The Distribution and Forms of Rural Gasoline Stations in South-Central Pennsylvania

Paul Marr and Claire Jantz, Shippensburg University

Introduction

As the number of automobiles increased in the post-WWII era, businesses that serviced automobiles spread across the landscape. In particular, petroleum companies scrambled to meet pent-up demand and built gasoline stations or leased franchises at a tremendous rate. Road improvements and the development of the interstate highway system fundamentally altered mobility patterns, and it is no surprise that the location of gasoline stations mirrored these changes in accessibility. One of axioms of locational theory is that supply will follow demand, and as the new age of automobility altered the demand landscape, gasoline retailing followed suit, concentrating heavily in the urban centers and developing suburbs. There is, however, a third segment of the demand landscape – rural populations.

Unlike their urban / suburban counterparts, rural populations cannot rely on concentrated demand to ensure supply. Their diffuse nature makes servicing rural populations particularly challenging for companies and frustrating for residents. In a situation such as this tried and tested service strategies fall short and new or hybrid strategies are often adopted. We believe that this was the case with rural gasoline stations, with new and unique forms of gasoline retailing occupying the dominant role in rural servicing. Our intent in this study has been to document the distribution and forms (e.g. the physical s of the station) of rural gasoline stations in a small number of counties in south-central Pennsylvania. While gasoline stations were most highly concentrated in the urban setting, stations outside of the cities and towns formed an important part of the rural landscape. It is these rural gasoline stations that are of particular interest to this research, and we believe these stations form an important subset of American gasoline stations that merit investigation. Our goal here, then, is to determine how these rural station types fit into the boarder station form categories proposed by Jakle and Sculle (1994) in their book The Gas Station in America. Placing rural gasoline stations within this broader context is important in helping us understand their role in the larger motor transport system, as well as their specific role in servicing rural populations.

Study Area

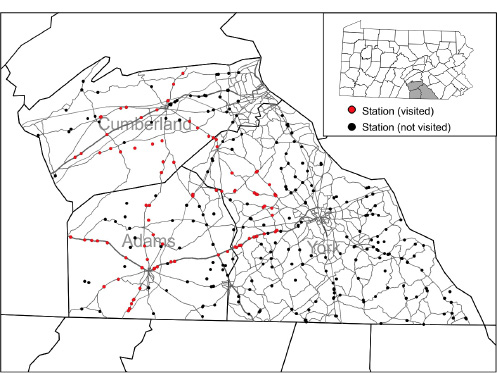

Our study area encompasses three counties (Adams, Cumberland, and York) in south-central Pennsylvania (Figure 1). The study period chosen were the decade of the 1950s and 1960s. These three counties are fairly representative of peri-urban environments found elsewhere in the mid-Atlantic region, with a mixture of well-developed urban centers transitioning to small communities and rural residences. The largest urban centers within the study area, in descending order of population are York, York county (43,718); Carlisle, Cumberland county (18,682); Mechanicsburg-Camp Hill, Cumberland county (16,869); and Hanover, York county (15,289). Adams county has no large urban centers, its largest towns being Gettysburg (7,620) and New Oxford (1,783), and Littlestown borough (4,434) (2010 U.S. Census QuickFacts).

Figure 1. South-central Pennsylvania study area. All gasoline stations (1950s-1960s) are shown.

We chose this three county region of south-central Pennsylvania as our study area because it had (and still has) a mixture of both rural and urban environments and a relatively large population. These characteristics would allow us to see the interplay between urban and rural systems with regard to gasoline service stations at a time when personal energy consumption was at its peak (Zelinsky and Sly, 1984). It was also during this period that gasoline retailing was undergoing a significant transformation, where small volume mixed-use operations were giving way to large volume single-use operations (Jakel and Sculle, 1994). Very detailed spatial data were also readily available for the area for this time period in a digital format which allowed us to put together a fairly comprehensive database of gasoline service station locations and types.

