Brookwood Point: The Evolution of an Estate from Private to Public

Michele Palmer, Cornell University

Located on the western shore of Otsego Lake, in Cooperstown New York, Brookwood Point is one of the few remaining historic estates on the lake and can be considered as an example of how social changes and economic pressures have influenced an estate’s ownership and continued existence as a coherent landscape. The overall landscape of the property is significant due to its location and long history of association with prominent families of the area. A remarkable record of images and documentation, both written and oral, exist for Brookwood Point and this paper is the distillation of a Cultural Landscape Report that was prepared by the author in 2013. It will highlight the history, evolution and present challenges to preservation of the property.

The landscape design styles of the property span several time periods but fall into two broad categories: the Romantic/Picturesque and the Country Place Era. The 19th century landscape of the overall property falls into the Romantic/Picturesque tradition of Andrew Jackson Downing. The later designed landscape of the Brookwood Garden is a fine example of the Italianate style of the early 20th century Country Place Era.

Brookwood has long been seen as a special place with exceptional scenic beauty. Originally part of a several thousand acre tract, the property has gradually decreased in size to the present condition where only a small portion of the original property remains as a coherent site, with the Italianate garden particularly maintaining its integrity. A privately owned family estate from the mid-19th century, the site was placed into a trust in 1985 and was ultimately transferred to the Otsego Land Trust (OLT) in 2011.

Site History

It is unknown when the property was first called Brookwood Point, but certainly the name was in use by the mid-19th century. Brookwood Creek bisects the partially wooded land which slopes gradually towards the residence and gardens, close to the lake shore. The site contains one of the earliest houses on Otsego Lake, believed to have been built in 1832 by Cyrenus Clark, the builder of Hyde Hall.1 The property passed through the ownership of many famous local families, including Judge William Cooper, for whom Cooperstown is named, and father of writer James Fenimore Cooper and Elisha Doubleday.2 One of several local legends, it is been theorized that some of the earliest games of baseball may have been played on fields at Brookwood Point. Brookwood Creek is described by Ralph Birdsall in The Story of Cooperstown as being the stream in a scene from The Deerslayer. Cooper described a creek:

“Here Hetty performed her ablutions; then drinking of the pure mountain water, she went her way, refreshed and lighter of heart.”3

Brookwood had been a farm but when acquired in 1855 by Dr. George Maynard, a wealthy inventor, the property was transformed into a gentleman’s estate or summer retreat. The residence was altered from what was most likely a simple Greek revival house. The earliest photographs of the residence are from Maynard’s ownership in the 1860’s and contain views of the east facing facade (Figures 1-2). An additional view depicts the landscape closer to the lake (Figure 3). The images provide the only evidence available regarding the landscape and site circulation in this period, showing gravel walkways, a cast iron urn, a bench and minimal landscaping around the residence with the rustic fence to the far right which appears in the second view. The distant view portrays an open lawn with scattered mature trees and a rustic fence. These views illustrate the Picturesque design tradition, typical in the Upstate New York and the Hudson Valley, popularized by Andrew Jackson Downing.

Figure 1. East Facing Facade, Brookwood Cottage c.1860, NYSHA Archives.

Figure 2. East Facing Facade, Brookwood Cottage c.1860, NYSHA Archives.

Figure 3. View to North from Two Mile Point, 1860’s, NYSHA Archives.

Brookwood Point and the surrounding lands were purchased by Elihu Phinney in 1876, the owner of a successful publishing company. He transformed the house into an eclectic Victorian style, sometimes described as Italianate, and further enhanced the property but maintained the older picturesque landscape style. Phinney mortgaged the property to James Jermain who took control of the estate in 1880. He and later his granddaughter, Katherine Jermain Savage Townsend, proved to be the wealthiest owners of Brookwood. The family retained the property from 1880 until 1944, longer than any other owners, leaving an indelible mark on the site.

