The Mohawk Valley: New England Extended — A Field Trip Through Landscapes of Economic and Cultural Change and Diversity

Wayne Brew, Montgomery County Community College

Scott C. Roper, Castleton State College

Introduction

Physical Setting

The geology o f the Mohawk Valley is a story of several mountain-building episodes along with deposition of sediments in shallow inland seas. The formation of the super continent Pangaea uplifted the sedimentary rock deposits that created the Allegheny Plateau and the Catskill Mountains. To the north of the Mohawk Valley is the ancient pre-Cambrian rock of the Adirondacks. The sedimentary rocks include layers of sandstone, shale, and limestone along with commercial deposits of halite (salt) in the Syracuse area. The current landscape was shaped by the recurring advance and retreat of ice sheets during the Pleistocene leaving behind features such as glacial troughs, swarms of drumlins, glacial till, and the hummocky topography of recessional moraines. Most significant is the tremendous amount of water released when an ice dam blocking drainage of Lake Ontario failed, forcing water to flow through the Mohawk Valley to the Hudson River.

People

This region was settled around 12,000 years ago by the Haudenosaunee peoples, commonly known as the Iroquois. The Iroquois League may have formed as early as 1200, and was originally composed of the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, and Mohawk nations. A sixth nation, the Tuscarora, was admitted after 1720. The League found itself well situated in an area that transcended the waterways which allowed passage into the interior of the continent.

In 1609 Henry Hudson traveled up his namesake river to Albany. The Dutch liked what they saw, established Fort Orange in Albany, “purchased” a strip of land from the local natives, and established New Amsterdam in 1626. The colony attracted a diverse group of people and was fairly disorganized before the English arrived (1664). With their gun-boats, the English took the colony away from the Dutch and renamed it New York as a birthday gift for the Duke of York, the future King James II.

During the colonial period the Mohawk Valley was broken up into large manors which were contested by both Native Americans and the French. In the resulting conflicts between the French and English, the Six Nations sided with the British. Starting in 1754, the Mohawk Valley was the setting for many significant battles between the French and British known collectively in North America as the French and Indian War, and in Europe as the Seven Years’ War. The Six Nations remained loyal to the British, allowing the British to build Fort Stanwix and helping them defeat the French in 1763.

The post-war peace was still new when British migrants arrived in the area. The Boundary Line Treaty of 1768 attempted to settle disputes between the settlers and Native Americans. The treaty that was signed at Fort Stanwix by the Six Nations delineated European and Native American settlements to the south and west of the Mohawk Valley to the confluence of the Tennessee and Ohio Rivers. The new settlers did little to honor the boundaries set out in the treaty.

The War for Independence split the Six Nations; the Oneida and Tuscarora sided with the Americans. The Six Nations signed a treaty in 1784 that was not honored, and the war left them divided and weaker. They were not left much land in New York, but recently the Oneida Nation has opened the Turning Stone Casino and Resort, on land that was re-acquired from a private land-owner located just west of Fort Stanwix. The casino has become a popular destination, but has had its share of legal battles including the question if re-acquired native land can be considered the same as “reservation land.”

The Dutch

Between late 1792 and early 1793, agents working for the Holland Land Company, an unincorporated syndicate of investors based in Amsterdam, purchased roughly 3.6 million acres of land in central and western New York. Most of this land was in Genessee County, but the group also made purchases elsewhere, including in Oneida County in what is today the township of Trenton.

The first Dutch settlers came to Trenton (then called Oldenbarneveldt) in 1793. However, the lands were open to purchase by anyone, and the area soon was overrun with New England Yankees from Connecticut and Massachusetts. Although a few houses from the period of Dutch settlement remain in the village of Barneveld, the sheer number of Yankees at an early period made them, and not the Dutch, the region’s “first effective settlers.”

Palatine Germans

The area that now includes Little Falls, Fort Herkimer Church, and German Flatts was settled by Palatine Germans beginning in 1723. These migrants came originally from the Electorate of the Palatinate, a German region near the French border. In the late 1600s and early 1700s, this region was repeatedly invaded by France. The resulting famine, poverty, and high taxes, combined with an extraordinarily harsh winter and advertising by proprietors of English colonies in North America, caused thousands to Palatine Germans to migrate to England – many with the hope of finding passage to the Colonies – beginning in 1709. But the arrival of poor, uneducated, German-speaking peoples in England was controversial, and Parliament wanted to get rid of them, though the government had no desire to spend the money necessary to send all of them to North America. As a result, Parliament attempted to resettle them in Ireland and uninhabited areas of England, while only a small number headed for Newburgh, New York. When the migrations to Ireland and England failed and Palatines returned to London, the British government acquiesced and sent additional German migrants to New York.

Many Palatines settled along the Hudson River, where the Crown felt they would be useful in providing a buffer against the French and in producing stores for the British navy. Those settlements failed, and in 1723 the Colonial Governor of New York, William Burnet, allowed 100 heads of household to settle west of what today is known as Little Falls. Those families established scattered farms and communities such as German Flatts, Frankfort, and Palatine Bridge, and the German language remained prevalent in the region for about a century after initial Palatine settlement.

New England Extended

Both before and after the American Revolution, and especially after 1790, New England “Yankees” swept through the Mohawk Valley, many of them continuing westward through what geographer Donald Meinig called “the one great natural breach westward through the mountains.” A number of them remained in the Mohawk Valley, swamping many Dutch and German settlements. Royal grants allowed Massachusetts to claim large portions of New York, eventually forcing a compromise (1786) that allowed Boston speculators to sell the land, mostly to Yankees. But the land remained part of New York.