Data and Methods

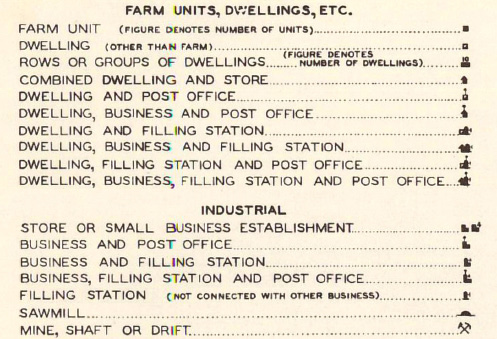

Rural service station data were derived from digital historic maps available from the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (online at http://www.dot.state.pa.us/Internet/Bureaus/pdPlanRes.nsf/ infoBPRHistoricCountyMaps) for Cumberland, Adams, and York counties in Pennsylvania (Figure 2). The maps date from the early 1940s to the middle 1960s and are very detailed as to the types of structures depicted (Figure 3). Several types of gasoline service station are depicted on these maps, along with any other building use, to form various combinations of gasoline retail (Station), residential use (Dwelling), some form of commercial/retail use (Business), and local post office (Post). So, for example, a structure could be depicted as a dwelling, business, and gasoline station or a post office, business, and gasoline station. After the maps were georeferenced, all gasoline stations were digitized by county, year, and form (e.g. business, station). Additional information on the site and situation of each station was also compiled. This information included distance to the nearest intersection, distance to the nearest town, the number of competitor gasoline station close by, and the type of road (e.g. 2 versus 4 lane).

Figure 2. A section of the 1957 York county Department of Highways map showing 5 rural gasoline stations (red arrows).

Figure 3. The legend taken from the 1953 Adams county Department of Highways map showing the level of detail in the classification of mapped structures.

Within our three county study area there were over 300 rural gasoline stations in the 1950s and over 280 in the 1960s. It was clear from the map legend that rural gasoline stations took a wide variety of physical forms, most of which were not purpose-built. To better understand these forms, we visited a random sample of 88 station locations from across the study area. These visits allowed us to compare the forms across the various types of stations, and get a better idea of their current condition.

Our first foray into our broader goal of rural gasoline stations is to describe the types of structures used and how these physical characteristics are related to the types of activities and services provided, as well as how they relate to the more general rural setting.

Gas Station Forms in the Study Area

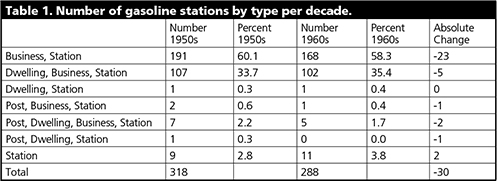

Perhaps the most important characteristic of the rural gasoline stations in our study area is that purpose-built gasoline stations during the study period were fairly uncommon, never being above 4% of the total stations (Table 1). The most common form of gasoline station were the business, station and the dwelling, business, station. Although their percentages changes slightly over the study period, these two forms of gasoline station accounted for approximately 94% of the total stations throughout the 1950s and 1960s, while purpose-built gasoline stations accounted for less than 4% of the total. An example of the business, station form can be seen in Figure 4. Keck’s Store is the only rural gas station visited that is still operating and selling gasoline. Keck’s Store’s closest competitor during the study period was over 1.5 miles distant, and no gasoline station operating then is still open. Keck’s current competitor is a newly built Sheetz station across Interstate 81 3.5 miles to the north along PA route 11.

Most of the gasoline stations that existed during the 1950s and 1960s have been removed. Of the 36 business, station locations visited that had not been removed, all tended to share a basic characteristic: gasoline sales was not the primary activity and the pumps were likely added after the construction of the building. Although the type of business was not specified on the maps, based on our survey it is likely that the most common business associated with rural gasoline stations would have been a convenience / food store. Approximately half of the business, stations found a new lease on life after they had stopped selling gasoline. Since these were often designed primarily as businesses, converting them for reuse would have been straight-forward. A typical example of business, station reuse is seen in Figure 5. This example was reused as a television repair shop, and the pump island was removed to increase parking space, although it is still clearly visible in the pavement in front of the building. However, the interior layout and shelving suggest that the building was used as some sort of convenience store at some point in its lifetime. The building is currently for sale, but it has obviously been quite some time since the last tenants moved out.

Figure 4. Keck’s store, the only operating station visited. The only gasoline pump is visible just behind the grey automobile.

Figure 5. Paul’s TV Repair, a business, station that was reused after gasoline sales ceased.