Jermain, known as a philanthropist and financier, was a one of the wealthiest residents of Albany, and perhaps the United States. Brookwood served as a summer residence for the family and under his ownership the property became a more formal estate. A photograph from the 1880’s shows minimal plantings around the residence which is set in a very open, tree and lawn landscape with a sweeping drive and tear-drop shaped drop-off loop in the older Picturesque style (Figure 4). The landscape was further enhanced with Gothic influenced details included the bridges and fencing, the house was enlarged and outbuildings such as sheds and an ice house were constructed. The known images support the account in the Freeman’s Journal describing improvements to the carriageway made by Jermain:

“Brookwood Pt. This beautiful spot, the property of Mr. James B. Jermain of Albany has lately been made still more attractive by several marked improvements. A new carriageway intersects the old one about 600 feet from the main entrance, which is widened from 11 feet to 15 feet. A common road for rough traffic has been constructed from the highway through the old Pearson lot to the cottage on the Point. The cottage itself will be enlarged by a commodious addition on the south, for servants, dining, and sleeping rooms. … this locality will be more noted than ever for its peculiar attractiveness.”4

Figure 4. West Facing Facade and Carriage Loop, Brookwood House 1880’s, NYSHA Archives.

By the turn of the century, the region had become a popular location for the summer estates of wealthy society families, especially New Yorkers. Within easy travel distance from New York City and Albany, whole families decamped to Cooperstown for the summer, a practice that continues today. These seasonal retreat properties were important and allowed families respite from city life to experience country life in a natural, lakeside setting.

The Brookwood Point property was particularly scenic and attracted several well-known artists including Edward Gay who was in the area painting the source of the Susquehanna River in the early 1880’s.5 Two of his paintings of Brookwood are located in the Fenimore Museum and feature two views, the first looking towards the Village of Cooperstown and the second, looking north with a long view of the lake. A later painting, c. 1888 by George Waters, a Hudson River School artist, renders a view from near the entry looking east towards the residence (Figure 5).6 In this painting and in a photograph taken from nearly the identical location, the landscape appeared more mature while it retained its tree and lawn Picturesque character.

Figure 5. Brookwood Estate, George W. Waters, 1888-89, McLean Gallery, Albany New York.

Upon Jermain’s death in 1897, Brookwood Point was left to his granddaughter, Katherine Jermain Savage Townsend who had married Fredrick de Peyster Townsend in 1895. Frederick and Katherine would spend summers at Brookwood with their seven children until WWI. The Townsends were responsible for creating the formal Italianate garden which includes the existing garden terraces, garden house, sculpture, and furnishings.

During this period, the original Brookwood house had further evolved into an eclectic, mostly Victorian appearance. While it is likely that the Townsends augmented the existing Picturesque landscape of the wooded estate, it appears they largely maintained the improvements installed by previous owners. Several oral histories recorded in 1974 and archived in the NYSHA library, will be referred to and describe the lifestyle of the Townsends at Brookwood.7 They entertained and hosted musical and theatrical events while enjoying a less formal lifestyle in a rustic setting that they seem to have viewed as Arcadian. Several photographs depict boating, tent camping and images of the children of the family portrayed as woodland sprites. The informant Mrs. Frederick Townsend Jr., wife of the Townsend’s oldest son, stated that Katherine kept the interior Victorian and refused to have electricity installed. Other informants described a high society life, which included servants and a cook, even as part of this less formal summer residence.8

Frederick de Peyster Townsend

Frederick de Peyster Townsend, a pre-eminent landscape architect, was both owner and designer of additions to the estate property. He was born in Medford, MA in 1871, to an affluent family, attended Williams College and studied at Harvard. He practiced full time as a landscape architect until WWI and on a limited basis after the war.

It is believed that the Townsends moved to Buffalo after their marriage in 1895 and Frederick must have received professional training in offices there. Buffalo was the eighth largest city in the United States at the turn of the century, was experiencing rapid expansion and with its prosperous economy, would have been an ideal location for a landscape architect embarking on a practice. It was also a center for culture and the arts.

It appears that Townsend went to Harvard in 1898 and 1899 to augment the training he had received from professional practice in Buffalo. At Harvard, Townsend would have been exposed to the Beaux-Arts Style that was popular at the time. For the remainder of his career, Townsend’s work would be characterized by this style. Taking inspiration from European Beaux-Arts design style, the “Country Place Era” style became popular in residential design in America.

The Country Place Era extended from approximately 1880 until 1940 and was characterized by large formally designed estates in a variety of eclectic styles, but most often in a Beaux-Arts style.

