of the Potowatami, brave defender of the settlers who were massacred while attempting to leave Ft. Dearborn for safer habitations, was finally honored with a commemorative spoon. But the spoon was produced for Chicago’s1933 Century of Progress, not the earlier Columbian Exposition of 1893. (Source: www.etsy.com).

The view of the foreign and exotic “other” was even more prone to stereotyping and exaggeration. Fair officials failed in their attempt to find recently discovered Pygmies from the Congo but they did manage to create a whole village of “cannibals” from Dahomey in the Midway area.2 Connecting Jackson Park, the square mile Fair site, with the more established and frequented Washington Park was a mile-long corridor known as the Midway Plaisance or simply the Midway. Some representations of the non-formal attractions of the Midway such as the Streets of Cairo and the African village exhibits were represented on souvenir spoons but these few spoons paled in comparison to the vast number that were produced to depict the formal buildings of the White City and to commemorate famous people and events, especially Christopher Columbus and his landfall in the Americas in 1492.

The Visage of Columbus Himself

There is great variation in the portrayal of Columbus on Fair souvenir spoons as there were no known portraits of him at the time of his voyage to the New World. In addition to Columbus himself, several spoons depicted important aspects of his landfall including the ships that brought him and the place from which he departed. In keeping with the cultural stereotype of the age, the Indians that Columbus and his landing party encountered were depicted as either cowering in the presence of the Conquistadors or offering tribute to Columbus as befitted his supposed status as conquering hero. Although the depictions of the landing party on the souvenir spoons varied between four and nine men, they were invariably outnumbered by the Indians in the motifs. The Indians appear cowed by the appearance of the cross and the sword conspicuously depicted on many of the spoons. The mottos on two of the spoons summarize the prevailing attitude of the age – “Taking Possession of the New World” (spoon #127) and “Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way” (spoon #218) (McGlothlin 1985, p. 82 and p. 126).

An Edifice Complex: The Great White City

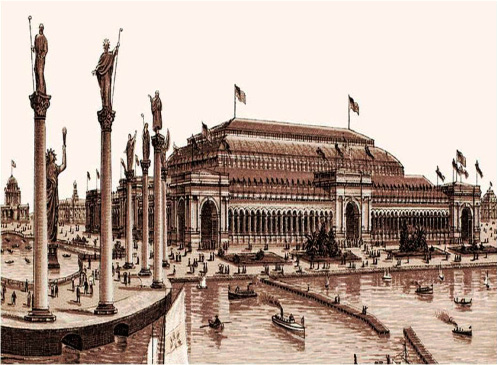

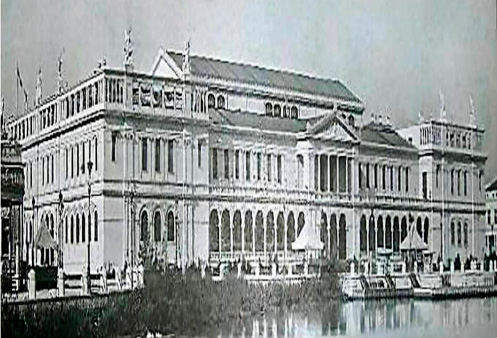

Many of the spoons (172 of 503) displayed representations of some of the more than 200 buildings constructed for the Fair including the largest building ever constructed at the time – the enormous Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building that appeared on 15 different spoons (Figure 6). The building depicted most often on souvenir spoons was the vertically oriented Administration Building that appeared on 31 spoons, perhaps because it was easier to depict in the spoon’s bowl than the other more horizontally oriented buildings of the White City (Figure 7). Surprisingly, the second most commonly depicted building was the Women’s Building that appeared on 24 of the spoons despite the fact that the building itself was rather peripheral to the main White City structures that surrounded Olmstead’s lagoon water feature (Figure 8). One explanation for the Women’s Building popularity as a spoon theme is that assumption that a great majority of souvenir spoon purchasers were women and such spoons were readily available for sale there.