The Yankees who arrived in the Mohawk Valley brought with them the landscapes they had known in New England. Generally, these included townscapes that included Cape Cods, New England Larges, and Yankee Upright-and-Wings. Typically, one also found a meetinghouse set on common lands (in some places, these commons were later cleared of their buildings), English barns, and Greek Revival architecture. In some parts of New York the settlers built stone walls as well, though generally such features did not become part of the New England landscape until after the Revolution.

The Burnt-Over District

As Yankees extended their frontier, many kept their traditional religious beliefs. But for others, the freedom to experiment resulted in new religions and a fervor so great that this region is referred to as the Burnt-Over District. The most common goal of these new religions was to eliminate the hierarchy of middlemen and find a direct connection to God. Congregational and Presbyterian sects lost many members to Unitarianism, and even larger numbers to Methodist and Baptist congregations.

The more adventurous followed more radical offshoots of Christianity. William Miller, raised on the Vermont frontier, predicted the second coming of Christ in 1843 and again in 1844. His followers ended up quite disappointed, but to this day, a million persist as Seventh-Day Adventists. Vermont native Joseph Smith, Jr., found a set of golden plates near Mormon Hill, a drumlin north of Manchester, New York, forming the basis of the Mormon religion. Possibly the most interesting group is the Oneida Community, which we will be visiting on our trip and about which we provide additional information below.

Erie Canal

Native Americans used the Mohawk River to transport themselves and trade goods in canoes with several portage locations, including Little Falls and the “Great Carry” near Rome. European traders also used this route to Lake Ontario. The 200-mile trip took weeks and was limited to small boats. The first evidence of improvement came in 1730 just west of Utica with the digging of a 200-foot ditch through a meander to save a mile of river route.

Many interesting characters – too many to list here – helped build the Erie Canal. Dewitt Clinton did not conceive of the idea, but he was an early and dedicated promoter of it. Although Clinton held major political offices in New York, he was not a particularly adept politician. Clinton was not aware of the shifting winds and whims of a democracy, often finding himself at odds with the public. Despite his arrogance and political shortcomings, he was personally honest beyond reproach and for the most part ruled New York State. Clinton played the biggest part in the canal’s creation by financing it through a combination of private money and state-held bonds and promoting the political will necessary for such a huge project.

Ironically, the canal was not supported by any of the politicians in New York City, which was to be the greatest beneficiary of the completed project. Once the venture finally commenced on July 4, 1817 near Rome, it took only eight years to complete. This is an impressive feat given that the United States had no professional engineers. The construction of the Erie Canal set the pattern for future large construction projects by contracting out sections of the canal to local citizens, most of them farmers who hired necessary workers. Construction came in under budget, aided by new inventions for moving excavated material (improved wheelbarrows) and pulling large stumps with large wheels and pulleys that that cut down on labor costs. That the canal was constructed during a recession that also lowered labor costs, thereby reducing overall costs even as canal bonds remained a safe and dependable investment by the wealthy.

We will crisscross and see the Erie Barge Canal (completed in the early 20th century) and remnants of the nineteenth-century canal at different points along the trip. This area is somewhat unique because no locks were built from Herkimer to Oneida. It was the first part of the Erie Canal to be completed, thereby generating revenue to help finance the construction of the rest of the canal, and is the section that is referred to as “Clinton’s Big Ditch.” It also gave inexperienced engineers time to determine how the more difficult parts of the canal would be completed and experience to get it done.

Barneveld and Holland Patent

Barneveld and Holland Patent were settled in 1793 and 1797, respectively. Both communities were part of the original Holland Patent land grant that also includes much of the township of Trenton.

The first settlers in Barneveld were from the Netherlands. Holland Land Company agent Gerritt Boon settled first, in 1793; from his early experiences there, he believed he could create a successful year-round maple-syrup business. This venture failed when he found that sugaring is not possible by late spring. In 1798, with sagging land sales, Boon was succeeded as Holland Land Company agent by Adam Mappa. Under Boon and Mappa the company built a saw mill, a grist mill, a store, and an inn, and by 1810 Barneveld had become the center of trade in northern Herkimer County and parts of Oneida County. But the community grew slowly, from around 200 in 1804 to only 300 by 1876.

Migration from New England, particularly Connecticut, accounted for most of the settlement’s early population growth. In 1806, two years after the establishment of the Unitarian Church, Reverend John Sherman (grandson of Connecticut’s Roger Sherman, signer of the Declaration of Independence) became its pastor. Sherman created one of the early tourist spots in the region in 1822 when he opened the Rural Resort, which accommodated visitors wishing to see the local waterfall. The Octagon House (Figure 1) in Barneveld Village was built by Jacob Wicks in 1852. Previous to this, Wicks lived in Newport, where another octagonal house was constructed in 1849-50. His oldest son, William, grew up to be one of the early professionally trained architects in this area.

Figure 1. Barneveld Octagon House - The Octagon House in Barneveld Village was built by Jacob Wicks in 1852. Previous to this, Wicks lived in Newport, where another octagonal house was constructed in 1849-50. His oldest son, William, grew up to be one of the early professionally trained architects in this area.

Holland Patent Stone Churches Historic District

Like Barneveld, Holland Patent began as a holding of the Holland Land Company. The community was settled four years after Barneveld, mostly from Connecticut. As the settlers established saw and grist mills, they also set aside a 7.5-acre parcel of land for use as a public square. Like many New England greens at the time, this one was intended for the public’s use in education and religious observance. As a result, the first meetinghouse was constructed on the square in 1799. Because the meetinghouse was dominated by Presbyterians, the Baptists built their own church in 1812. The Presbyterians built their own church at the common’s center eleven years later.