“Characteristic design features include formal garden styles, such as allées, terraces, fountains, and garden sculpture. Designers worked in close partnership with clients to create extravagant gardens inspired by European and Asian precedents in order to lend a sense of tradition, age, and affluence to what, in many cases, was ‘new money.’ Taking inspiration from European Beaux-Arts design styles, there was a return to symmetry and more formal geometries. Prominent designers included Charles Platt, Frederick Law Olmsted, and Beatrix Farrand. Instigated in part by the vast fortunes industrialization created for the wealthy, for most this era ended abruptly with the onset of the Depression.”9

After Harvard, Townsend continued to live and work in Buffalo and served on the architectural team for the Pan-American Exposition held there in 1901. He partnered with Bryant Fleming in 1904, better known for establishing the landscape architecture program at Cornell University. Townsend and Fleming established a highly successful practice from 1904 until 1915 when they dissolved for unknown reasons. The vast majority of their work was residential and they were known as some of the best landscape architects of the Country Place Era style. Townsend’s social connections with the elite of New York State would have contributed greatly to the success of the practice.

Influences

Key figures who influenced Townsend at the time included Charles Adams Platt and the writings of Edith Wharton .10 Platt in fact worked in Cooperstown and provided designs for additions to Fynmere, the residence of James Fenimore Cooper II, in 1910-1911.11 Edith Wharton was an important figure in popularizing the Italianate style in America. In her book, Italian Villas and Their Gardens,12 she argues that the style is very applicable to estates in America and advocated an adaptation of villa concepts. She believed the spirit of the great villas could be brought to estates in the United States without directly copying places in Italy. We see this in the design of the Italianate garden at Brookwood described below.

The Design of Brookwood Garden

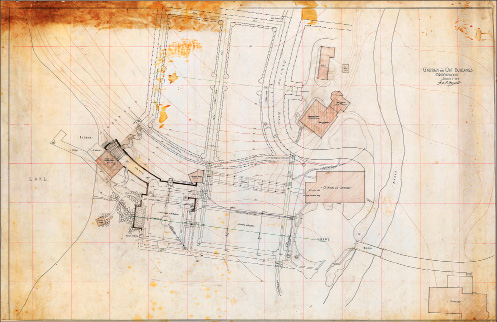

The dating of the construction of the entire garden is not exact, but clearly fell between 1915 and the early 1920’s. The Craftsman style garden house dates to 1919 so the major terracing was likely completed by this point (Figure 6). Townsend’s plan for the garden and terraces, dated 1915, is a skillfully crafted technical drawing which includes the plan layout of the garden (Figure 7). When overlaid on the site survey of 1996, it shows remarkable accuracy with what was actually constructed. The plan included descriptive labels for materials with hedges and beds shown but contained no notation of plant materials. No technical planting plans have been found.

Figure 6. Garden House photographed by Jim Kosinski, 2005, OLT Archives.

Figure 7. Pen and Ink Drawing on Linen by Frederick de Peyster Townsend, 1915, OLT Archives.

In an unusual move for a landscape architect at the time, Townsend chose to separate the new garden and terraces from the residence. Townsend’s drawing shows that he planned all of the garden and terraces on the south side of the creek as a zone apart from the rest of the site. It was typical for gardens of the Country Place Era to have a high level of integration with the house. Brookwood’s eclectic Victorian appearance may have led to the decision to keep the Italianate garden separate since it would have been difficult to incorporate into Townsend’s favored garden style with the siting of the existing house, featuring a broad flat lawn sloping down to the lake. He also may have wished to preserve the lake views from the residence as more naturalistic and drainage may have played a role as well. Since lake levels have been incrementally raised since the time of the house’s original construction, the lawn has become increasingly wet between the residence and the lake shore.

The location for the garden emphasized exceptional views to the south along the lake towards the Village of Cooperstown, reminiscent of the framed views favored in Italian villa gardens. The design consisted of a series of interconnected garden rooms with axial and cross-axial connections along with terraces in a formal Italianate style, enclosed by hedges and walls. Likely due to the existing features, Townsend created geometries which were not perfect and certain rooms were asymmetrical. However, the overall design had pleasing proportions. Figure 8 is an analysis diagram highlighting the elements of the Italianate garden and the spatial relationships within it. The garden is locally sometimes termed a ‘secret garden’ and it was clearly intended to be enclosed and separated from the rest of the property. The garden and garden house played important roles in the social life of the family with many references to garden parties, theatrical events and of the family spending a great amount of time in the garden. The garden house was also used as schoolroom on the upper level with a bathhouse below. The whimsical sculptures and decorations of the garden would have appealed to children (Figure 9).