Figure 6. An image of the largest structure under one roof at the time of the Chicago World’s Fair, the enormous Manufacturers and Liberal Arts Building of the White City, the main subject of at least 15 commemorative spoons struck for the Fair. (Source: www.fineartamerica.com).

Figure 7. An image of the Administration Building, an edifice that appeared more than any other – on at least 31 of the souvenir spoons produced for the Fair. It frequency on souvenir spoons may be attributed to its importance and locational centrality within the White City and its verticality which is easier to portray in the bowl of a souvenir spoon than the mostly horizontally oriented remaining buildings of the Fair site. (Source: www.avenuestereo.com).

Figure 8. An image of the Women’s Building, the only one designed by a female architect and second only in popularity as a theme on souvenir spoons (featured on at least 24 of them) to the Administration Building. The popularity of the Women’s Building as a spoon motif despite its peripheral location within the configuration of main buildings in the White City may have had to do with its availability for sale at that Building and the assumption that most purchasers of souvenir spoons would be women. (Source: www.rubylane.com).

The Sacred and the Profane? The White City and the Midway

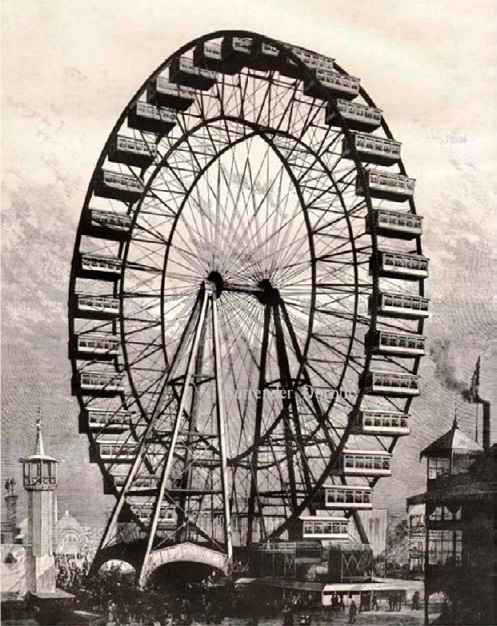

The geographic and cultural juxtaposition of the public buildings of the White City in the Beaux Arts classical tradition appealing to an elite, or at least a bourgeois, culture of the Gilded Age stood in stark contrast to the honky-tonk, faux exotic exhibits and concessions of the Midway Plaisance that appealed more to a mass culture. The geographer Barbara Rubin (1979) has previously discussed the disparity between those two cultural aesthetics. The lion’s share of the souvenir spoons commemorated either people, especially Columbus or his patron Queen Isabella, or buildings that comprised the White City. There were only four spoons of the 503 total that displayed scenes from the Midway, with the exception of the Ferris Wheel that appeared on ten spoons and came to represent the Chicago World’s Fair in the same way that the Eiffel Tower represented the early Paris Exposition (Figure 9). There are probably numerous reasons for this disparity between the many spoons depicting the formal areas and the paucity of those representing the more informal areas of the Fair. Silversmiths knew what the formal buildings looked like (or were to look like), but it would have been more difficult to capture in silver the frenetic energy of the Midway with its exotic cultures, foods, sights and smells. Visitors who were buying the souvenir spoons were certainly willing to view Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show just outside the Fair’s boundaries or the exotic belly dancing on display at the theatre in the Streets of Cairo exhibition area, but less likely to want to share those images with friends and neighbors for whom they were either buying the spoons as presents or wishing to recount their visit by relying on the spoons they had gathered.

Figure 9. An image of the giant Ferris Wheel constructed for the Fair. The Wheel appeared on at least ten souvenir spoons; far and away more than any other representation of Fair features on the Midway Plaisance that was not directly associated with the formal buildings of the White City. The same Ferris Wheel was later used for the St. Louis World’s Fair (The Louisiana Purchase Exposition) in 1904. (Source: www.pinterest.com).