The current village layout emerged after 1840. First, Unitarians built a Greek Revival church on the north side of Main Street on private property overlooking the green. This structure was home to St. Leo’s Roman Catholic Church from 1888 to 1965, and was converted to a residence in 1972. Then, a new stone Baptist church was constructed on the site of the old one in 1844. Built by local stonemason Charles Ackley in the Greek Revival style, the limestone church still stands on the northwest corner of the green, separated from the rest of the green by a road.

In 1843, Presbyterians constructed their own stone church to compete with the Unitarians and the Baptists. The church was built by Andrew Rockwell, a local builder known for designing and constructing stone bridges in the area. Built just south of the Baptist Church, the structure is still used as a Presbyterian Church. In fact, both buildings have been owned by the First Presbyterian Church of Holland Patent since 1949, and were connected by a classroom annex in 1965.

Finally, in 1858 a group of Congregationalist Welsh immigrants purchased a stone building south of the Presbyterian Church along Main Street and remodeled it as a church. The building is old for this area, having been built by one of the first landowners in the village and later used as a shop. It was used as a church until about 1950, and in 1970 it was remodeled into a residential property.

After the construction of the most recent Presbyterian Church in 1843-44, the village green was cleared of all of its buildings, including the earlier Presbyterian building and the old meetinghouse. By 1890 it resembled the idealized version of New England Extended – village green as park – that many people now associate with the region. Grass, trees, and shrubs were planted, and in the 1890s the community added a bandstand.

Northwest of the village green is the Holland Patent Railroad Station (Figure 2). Built between 1886 and the mid-1890s in the Eastlake/Stick style, the depot served the Utica and Black River Railroad and its successor, the New York Central, until 1960. This was an important rail line for local farmers, who used it to access regional and national cheese markets in the nineteenth century. Improved access to Holland Patent resulted in the community becoming a tourist attraction in the late nineteenth and early 20th centuries.

Figure 2. Holland Patent Railroad Station - The Holland Patent Railroad Station was built between 1886 and the mid-1890s in the Eastlake/Stick style. The depot served the Utica and Black River Railroad and its successor, the New York Central, until 1960.

Oriskany

On the way to Rome we will pass over an aqueduct that once carried the Erie Canal over Oriskany Creek and which is now used to support the road bridge (Figure 3). The village was founded in 1811, and developed both because of the location of the canal through town and as a result of the growth of the textile industry locally along the river.

Figure 3. Oriskany Creek Aqueduct – The remnants of an aqueduct that carried the Erie Canal over Oriskany Creek.

Oriskany Battlefield

The Oriskany Battlefield, located west of town, is the site of a Revolutionary War battle that pitted a group of Loyalists, Oneidas, and British troops against a militia group led by Nicholas Herkimer and composed mostly of Palatine German farmers and some Oneidas loyal to the Revolutionaries. Herkimer hoped to relieve the siege of Fort Stanwix. But his forces were ambushed, resulting in a large loss of life on both sides. The British brought in reinforcements, but the Americans countered this move when they sent reinforcements from Fort Stanwix, forcing the British side to disengage. The Americans lost 200 men while the British had an estimated 150 to 200 killed; this is believed to be the highest ratio of death to combatants of any Revolutionary War battle. The British technically won this battle, but ultimately it resulted in an unsuccessful siege of Fort Stanwix and an eventual British withdrawal. Herkimer was wounded during the battle and died soon after, but he was memorialized in the name of a town and a county. A monument was erected in 1884, and in 1962 the site was recognized as a National Historic Landmark. In 1964 it was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Rome Railroad Station

The New York Central Railroad built the Rome Station (Figure 4) in 1912 on the outskirts of town when the right-of-way was changed and elevated to accommodate the construction of the Erie Barge Canal. Amtrak ceded the station to the City of Rome in 1988 and proposed to stop rail service in 1996, but the city was able to secure federal monies to refurbish the station. The renovation project was completed in 2004.

Figure 4. Rome Railroad Station - The New York Central Railroad built the Rome Station in 1912. The renovation project was completed in 2004.

Rome

The location of Rome was long important as the western end of the navigable portion of Mohawk River. Here, Native Americans portaged their goods and canoes to nearby Wood Creek, which flowed to the west and was referred to as the “Great Carry.”

The British arrived in the area in the 1750s, building Fort Stanwix and Fort Bull to protect the area from French encroachment and Native American activities, particularly after the start of the Seven Years’ War. Fort Bull was destroyed in battle in 1756, and was replaced by Fort Stanwix two years later. The British abandoned Fort Stanwix sometime after the war’s conclusion in 1763. It would not be repopulated until 1776.

Rome’s early settlement was inhibited by Dominick Lynch, who purchased the land that would become Rome between 1786 and 1800 and refused to sell any of it to settlers, preferring to lease it instead. By 1819 the village at the center of Lynch’s property, Lynchville, was large enough to be incorporated as the Village of Rome – a name which was consistent with an early nineteenth-century trend to name places for classical people and locations. Rome did not become a city until 1870.

According to local legend, Governor De Witt Clinton symbolically turned the first shovelful of dirt for the Erie Canal in Rome in 1817. In reality, he was in New York City, celebrating the Fourth of July. And like Clinton, the canal itself never actually came to Rome, passing instead to the south of the community. As a result, Rome did not grow significantly until after 1839, when the first rail line was built through the village, and 1844, when the canal was relocated through Rome. The city became the site of the first successful cheese factory in 1841 (or 1851, depending on the source), and subsequently, businesses whose products ranged from textiles to a variety of metals and metal products called Rome home. Griffiss Air Force Base opened after 1942, further diversifying the economy.