Figure 8. Analysis Diagram Overlaid on the 1915 Plan by Frederick de Peyster Townsend, drawn by Michele Palmer and Elizabeth Kushner, 2013.

Figure 9. Fountain with Pan, photographed by Jim Kosinski, 2005, OLT Archives.

The earliest photograph of the garden terraces illustrated a “victory garden,” planted on the upper terrace with “Brookwood Garden WWI” in pen on the reverse (Figure 10). The overall garden design were incomplete but the terraces in place with vegetables growing where the lawn panel will be on the upper terrace. This would date the photograph at just after the war as the garden house was built in 1919. Since both Frederick Sr. and Jr. were in the Army, it seems likely that the vegetable garden was a patriotic statement as well as a source of food production.

Figure 10. Brookwood WWI, circa 1919, OLT Archives.

World War I clearly played a role in the evolution of the estate. The building of the garden was interrupted while Frederick was away and the couple became estranged shortly after he returned. Thus the planned design for the entire garden was never completely realized. American society was changing and upper class society life became less tenable, further breaking down during the Great Depression. After the Townsends divorced in 1924 it appears that no further implementation of the 1915 plan occurred. Katherine retained ownership of the estate and in 1927 married Edgar Chapman, an Albany Attorney. The Chapmans lived in New York City for a large part of the year after their marriage but Katherine continued to spend summers at Brookwood, apparently much in the lifestyle that she and Townsend shared. In photographs from this time period the garden appeared well tended and continued to mature into the 1930’s and 1940’s (Figure 11).

Figure 11. View of Lower Terrace c. 1940’s, OLT Archives.

Subsequent Ownership

By 1944, Katherine had apparently lost the fortune she had inherited and was forced to sell the 36 acre Brookwood property, along with other properties she owned. Katherine’s financial situation was due to the stock market crash and the subsequent Depression, but it was believed that she mismanaged her personal finances as well. Mrs. Frederick Townsend Jr. noted that her husband had expected to inherit the property, was upset at the sale and that Katherine had apparently kept her degree of financial difficulty somewhat hidden. 13 Another informant, Mr. Charles Byrnes, describes Katherine in her reduced circumstances as “brave in defeat.” He believed she sold the property to the Cook family because as owners of the local car dealership, they were outside her social circle.14 She would not have attended social events at the property which she could have found embarrassing. The result was that Brookwood was sold to an owner who, while comfortable, eventually did not have the financial resources to maintain the property.

It was clear that Katherine still had a strong attachment to the garden. When Katherine sold Brookwood Point, she retained lifetime use of the garden and garden house until her death in 1962. The new owners, “Harry” and Robert “Bob” Cook (father and son) both resided at Brookwood through 1964 when the property was conveyed to Bob Cook, making him the sole owner. The relationship between the Cooks and Katherine seemed generally cordial but letters describe differences over the maintenance of the garden.15 In a letter dated 1949 she expressed disinterest in maintaining the garden house for Bob Cook’s use. In a letter dated 1957, to Frederick Jr., Harry Cook explained the situation as one in which Katherine failed to perform any maintenance on the garden. It appears that this sort of ‘limbo’, where the Cooks owned the property but Katherine retained use, resulted in little change to the garden and may have in fact contributed to its preservation.

In the 1970’s Bob Cook took an interest in replanting the Italianate garden which had become quite overgrown, apparently planting perennials and installing small flowering trees. In the 1980’s, Cook investigated other ways to restore the garden and to develop the site as a public park. Cook never married or had children and was the last individual owner of Brookwood. He also had financial difficulties and in particular, high taxes – lake front property is taxed at a much higher rate, and maintenance on the property had become burdensome. He sold several parcels at the edges of the property reducing the estate to its current 22 acres. Cook could have easily subdivided the property further or sold it to a developer, but he, like Katherine, had great affection for the property and wished to see it preserved. He established the Cook Foundation for the Preservation and Beautification of Otsego Lake in 1985 and gifted the estate to the Foundation. Bob Cook died in 1999.