We argue that the 24 Women’s Building souvenir spoons represent a transition between these two cultural worlds. Interestingly, the “official” Women’s Building spoon was topped not by Queen Isabella, but rather by the image of Mrs. Potter Palmer, wife of the owner of the famous Palmer House hotel and doyenne of Chicago society whose patrician cultural tastes in the fine and decorative arts were on display for those who wandered over to see them (Figure 10). More populist creations by women artists of the period were not included in the building that was designed by the only woman architect employed on the Fair’s staff – Sophia Hayden of Boston.

Figure 10. The top of a souvenir spoon depicting Bertha (Mrs. Potter) Palmer, wife of the owner of the famous Palmer House hotel and major figure in determining the content of the art and artifacts included in the Women’s Building of the Fair. (Source: www.2antiquesnavigator.com).

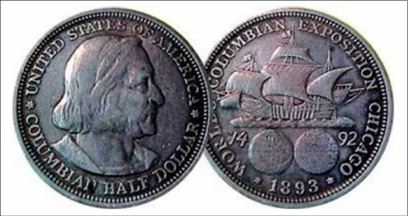

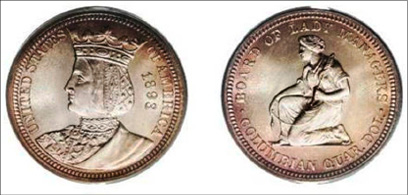

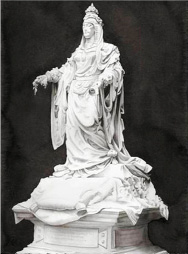

Another clue as to the nature of gender relations at the time was the fact that two commemorative medals were struck for the Fair – one of Columbus and the other with the image of his patron Queen Isabella (Figures 11 and 12). Neither medal sold particularly well, but the Columbus half dollar, sold for the price of one dollar at the Fair, was legal tender (now worth about $450 depending on condition to a coin collector). The Isabella “quarter dollar” medal, on the other hand, was not designated as a “coin of the realm”. To add further insult to injury, the Harriet Hosmer-sculpted statue of Queen Isabella that was designed to offer a female counterpoint to the emphasis on Columbus, was placed rather inconspicuously in the California State Building and viewed by few of the Fair goers (Figure 13).

Figure 11. A half-dollar coin with a representation of Christopher Columbus struck as legal tender in honor of the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. The coin did not sell well at the time of the Fair. Some were even incorporated into the bowls of souvenir spoons. (Source: www.coinquest.com).

Figure 12. A “quarter-dollar” medal with the visage of Queen Isabella, Columbus’s patron who bankrolled his voyage of exploration of the New World. Unlike the Columbus medal, the Isabella medal was not deemed to be legal tender. It was available for sale in the Women’s Building but it did not sell well during the Fair. (Source: coinweek.com and www.ha.com).

Figure 13. An image of the Queen Isabella statue sculpted by Harriet Hosmer. The impressive statue was not highly visible to Fair goers, being placed in the California State Building rather than more prominently and centrally displayed. (Source: www.artnet.com).

The Ferris Wheel: America’s Answer to the Eiffel Tower

Ten souvenir spoons tried to capture the enormity of the centerpiece of the Fair – the Ferris Wheel. Though its completion was delayed for almost two months after the Fair was officially opened in May, the Ferris Wheel was eventually an imposing revenue generator for the Fair. It stood 265 feet high, with 36 cars each weighing 13 tons and carrying 60 persons each which, when operating at full capacity, carried 20,000 passengers on the twenty-minute ride per day (Larson 2003, 261). The Ferris Wheel as a Fair icon was one of the few things on the Midway that was commemorated with a spoon. The Ferris Wheel was eventually disassembled and reconstructed for the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition (i.e., the St. Louis World’s Fair) before being scrapped.

Spoons That Leave One Wondering ‘Why?’