The city fell on hard times in the 1960s. As the economy became more service-oriented, the city embarked on an ambitious plan of urban renewal. This plan resulted not only in the construction of a new shopping plaza and reconstruction of Fort Stanwix, but also in the destruction of many historic downtown structures.

Today, Rome’s economy is primarily white-collar. Even Griffiss Air Force Base has closed; in fact, the base was used for the ill-fated Woodstock ’99 concert. However, since the 1990s a number of local groups and residents have worked to save what is left of the town’s architectural heritage, and to highlight the town’s history in an attempt to improve the city’s sense of community.

Fort Stanwix

Fort Stanwix was built in 1758 by the British to protect a crucial transportation portage called the Oneida Carry, which connected the Mohawk River and Wood Creek, and named for British Commander General John Stanwix. After the end of the French and Indian War the Boundary Line Treaty was negotiated and signed at the fort. The British abandoned the fort, and during the American Revolution the structure was repaired and re-named for General Philip Schuyler. In August 1777 the British, along with loyalists and Native Americans, lay siege to the fort for 21 days, without success. The Americans abandoned the fort in 1781, and by the mid-nineteenth century warehouses and industrial buildings covered the site.

In the early 1920s the combination of a declining local economy and the realization of the importance of the site led local citizens to establish the legacy of the fort. The sesquicentennial anniversary of the siege was celebrated in 1927. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Fort Stanwix Act in 1935 to recognize the site as an important part of United States history and establishing it as National Monument. Urban renewal in the 1960s cleared the area of commercial buildings, and the City of Rome donated the property to the National Park Service which started archeological investigations in the early 1970s. The looming Bicentennial of 1976 ensured that the fort was rebuilt in time for the celebration. Fort Stanwix and Fort Necessity are the only two sites from the French-Indian war that are maintained by the National Park Service.

Urban Renewal and Remaining Downtown Structures

As in much of the Mohawk Valley, urban renewal made its mark on Rome in the 1960s and early 1970s (Figure 5). The reconstruction of Fort Stanwix was a unique development, but urban renewal also stripped much of downtown Rome of its historic structures in the name of convenience. Between 1960 and 1979 the city and private companies constructed parking garages, a new city hall, a shopping plaza, three new bank buildings and other commercial structures, and elderly housing. Among the few older buildings remaining and restored in the old downtown are the Capitol Theater (1928), a 1700-seat performing-arts center operated as a movie house until 1974; the Sears Gas Station (1930), constructed by the Sears Oil Company and functioning as a museum since 2005 (Figure 6); the Oneida County Courthouse (1851); and the Rome Post Office Building, home to the Rome Historical Society since 1980.

Figure 5. Rome Mural – Much of downtown Rome was torn-down during urban renewal. What remains is parking and a mural.

Figure 6. Sears Oil Company Gas Station – This structure was built in 1930 and was restored and now operates as a museum.

Oneida

Oneida is the only city in Madison County. Unlike Rome, Utica, and Little Falls, the city was not a victim of urban renewal in the 1960s and 1970s, and so retains a much greater proportion of its historic architecture than the aforementioned cities.

Americans of European ancestry first settled the area when it was part of the town of Lenox. The first store is believed to have been constructed near here in 1818; the name of the store owner, Van Epps, suggests a Dutch presence. The area remained sparsely settled until the 1830s, when the construction of the Erie Canal feeder and the establishment of a railroad stop there led to an expansion of industry and the incorporation of the Village of Oneida in 1848. Subsequent years of friction between Oneida and Lenox led to the establishment of a new Town of Oneida in 1896, which became the City of Oneida five years later.

Oneida became a significant manufacturing center in the late nineteenth century. Subsequently, the Barge Canal and the later New York State Thruway both bypassed the city, rail service ended, and manufacturing plants closed or moved away. Retail business has moved from downtown to Route 5, where shopping centers have sprung up since the early 1960s. As a result, Oneida is primarily a residential community that functions as a central place for shopping, health care, and financial services. And while many local residents commute to Utica and Syracuse for work, local businesses continue to employ local residents as well.

The Oneida Community Mansion House

Upstate New York has been referred to as the Burnt-Over District to describe the religious fervor generated there during the first half of the nineteenth century. The site we will visit is the Oneida Community, which was founded by John Humphrey Noyes and his band of New England transplants. Their commune was based on the premise of Perfectionism, that one could lead a life free of sin. Perfectionism was practiced by several groups, but starting in the 1830s Noyes aggressively pursued and codified his own version of it. Noyes initially set up shop in New Haven where he teamed up with a dismissed pastor to publish his version of Perfectionism. He traveled widely, but eventually he ended up in his hometown of Putney, Vermont, where he converted his sisters and brother to his ideas. In 1838 Noyes married, and within two years he set up his first commune consisting of family members and a small group of converts. Noyes and his converts, who called Noyes’s philosophy “Bible Communism,” were convinced that he was an agent of God.

By 1845 Noyes became convinced that the final resurrection will come about more quickly if the commune adapted “complex marriage.” In this system, commune members could choose multiple partners so long as Noyes approved. To avoid unwanted pregnancies and illegitimate children he enlisted the male members to practice “male continence,” or the skill of not ejaculating during sex. Noyes was arrested in 1847 when the authorities in Putney got word about what is going on. At first he viewed the trial as an opportunity to espouse his philosophies, but a trusted legal advisor convinced him to get out of Vermont before a mob meted out their form of justice to the commune. Wisely, Noyes moved his operation to Oneida, New York, in 1848.