The second most common of form was the dwelling, business, station, and thirteen of this station type were visited that were not removed. This station type typically came in two basic forms: single family and multi-family. The general characteristics of this station type are that the businesses occupied the ground floor, the dwelling occupied the upper floor(s), and the gasoline pumps were a secondary function (Figure 6). In several cases it was difficult to verify if a structure had indeed been selling gasoline, since this form was often reused as a dwelling and all traces of station activity had been removed. In a few cases the outline of the former pump locations were visible in the concrete in front of the structure (Figure 7). Single family dwelling types were somewhat less common within our sample. As with the multi-family forms, the single-family forms rarely displayed any evidence that gasoline was sold (Figure 8). Often the only way to verify that gasoline had been sold was through interviews with neighbors.

Figure 6. The building on the left was a multi-family dwelling, business, and station. The upper floors housed apartments.

Figure 7. Gasoline pump impression left in the concrete in front of the building shown in Figure 6.

Figure 8. Single-family station type, currently used as storage. The remains of a pump island were barely discernable under the gravel drive.

Another common station type was the combining of gasoline sales with postal services. In all cases these two functions were accompanied by a third, or even a fourth, function. Post office and stations were combined with dwellings (single or multi-family), businesses, and occasionally both. These station forms, while easily identifiable on the maps, were very difficult to identify in the field, either because they had been removed or substantially modified through reuse. We were only able to locate and verify a single example of this station type (Figure 9). The right side of the structure with its gable-end roof was clearly added on to the hip-roof structure on the right. The garage door on the left side of the building is obviously an afterthought, since this part of the structure is simply too shallow to accommodate an automobile as the depth of the building is slightly over 8 feet (Figure 10). The post office function could be easily accommodated with an existing business or dwelling without any significant alteration of the building, and was common in rural areas. This station type, therefore, is based more on function than physical form. In no case was the post office function paired solely with gasoline sales.

Figure 9. An example of a post office, business, station that has been converted to a garage.

Figure 10. This side of the structure is too shallow to accommodate an automobile.

The final station type in the study area was that of the purpose-built gasoline station. This type displayed the least variation in physical form. Whereas the other station types took on a wide range of styles and shapes, the purpose-built gasoline station rarely strayed from the oblong box type identified by Jakle and Sculle. The house type station was also represented, but was much less common. Within the study area no shed or small box types were found (although we know of two shed type stations still standing in nearby Franklin county), and in no case did we find any of these stations with a canopy. The oblong box type structure also had a relatively high rate of reuse, especially those structures that were constructed of cinder blocks. The former Amoco station seen in Figure 11 is typical of the type found in our study area. While the layout of this type of station varied considerably, the overall design was consistent: 1 to 2 garage bays, no canopy, and a small office (e.g. Figure 12).

Figure 11. Typical oblong box purpose-built gasoline station. This former Amoco station is being used as a garage.

Figure 12. An oblong box station in Cumberland county. Subsequent widening of the road obliterated the service island.

Nearly all of the purpose built stations were reused in some manner, although none of the surveyed stations still sold gasoline. Among the surveyed stations all that were purpose built were constructed of masonry block. This substantial construction material resists decay, while the oblong box form can be easily converted to other uses. While this type of station was rare within the study area, a disproportionate number of them survive and are being reused. For example, the neglected masonry-box station seen in Figure 13 is currently used as storage for a lumber mill. The old Amoco pump is still visible (Figure 14), confirming its former use, and a particle-board addition has been added. This particular station was once along a PA Route 34, a busy highway connecting Adams and Cumberland counties in the north. At some point after the study period Route 34 was adjusted near Goodyear (Cumberland county) and this station found itself off of the main route on a less-travelled side road, which may well have contributed to its current state.

Figure 13. Another oblong box station with a wood addition. Both structures are currently being used for storage.

Figure 14. The pump of the station in Figure 13 is still in place. The sticker on the pump is for an Amoco station.

While masonry block was the dominant material used in purpose-built stations, it was not the only construction material used. Although very few remain, purpose-build stations were also constructed of wood, but decay over the years has led to few surviving, with only one example found in our survey (Figure 15). This station was well off of the main routes, and during the 1950s (when we think this station was built) this area would have been lightly populated. Today, however, exurban growth has dramatically changed this area. Rural suburban housing has become the dominant land use in the area, and this example of a wood purpose-built station has been converted into a garage for working on mid-1960s Plymouth Barracuda Fastbacks.

<

Figure 15. One of the few examples of a surviving wood purpose-built station. This example has been converted to a garage and workshop.