The Cook Foundation continued to maintain the garden and garden house through volunteer labor and grants. Capable gardeners have generally tried to maintain the loose planting style that would have been part of the original garden and the overall estate was essentially preserved except for minor repairs. However, the structures on the site suffered with the greenhouse and carriage house decaying to the point of collapse. The main house was poorly maintained and its future is in jeopardy. The Cook Foundation managed the estate until its donation to the current owner, the OLT, in August of 2011.

Of the once many historic estates that existed in the Cooperstown area, few exist intact. Estates with notable residences such as Glimmerglen, Fynmere, Fernleigh and others are altered or structures have been demolished so that they retain little of their historic character. The remains of the Brookwood Point estate do retain essential quality and constitutes the core area where the families who lived there focused their attentions, retaining a high integrity though spatial relationships have become difficult to read because of the deletions mentioned. Lack of funding on the part of the Cooks and the Cook Foundation may have ironically led to the preservation of the garden and the house since no major renovations ever took place that would affect the historic integrity of the site. This benign neglect condition, while saving the estate from changes in fashion and misguided renovation, has resulted in a slow deterioration that is now threatening the garden and site. The OLT, a non-profit organization, understands the legacy that they hold in trust but the costs and logistics are daunting. Its scale and condition pose substantial financial challenges since no endowment was left with the gift of the property.

Design decisions made by Townsend may be inadvertently affecting the preservation of the residence. While the garden is much beloved by the local community, the residence is seen by some as somewhat irrelevant to the garden and the cost of renovating and maintaining the residence is formidable. There is no program or tenant for the house and no means of financing the necessary repairs are available at this time. In the current situation where funding is not available at the required levels, preserving the garden is the less costly alternative and is currently, by necessity, a priority over the residence.

In encouraging news, in 2012, the OLT obtained an $188,000 Scenic Byways Grant to fund the initial costs of providing public access to the site. The OLT has successfully raised the required $62,000 matching funds though contributions from donors both large and small in what is hoped to be just the beginning of an investment in the future of Brookwood Point. The legends, the stories, the scenic beauty and the people who have been involved over the years make Brookwood Point a remarkable place and it is hoped the community will continue to support efforts to preserve this exceptional property for future generations.

Acknowledgments

I would like recognize the assistance of many members of the Cooperstown Community who contributed to the preparation of this paper including Harry Levine, Joseph Homburger, Gilbert Vincent, Connie Tedesco, Pat Thorpe and Martha Frey. In particular, C.R. Jones was kind enough to answer endless questions and e-mails. His personal knowledge of the garden, his dedication to preserving the documents related to the garden and his guided tour through the archives at the NY State Historical Association Library in Cooperstown were critical for helping us understand and interpret all of the archival materials available in many different locations. Prof. Daniel Krall also kindly acted as reader.

Endnotes

1 Begun in 1817, Hyde Hall, was built by George Clarke (1768-1835). Now a National Register property, the house is considered one of the finest examples of the neoclassical country house in the United States.

2 The original abstract of title is held the Otsego Land Trust archives. It appears to have been prepared for Mrs. Katherine Jermain Savage Townsend around the time she inherited Brookwood from her grandfather James B. Jermain in 1897. It was prepared by her attorney and describes all of the changes in the title to Brookwood, beginning with Croghan’s acquisition from local Native Americans as part of a patent that included thousands of acres of land in the 1760’s. Elisha Doubleday is believed to have been a cousin of Abner Doubleday, reported founder of the game of baseball.

3 Cooper, James Fenimore. The Deerslayer; or, The First War-Path. A Tale by J. Fenimore Cooper. New York: Stringer and Townsend. 1854.

4 The Freeman’s Journal, November 11, 1882.

5 Gay, Edward B. Otsego Lake Looking South and North from Two Mile Point, 1882, located in the Fenimore Art Museum.

6 Waters, George W. Brookwood Estate, 1888-89, painting owned by the McLean Gallery, Albany New York.

7 Laskovski, Patricia and Mathes, Wayne. “The Brookwood Farmstead.” New York State Historical Association (NYSHA) Library, archived interviews, 1974.