For the most part the Oneida Community, as it came to be known, was left alone and flourished. Noyes maintained firm control over complex marriage and added the practice of mutual criticism, which allowed members to air their grievances with any other member. Noyes also implemented practices whereby the young women were introduced to sex by the older men who have perfected male continence, while the young boys who had not mastered this technique were introduced to sex by post-menopausal women. Noyes and his trusted allies approved the “interviews,” as these liaisons were called, as well as whether or not women would have babies. Over time Noyes became enamored with eugenics and implemented a program that he called stirpiculture that paired people chosen for their spiritual accomplishments, not physical attributes.

With around 300 members at its peak in 1878, one might say that this experiment was successful. But the system became heavily bureaucratic, with over 20 committees and almost 50 administrative sections. The Oneida Community was able to franchise the operation and set up communes in Connecticut, New Jersey, and two in Vermont. All of the branches were closed by 1854 except for the one in Wallingford, Connecticut, which closed down when it was damaged in a tornado in 1878. When a professor at nearby Hamilton College clamored to arrest Noyes for statutory rape, Noyes fled to Canada, catching his escape train in Holland Patent. Noyes had been grooming his son to take over for him, but the younger Noyes was an off-and-on agnostic and did not possess the organizational skills of his father. Perhaps as a result, many in the community were against his leadership. The community dissolved in 1881. Noyes suggested in 1879 that complex marriage should be abandoned and the couples sorted themselves out and entered into conventional marriages. The community built a house in Canada with a view of Niagara Falls for Noyes to live out his final years with trusted allies and visitors.

Prior to the Oneida Community’s breakup, the group set up manufacturing interests to support it. The community began by producing animal traps, and eventually branched out to silverware, cane hats, silk, and leather bags. These interests generated income, a fact which allowed the community to have such a long run. During the World Wars, Oneida Limited thrived making ammunition casings and surgical instruments. By the late 20th century it focused on flatware, for which it is famous to this day. Today, however, the organization outsources all of its production.

The Oneida Community Mansion Building (Figure 7) was constructed from 1862 to 1914 and reveals the different architectural styles popular during this period. It was listed as a National Historic Landmark in 1965 and houses the Oneida Community Museum along with apartments.

Figure 7. The Oneida Community Mansion House - The Oneida Community Mansion Building was constructed from 1862 to 1914 and reveals the different architectural styles popular during this period. It was listed as a National Historic Landmark in 1965 and houses the Oneida Community Museum along with apartments.

Vernon Center

Vernon was settled in 1798 by migrants from Winchester, Connecticut. The six-acre Vernon Center Green was laid out in 1799, and like the green in Holland Patent, it reflects the New England-based settlement ideals of the community’s founders: it was to be held for public use, as well as the erection of buildings for Protestant religious worship and education.

From an early date, the green was the site of two churches, the last of which was removed in 1858 as a “new” ideal – that of the central-green-as-park – swept through the region. In the 1860s, after all buildings had been removed, trees were planted on the green, and in 1901 a gazebo was constructed on the property. The two churches at the north end of the green were constructed in Federal and Greek Revival styles in the 1820s-30s, but remodeled in the 1880s to reflect Romanesque and Gothic Revival styles popular at that time.

Clinton

The Village of Clinton was established in 1843 and named after George Clinton, De Witt’s uncle. The village was established by Yankees who placed a great importance on education. By the early 1800s many schools were established and Clinton was known as a village of schools. Just outside of Clinton is Hamilton College, which was established in 1812. Two major fires in 1862 and 1884 destroyed the business districts, so many of the buildings seen here today were built after the canal shut down in 1878.

The Chenango Canal was completed through Clinton in 1837, connecting Binghamton and Utica. The canal allowed for the transportation of iron ore mined near Clinton to be taken cheaply to the nearby Franklin Springs furnace to be smelted into pig iron. It also encouraged the establishment of woolen textiles and Clinton became a port for the export of local produce including fruits, vegetables and hops. In the mid-1800s hops were grown throughout this region and by the Civil War this region produced 90 percent of the hops grown in the United States. A specialized barn to store and process the hops was developed with a distinctive high pyramidal roof used as kiln (or two, one at each end). By the early 20th century much of the hop production shifted to the West Coast were the picking was mechanized, resulting in lower prices. At the same time the New York crop was hit hard by mildew (1909) and aphids (1914), which effectively brought hop production to an end in this region. Unfortunately, few of these distinctive barns still exist.

Utica

Utica was founded before the completion of the Erie Canal. A sand bar that formed from deposits from Reall Creek created a shallow crossing for fording the Mohawk River which gave this location an early locational advantage. Fort Schuyler was constructed in this location during the French and Indian War in 1758 and Utica was incorporated as a village in 1798. Roads were constructed to connect Utica in all directions including the Seneca turnpike which ran through the village.

The completion of the middle section of the Erie Canal in 1819 spurred growth that only accelerated with the full completion of the canal in 1825. The creeks that drained into the Mohawk provided water power for early industry. The completion of the Chenango Canal in 1837 brought the transport of coal from Pennsylvania, thereby allowing Utica to grow as a transportation and industrial center. The building of the railroads in the middle and late nineteenth century fueled the growth.

Utica incorporated as a city in 1823 and by 1850 was the 29th largest city in the United States. The population peaked at over 100,000 in 1930, remained stable until 1960, and then declined with the closing of the industry and the growth of the suburbs. Utica experienced a small increase in population to 62,000 in 2010.

Transportation and industry attracted many migrants to Utica: New Englanders, Welsh, Irish, Germans, Italians, and Polish. The story of the ethnic groups that settled in Utica is well documented by Allen Noble. In the late 20th century Utica became a destination for many migrants from conflicts and political upheavals including Vietnamese, Cambodians, Laotians, Burmese (Karin), Russians, and the largest group Bosnians. These migrants now comprise 12 percent of the population and were attracted by available refugee relief and the low-cost and available housing.