There are some souvenir Fair spoons that can only be classified as oddities such as representations of Leif Ericson, Joan of Arc, the Mormon Tabernacle and Egyptian pharaohs. In fact, the image of Leif Erickson appears on several spoons, one of which is purported to be the Fair’s most valuable collectible spoon. By 1893, it was common knowledge that Leif Erickson had arrived in North America more than 400 years prior to Columbus’s landfall, and the Mormon Tabernacle choir performed at the Fair, but why the images of Joan of Arc and Egyptian pharaohs? The latter may reflect the classical architectural revival of the period as well as the fascination with the exotic for those without the means to travel abroad and down the Nile. The reason of why Joan of Arc was commemorated is a bit of a mystery.

Spoons, Transformation and Commemoration

We have examined the souvenir spoon within the growing geographic literature on commemoration and memorialization (Dwyer and Alderman 2008). Souvenir spoons could be examined as well from the perspective of the cultural studies literature on the transformation of utilitarian objects (Basalla 1983; Bourdieu 1984). There are several categories of transformed utilitarian artifacts and the souvenir spoon would fall under the rubric of commemorative object. The means by which the transformation from utilitarian to commemorative object took place in the case of souvenir spoons is through the addition of ornamentation that resulted in the transfiguration of the artifact (Basalla 1982). Once transfigured, the souvenir spoon could no longer be considered banal.

The ornamentation added to a standard spoon form in order to create a souvenir can also be couched within the psychological theory of cognitive dissonance (Festinger 1957). From that psychological perspective, the souvenir spoon is a form that suggests utility. The disparity between the spoon as a common, merely utilitarian, object and the decorative souvenir spoon as a manifestation of the silversmith’s artistry creates cognitive dissonance that makes the transformed object distinctive. The dissonance is resolved by separating the artifact from the utilitarian domain and reserving it for some higher purpose. Most souvenir spoons are, therefore, displayed and venerated and not used on a daily basis.

The souvenir spoon, therefore, acts simultaneously as a trigger to remember journeys past and present, a way to enhance one’s cultural capital and gain insider’s knowledge, and as a forensic marker for the cultural geographer interested in representation and commemoration. We think it is sad that many of the silver souvenir spoons from the 1893 Columbian Exposition that come up periodically for sale on e-Bay are often priced on the basis of the grains of silver they contain rather than on their craftsmanship, the images they contain, the dioramas they display and vital forensic clues to the mindset of fin de siècle Chicago that they represent.

Concluding Remarks

Collecting souvenir spoons is still a niche hobby and those spoons still have stories to tell about people, places and things of memory and enjoyment. We argue that many of these spoons represent a form of commemoration and memory that can also be used as forensic evidence of lifestyle preferences. Designs on the spoons produced for the Chicago World’s Fair distinguished between the elite and bourgeois appeal of the Beaux Arts “white city” and the spatially separate and decidedly more working class Midway. There were many representative images on the spoons in addition to those of the formal buildings of the White City, such as a few of the Midway attractions and many visages of Columbus and/or his landing party in the New World. The points of purchase within the Fair site for spoons depicting women were somewhat peripheral and marginalized. This gender bias was evident whether the woman being honored was the image of the phoenix-like mythical Miss Chicago designed to memorialize the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 (Figure 14), the grand dame of Gilded Age Chicago society, Mrs. Potter Palmer, or a depiction of Queen Isabella. The treatment of female subjects by souvenir spoon silversmiths suggests a great deal about the marginalized role of women and gender relationships of the period in general.

Figure 14. An image of the mythical Miss Chicago with a crown on her head that reads “I Must”. This image was created after the Great Fire of 1871 and symbolized Chicago’s Phoenix-like rise from the ashes to become, by the time of the World’s Fair, the second largest city in the United States. The flames from the Great Fire are visible in the bowl of the spoon (Source: http://www.nlcspooncollectingclubs.org/NSCG/).

Likewise, the massacre of white settlers at Ft. Dearborn in 1832 by Potawatomi Indians as the featured tableau one of the “official” Fair commemorative spoons is indicative of status accorded to Indians at the end of the 19th century. The exotic “others” of the foreign exhibits on the Midway were accorded even less representation on Fair souvenir spoons than were Indians.