General Observations

Within our study area gasoline stations appear to have been much more evenly distributed in the past, and while we have no direct evidence, this was probably true of other rural areas of the country as well. What was striking about rural gasoline retailing in the region was the number of retail outlets operating during the study period. There is some suggestion that a portion (unknown) of these gasoline outlets were primarily geared towards the agricultural sector, supplying fuel for farm equipment, and that their sales to individuals for personal transport (e.g. automobiles) was limited. We feel that while this may indeed be the case, it is immaterial to our central thesis and in fact constitutes a unique form of gasoline retailing found only in rural settings. There is ample evidence in that the purchase of lower order goods, such as gasoline, is driven primarily by location (e.g. Amanor-Boadu, 2009). Consumers are more likely to purchase low order goods closer to home, which in a rural setting would result in a large number of small gasoline retailers. The diffuse nature of rural populations, therefore, resulted in an equally diffuse distribution of gasoline retailers. In a situation such as this, where each retailer served a relatively small population, gasoline sales would have been a secondary service and retailers would have adopted a strategy were additional sources of revenue would have been necessary. To meet the need in a dispersed setting, gasoline retailing would only be viable as an addition to a previously existing business or as part of a multi-use structure. This would have led to the multi-use gasoline outlet forms that we found to be so prevalent.

Additional evidence for the above processes is seen in the number of purpose-built gasoline stations observed. Very few stations in our study area were purpose-built, and those that were designed and constructed solely as gasoline stations tended to locate along high traffic routes. Gasoline-only retailers would have been at a significant disadvantage, as their service areas would have had to have been quite extensive and would have brought them into direct competition with the more advantageously situated multi-use stations.

It is our contention that, at least in rural south-central Pennsylvania, hybrid forms of gasoline retailing developed, and developed quite early. The gasoline retailing forms that Rutters, Sheetz, and Turkey Hills now typify – the multi-use form where gasoline is only a part of the larger retailing scheme – was well established and widespread by the 1950s. This form of gasoline retailer has escaped notice largely because gasoline sales were secondary, easily adopted with the addition of a fuel tank and pump, but also easily removed with little physical evidence left behind.

Perhaps the most interesting question that arises from this research is why so few of these rural gasoline retailers still exist? The processes that led to their development are still operating, so what has changed? It appears that several factors may have led to their disappearance. Changes in environmental regulations have made it much more difficult to operate a small volume gasoline retail outlet, as several of the people we interviewed noted. Consolidation of gasoline retailing may also have played a role. But perhaps the most important factor may be people’s perceptions. As automobility has matured, we have come to rely more heavily on our automobiles. We drive more often, for longer distances, and with less concern than ever before. The size of our lower-order-goods purchasing zone has increase, and we think nothing of driving farther to get groceries, clothes, and gasoline. The expectations of rural residents are falling more in line with their urban / suburban counterparts, and it has been the Rutters, Sheetz, and Turkey Hills, with their new and more modern outlets, that were poised to take advantage of these changing expectations. The older multi-use rural retailers simply removed the tanks and pumps, leaving little evidence behind of their existence.

References

Amanor-Boadu, Vincent. 2009. In search of a theory of shopping value: The case of rural consumers. Review of Agricultural Economics. 31(3): 589-603.

Pennsylvania Department of Transportation. 2005. Historic County Maps. Accessed at http://www.dot.state.pa.us/Internet/Bureaus/pdPlanRes.nsf/ infoBPRHistoricCountyMaps.html.

Jakel, John A. and Keith A. Sculle. 1994. The Gas Station in America. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. U.S. Census QuickFacts. Accessed at http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/ 42000.html.

Zelinsky Wilbur and David F. Sly. 1984. Personal gasoline consumption, population patterns, and metropolitan structure: The United States, 1960-1970. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 74(2): 257-278.

Contributor Biographies

Paul Marr is a faculty member in the Department of Geography and Earth Science at Shippensburg University in Shippensburg, Pennsylvania. His research interests are primarily concerned with landscape abandonment, and in particular the abandonment of transport infrastructure.

Claire Jantz has been a faculty member in the Geography-Earth Science Department at Shippensburg University since 2005, after completing a PhD in geography at the University of Maryland. Her research interests focus on land use, land use planning, and land use change.

Return to top