Union Station

The Utica Union Station (Figure 8) was built in 1914 in the Beaux Art Style and by the time it was added to the National Register in 1975 it was in bad condition. Oneida County obtained ownership of the station from Penn Central in 1978 and secured funding to refurbish the station. In 1979 the station was designated as the official terminal for the Lake Placid 1980 Winter Olympics. A series of staged remodeling projects have successfully restored the station that you see today.

Figure 8. The Utica Union Station was built in 1914 and was added to the National Register in 1975. The restored interior seen in the photograph is the end result of several restoration projects starting in 1979.

German Flatts

German Flatts was settled in 1723 by Palatine Germans. The area north of the river was originally known as German Flatts, and featured the original Palatine German village. Much of the area south of the river was owned by the Herkimer family and was the location of Fort Herkimer. However, when the lands were surveyed, a misunderstanding led to the mislabeling of the survey map, and the names were switched. Today, German Flatts, which was established in 1788 and laid out in 1791, is south of the river, and Herkimer is to the north.

Although agricultural for most of its history, German Flatts saw several villages grow into important industrial centers. Among these is Ilion, home of the Remington Arms Company since 1816, and which grew in part because the Erie Canal made distribution of firearms easier after 1825. As it grew, the Remington family branched out into other areas, including the manufacture of typewriters, sewing machines, and agricultural implements. Mohawk, too, became an important manufacturing center, known mainly for its knit goods.

Fort Herkimer Church

Fort Herkimer Church (Figures 9a and 9b) is one of the oldest churches in the state of New York, and the oldest building in Herkimer County. Construction by Palatine German settlers began in 1753. The limestone structure was only partially finished in 1754 when war broke out, as a result of which the church was fitted with over 30 gun ports and with buttresses projecting from its corners. It is the only remaining structure from the Fort Herkimer complex that once occupied the site.

Figure 9 a and b. The exterior (top) and interior of the Fort Herkimer Church.

Construction resumed in after the war ended in 1763, and the structure was completed in 1767. From 1812 to 1814 the church was extensively remodeled; it grew to two stories with a gallery on three sides, the pulpit was moved from the north to the east end of the building, and the entrance was relocated from the south to the west end. At some point during its history the gallery was closed off and a ceiling installed, but the ceiling was removed during a period of extensive renovation that began in 1976. The building was listed to the State and National Registers of Historic Places in 1972, and today is owned by the Montgomery Classis of the Reformed Church in America.

Little Falls

Palatine Germans settled in Little Falls in the 1720s. The area soon became a portage stop for travelers wishing to get around the 40-foot-high falls, and in 1795 the Western Inland Lock and Navigation Canal opened.

In the early nineteenth century Little Falls sat in the midst of the North American “breadbasket,” though that designation disappeared after the opening of lands in the West and the completion of the Erie Canal. By the 1840s, cheese had become an important commodity, resulting in the construction of milking barns throughout the region. In 1861 the city’s first open-air cheese market opened near the Herkimer County Bank, and a decade later the Board of Trade established the Cheese Market, which essentially controlled the price of cheese in the United States.

Grist, paper, and textile mills, taking advantage of the abundant waterpower afforded by the river, arrived in the early nineteenth century. But the construction of the Erie Canal (Figure 10) and the coming of the railroads caused industry to expand, and with this expansion came ethnic diversification: Irish and German immigrants arrived in the mid-1800s, followed by those from eastern and southern Europe.

Figure 10. Erie Canal Lock Remnant at Little Falls – East of Little Falls an Erie Canal Lock can be found.

In 1912, several states – including New York – enacted legislation to reduce the workweek in textile factories, a move which typically also reduced the amount of each employee’s weekly take-home pay. As a result, the year saw many strikes across the United States, including one at Little Falls, where employees worked 60 hours per week for very low wages. And like in other cities in the Northeast, the predominantly immigrant workforce from eastern and southern Europe sought help from the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), or “Wobblies.” Founded in 1905 by “Big Bill” Haywood, Eugene Debs, and others, the IWW hoped to organize workers into “one big union” – rather than into “locals” based on occupation, as the rival American Federation of Labor had done. In fact, the IWW hoped to reorganize the entire world along socialist-anarchist principles, taking power and wealth out of the hands of the few and redistributing it equally among workers.

In Little Falls, laborers walked off the job in the Phoenix Mill on October 9, 1912. Soon, more than 2,000 workers were on strike, aided by IWW organizers including Bill Haywood. Radicals congregated on Bleecker Street, organized strikes and demonstrations, and solicited donations and organized relief efforts for strikers. Strike leaders were arrested and jailed, and local police attacked picketers on several occasions. The walkout finally ended on January 3, 1913, after mill owners acceded to worker demands for a 54-hour work week at the previous 60-hour pay.

Downtown Little Falls and Urban Renewal

From 1962 and into the 1970s, Little Falls undertook a major urban renewal project which covered 73 acres of the central business district (Figures 11a and 11b). In 1969, the completion of a $1 million shopping center and a $1 million public housing high-rise building for elderly residents marked the end of the first phase.

Figure 11a. Downtown Little Falls – A section of business fronts has been restored in downtown Little Falls.

Figure 11b. Downtown Little Falls – The other side of the main street in Little Falls fell victim to urban renewal to be replaced by a shopping center, which itself was demolished in 2013.

A second phase commenced in 1970 with the construction of a motel-restaurant complex, an automotive center, a commercial center, and an industrial development. The city also opened two new arterial roads through town, one of which resulted in the destruction of houses on Hancock and West Main Streets. These links were connected to the New York Thruway with the opening of an interchange in the early 1970s.