Three interrelated themes were stressed in this article – 1) an interpretation of the meaning of a sampling of the souvenir spoons produced specifically for the World’s Fair; 2) an examination of the difference in the cultural aesthetic of the two main areas of the Fair – the formal White City and the informal Midway as represented on the spoons produced for the Fair representing each milieu; and 3) cultural, geographical and psychological interpretations of the meaning of souvenir spoon collection and its importance for travel and tourism.

We hope that this article piques interest in the souvenir spoon as an element of material culture worthy of further study. Even though the faddish craze to collect souvenir spoons ended at the beginning of World War I, souvenir spoons collection is still a viable niche hobby. We would argue that modern souvenir spoons – mass-produced, kitschy, made of base metals and plastic rather than precious metals and often collected in representative sets – have lost most of the cultural capital their collection once engendered. Still, modern souvenir spoons are artifacts that are indicative of a different market segment than the spoons that appealed to the Chicago World’s Fair attendee and should still be examined as a forensic object of material popular culture.

Endnotes

1 The knowledge gained by travel even for the middle-brow crowds that attended the Fair is respected by their peers for two reasons – it is seen as “insider” (privileged) information about the elusive and mysterious “other” even if that “other” is as artificial/inauthentic as the Egyptian, Turkish or Dahomean country exhibits represented on the Midway Plaisance at the Fair. In the mid 19th century it was the elites who picked up souvenirs to memorialize their visits and thus acquire cultural capital in the process. Middle-class tourists of today travel and collect souvenirs for similar reasons – an attempt to outrank their peers (MacCannell 1976). Thus souvenir collecting can tell us something both about ourselves and our world.

2 At an especially offensive formal affair involving Fair officials and representatives from all the cultures represented at the Midway exhibits and villages, the menu included Roast Missionary a la Dahomey, west coast of Africa; Boiled camel humps , a la Cairo street; Hard boiled potatoes, a la Irish Village; and Fricassee of reindeer, a la Lapland (Larson 2003, 314).

References

Basalla, George. 1982. “Transformed utilitarian objects.” Winterthur Portfolio 17(4): 183-201.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste, R. Nice, transl. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1993. The Field of Cultural Production. New York: Columbia University Press.

Dwyer, Owen J. and Derek H. Alderman. 2008. Civil Rights Memorials and the Geography of Memory. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

eBay Guides. 2012. Your Guide to Buying Silver Souvenir Spoons. http://reviews.ebay.com/Your-Guide-to-Buying-Silver-Souvenir-Spoons?ug…

Festinger, Leon. 1957. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Kahn, Eve M. 2013. “Third-century cutlery released for auction. New York Times. May 24th, p. C23.

Larson, Erik. 2003. The Devil in the White City: Murder, magic and madness at the fair that changed America. New York: Vintage Press.

Lasusa, Danielle M. 2007. “Eiffel Tower key chains and other pieces of reality: The philosophy of souvenirs.”The Philosophical Forum. 38 (3): 271-287.

MacCannell, Dean. 1976. The Tourist: A new theory of the leisure class. Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press.

McGlothlin, Chris A. 1985. World’s Fair Spoons Volume 1: The world’s Columbian Exposition. Tallahassee, FL: Florida Rare Coin Galleries, Inc.

Nebraska State Historical Society. 2011. Souvenir Spoons http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/timeline/souvenir_spoons….

Rubin, Barbara. 1979. “Aesthetic ideology and urban design.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 69 (3): 339-361.

Stutzenberger, Albert. 1971. American Historical Spoons: The American story in spoons. Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle Company.

Contributors’ Biographies

Thomas L. Bell is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Geography at the University of Tennessee and Adjunct Professor in the Department of Geography and Geology at Western Kentucky University. He is an urban and economic geographer with an abiding interest in American popular culture.

Margaret M. Gripshover is an Associate Professor of Geography in the Department of Geography and Geology at Western Kentucky University. She is a cultural and historical geographer with regional specializations in the American South and . Her research interests include material culture, landscapes and the geography of sport, especially baseball and horses.

Return to top