Herkimer County Bank/Little Falls Historical Society

Herkimer County Bank was the first bank in Herkimer County. Constructed in 1833 at a cost of $3000, this Greek Revival building (Figure 12) became the center of the national cheese trading market in the 1870s. In 1964 the building was slated for demolition as part of the proposed urban renewal of the area – apparently, the new bank building constructed nearby needed even more parking than what eventually was allotted. In response, a group formed to save the building, resulting in its listing to the National Register of Historic Places in 1970 and its purchase by the Little Falls Historical Society in 1977. After a seven-year renovation. the building re-opened in 1985 as the Society’s museum.

Figure 12. Herkimer County Bank – This 1833 building was saved in the nick of time and now houses the Little Falls Historical Society.

Little Falls Historic District

Perhaps in belated reaction to the loss of a large portion of the downtown, in 2011 the community saw the listing of the Little Falls Historic District. The district consists of 347 contributing structures over more than 90 acres. It includes buildings constructed in Early Republic/Federal, Greek Revival, Italianate, Italian Villa, Second Empire, Queen Anne, Colonial Revival, Classical Revival, Tudor Revival, and Bungalow/Craftsman styles.

James Sanders House (546 Garden Street)

Erected in 1827, the two-story, brick, Federal-style, center-hall-plan house was constructed at the head of North Mary Street, overlooking the business district. It was constructed for James Sanders, a building contractor who worked on the construction of the Erie Canal in 1823. The canal created a building boom in Little Falls, and as a builder, Sanders was able to take advantage of that condition. He is responsible for the construction of numerous mills, residences, and public buildings in the city.

Canal Place (South Ann Street-Mill Street Historic District)

The mills, depot, and business blocks that make up Canal Place are all that remain of a complex that emerged along the old Western Inland Lock Navigation Canal (1795). The extant buildings include a four-story, stone-masonry woolen mill constructed in 1839 (Figure 13a) which is the oldest industrial building in Little Falls; a stone-masonry textile mill built in 1855 as part of the Mohawk Mills; two brick commercial blocks on Mohawk Street (1870 and 1885); and a three-story brick factory and connected wood-frame carriage works. The steel bridge dates from about 1920, and the former New York Central Railroad passenger station from 1894. The district also includes a brick apartment building containing Greek Revival storefronts, constructed in 1835 and which lined the Little Falls canal basin and aqueduct (Figure 13b). This feature is rare, and attests to the influence of the Erie Canal on local architecture and commerce.

Walking toward the south, if you stand on the bridge over the Mohawk River, you may see a tall pile of stones (Figure 13c). These stones are all that remains of a 214-foot-long aqueduct, or “bridge for boats” that once carried water and boats over the river between the Erie Canal to a boat basin northeast of Canal Place. The 16-foot-wide aqueduct was built in 1822-27, and consisted of a 70-foot arch with two smaller arches on either side. After the walls of the aqueduct burst in 1881, it was abandoned. The central arch – which was all that remained of the original structure after 1928 – finally collapsed in 1993.

Figure 13a and 13b. Canal Place in Little Falls – Former textile mills in Little Falls are now used for retail and residences (top). Commercial buildings on Mohawk Street (bottom).

Figure 13c. Little Falls Aqueduct – All that remains of a 217-foot aqueduct that carried the Erie Canal over the Mohawk River in Little Falls.

Herkimer

As we return to Utica, we will drive along the north side of the river. Before we arrive in Herkimer, you may catch a glimpse of a Russian Orthodox cemetery and church (c. 1964), the latter constructed by descendants of Russian and Carpatho-Rusyn migrants (Figure 14a). We will pass through an early 19th century village in which much of the development occurred during the automotive age, and we will see the post-New York Thruway decline as seen in the adaptive reuse of a motel as a church.

By 1797, Herkimer village could boast a courthouse, a jail, and a population of about 250. In the early nineteenth century, the community served as a relay station on local stage coach lines, and also developed a handful of small industries. The completion of the Erie Canal near Herkimer in 1825 improved the local economy significantly, and the subsequent construction of the Herkimer Hydraulic Canal in 1833 provided waterpower for local industries.

Figure 14a. Russian Orthodox Church near Herkimer – This structure was built in the 1960s to serve the local Carpatho-Rusyn migrants.

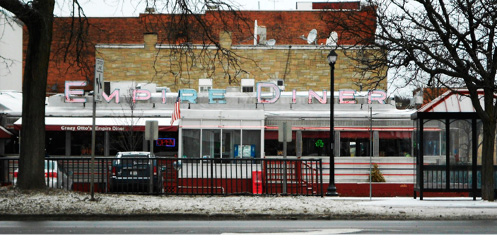

In Herkimer village, the jail (1834), county courthouse (1873), post office (1934), Suiter Building (1884), and Reformed Church (1835) are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Also notable is Crazy Otto’s Empire Diner (Figure 14b), a 1952-model prefabricated diner (serial number 330) constructed by Mountain View Diners Company in New Jersey.

Figure 14b. Empire Diner – A 1952 Mountain View Diner in Herkimer.

Outside the village in the town of Herkimer, the Palatine German Frame House (built after 1750) is also on the National Register as an early surviving example of Palatine German architecture.

References

“The Battle of Oriskany – Setting the Stage.” http://www.nps.gov/history/NR/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/ 79oriskany/79setting.htm. Last accessed June 23, 2014.

Bernstein, P. 2005. Wedding of the Waters: The Erie Canal and the Making of a Great Nation. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Briggs, J. 1972. An Italian Passage: Immigrants to Three American Cities, 1890-1930. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Canfield, W., and J. Clark. 1909. Things Worth Knowing about Oneida County. Utica, NY: T. J. Griffiths.

Carden, M. 1998. Oneida; Utopian Community to Modern Corporation. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Cooney, E., editor. 1970. Little Falls, New York Diamond Jubilee Celebration, 1895-1970. Little Falls, NY: no publisher.

“Crazy Otto’s Empire Diner.” http://www.crazyottosempirediner.com/. Last accessed September 21, 2013.

Dunn, B. 2012. “Worker’s Rights: Series of events planned to commemorate 100-year-old Little Falls Textile strike.” The Utica Phoenix, July 20; http://uticaphoenix.net/workers-rights-series-of-events-planned-to-commemorate-100-year-old-little-falls-textile-strike/, last accessed September 4, 2013.

“German Palatines.” Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_Palatines. Last accessed October 1, 2013.

“The Great American Train Stations: Utica, New York.” http://www.greatamericanstations.com/Stations/UCA. Last accessed October 1, 2013.

“History and Culture – Fort Stanwix National Monument.” http://www.nps.gov/fost/historyculture/index.htm. Last accessed June 23, 2014.

“H.P. Sears Oil Company, Inc.” http://hpsearsoil.com/. Last accessed October 1, 2013.

“July 8th: Matilda Robbins and the I.W.W.” Jewish Currents: Activist Politics and Art, http://jewishcurrents.org/july-8th-matilda-robbins-and-the-iww-19140. Last accessed October 1, 2013.

Klaw, S. 1993. Without Sin; The Life and Death of the Oneida Community. Penguin Books New York, New York

Koeppel, G. 2009. Bond of Union; Building the Erie Canal and the American Empire. Philadelphia: Da Capo Press.

Leonard, P. 2007. Rome Revisited. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing.

“Little Falls Historic District, Little Falls, New York.” http://www.oprhp.state.ny.us/hpimaging/hp_view.asp?GroupView=103880. Last accessed October 1, 2013.

Madison County Hop Heritage Trail Guide, http://www.madisontourism.com/trail_hop.pdf. Last accessed October 1, 2013.

McCullough, D. 2011. The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris. New York: Simon and Schuster.

McFee, M. 1993. Limestone Locks and Overgrowth: The Rise and Descent of the Chenango Canal. Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press Ltd.

Meinig, D.W. 1993. The Shaping of America: A Geographical Perspective on 500 Years of History, volume 2: Continental America, 1800-1867. New Haven: Yale University Press.

No author. n.d. “A Brief History of the Fort Herkimer Church.” Pamphlet, courtesy Donald Fenner.

Noble, A.G. 1999. An Ethnic Geography of Early Utica, New York. Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press, Ltd.

Oneidacity.com. http://www.oneidacity.com/Our%20Community/our%20community.html. Last accessed October 1, 2013.

Oneida County Historical Society. http://www.oneidacountyhistory.org/spotlight/vernon/vernon.asp, accessed September 21, 2013.

Perkins, S., and C. Hopson. 2010. German Flatts. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing.

_______. 2010. Little Falls. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing.

Rome Capitol Theater. http://www.romecapitol.com/. Last accessed October 1, 2013.

“Rome, NY Train Station a Treasure and a Convenience.” Examiner.com, http://www.examiner.com/article/rome-ny-train-station-a-treasure-and-a-convenience. Last accessed October 1, 2013.

“The Six Nations Confederacy during the American Revolution.” http://www.nps.gov/fost/historyculture/the-six-nations-confederacy-during-the-american-revolution.htm. Last accessed October 1, 2013.

Snyder, R. 1979. “Women, Wobblies, and Workers’ Rights: The 1912 Textile Strike in Little Falls, New York.” New York History 60:1 (January) 29-57.

“South Ann Street-Mill Street Historic District, Little Falls, New York.” http://www.oprhp.state.ny.us/hpimaging/hp_view.asp?GroupView=102318. Last accessed October 1, 2013.

Vang, R. 1996. “The Past, Present, and yes, Future of the Hops Industry.” Upstate Alive Magazine, http://www.upstatechunk.com/beer/hops/nyhistory.htm. Last accessed October 1, 2013.

“Vernon Center Green Historic District, Vernon, New York.” http://www.oprhp.state.ny.us/hpimaging/hp_view.asp?GroupView=6099. Last accessed September 21, 2013.

Vescio, P., and the Rome Historical Society. 2004. Rome. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing.

Village of Barneveld, NY. “History.” http://villageofbarneveld.org/content/History. Last accessed October 1, 2013.

Village of Herkimer, NY. “History.” http://village.herkimer.ny.us/content/History. Last accessed October 1, 2013.

Village of Holland Patent, NY. “History.” http://village.holland-patent.ny.us/content/History. Last accessed October 1, 2013.

Village of Oriskany, NY. “History.” http://villageoforiskany.org/content/History. Last accessed October 1, 2013.

Visser, T. 1997. Field Guide to New England Barns and Farm Buildings. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.

Vogt, E. 2011. Bicentennial Celebration 1811-2011: Little Falls, New York. Little Falls, NY: no publisher.

Woodard, C. 2011. American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America. New York: Penguin Books.

Contributor Biographies

Wayne Brew is Assistant Professor and Coordinator of Geography at Montgomery County Community College in Blue Bell, Pennsylvania. He received B.S. degrees in Earth Science (Geology) and Geography from Penn State University and an M.A. in Geography from Temple University. Research interests include the cultural landscape, vernacular architecture, historical and urban geography.

Scott Roper is Associate Professor of Geography and coordinator of the geography program at Castleton State College in Vermont. He is currently working on a project relating baseball in early twentieth-century Manchester, New Hampshire, to immigration, Progressive politics, material culture, and the rise of labor movements.

Return to top