8 Laskovski, and Mathes.

9 The Cultural Landscape Foundation http://tclf.org/content/country-place-era-garden

10 Knight, Gayle Sanders. Bryant Fleming, Landscape Architect: Residential Designs 1905-1935. Thesis (M.A.) Cornell University, 1987.

11 NYSHA Library, Cooperstown, New York. Fynmere estate plans, 1881-1961 (bulk 1911-1916). Maps and blueprints of Fynmere, the estate built by James Fenimore Cooper, II, on Estli Avenue, Cooperstown, N.Y., from 1911 to 1916. Includes sketches by Frank Whiting and revisions by Charles Platt, both architects. Also contains landscape architectural plans by Ellen Shipman.

12 Wharton, Edith, Maxfield Parrish, E. Denison, Malcolm Fraser, Charles A. Vanderhoof, and Deborah Pease. Italian Villas and their Gardens. NY: Century, 1904. Pp. 5-13.

13 Laskovski, and Mathes.

14 Laskovski, and Mathes.

15 Letters held in the Otsego Land Trust Archives.

References

Bennitt, Mark. The Pan-American Exposition and How to See It. Buffalo: The Goff Company, 1901.

Birdsall, Ralph. The Story of Cooperstown. Cooperstown, N.Y.: Arthur H. Crist. 1925.

Chapman, E. T. Attorney at Law. Cook/Katherine Jermain Chapman Rental Agreement. Otsego Land Trust Archives. Cooperstown, NY, 1944.

Clothier, S. J. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form - Brookwood Garden House. Cooperstown, NY, 2000.

Cooper, James Fenimore. The Deerslayer; or, The First War-Path. A Tale by J. Fenimore Cooper. New York: Stringer and Townsend, 1854.

Dolan , Susan A. , Gilbert, Cathy A. , Page, Robert R. A Guide to Cultural Landscape Reports: Contents, Process, and Techniques. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1998.

Duchscherer, P. Outside the Bungalow - America’s Arts and Crafts Garden. New York: Penguin Putnam, Inc., 1999

Edison, Thomas A. Film of the Opening of the Pan-American Exposition. Thomas A. Edison, Inc., 1901. Library of Congress ID # lcmp001 m1a06210, Photographed May 20, 1901. Location: Buffalo, NY. Can be viewed on YouTube at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ziqatEeoZnc

The Freeman’s Journal. 1819. Cooperstown, Otsego County, N.Y.: J.H. Prentiss.

Gratwick, William. My, This Must Have Been A Beautiful Place When It Was Kept Up. New York: Pavilion, self-published, 1965.

Knight, Gayle Sanders. Bryant Fleming, Landscape Architect: Residential Designs 1905-1935. Thesis (M.A.) – Cornell University, 1987.

Laskovski, Patricia and Mathes, Wayne. The Brookwood Farmstead. Cooperstown: Paper for the Cooperstown Graduate Program. 1974. Copy held in New York State Historical Association Library, Cooperstown, NY,

Little, Walter. A History of Cooperstown. Cooperstown: Freeman’s Journal Co., 1929.

Newton, N. T. Design on the Land: The Development of Landscape Architecture. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971.

New York State Historical Association Archives – Cooperstown, NY, Deeds, Letters and Photographs related to Brookwood. Fynmere estate plans, 1881-1961 (bulk 1911-1916). Maps and blueprints of Fynmere, the estate built by James Fenimore Cooper, II, on Estli Avenue, Cooperstown, N.Y., from 1911 to 1916. Includes sketches by Frank Whiting and revisions by Charles Platt, both architects. Also contains landscape architectural plans by Ellen Shipman. James Fenimore Cooper, II, was the grandson of novelist James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851).

Simo, Melanie L, and Anthony Alofsin. The Coalescing of Different Forces and Ideas: A History of Landscape Architecture at Harvard, 1900-1999. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 60 (1): 96, 2001.

US Department of the Interior and National Parks Service. National Register Bulleting 15: How to Apply the National Register Criteria for Evaluation. Date of publication: 1990; revised 1991, 1995, 1997. Revised for Internet 1995.

Wharton, Edith, Maxfield Parrish, E. Denison, Malcolm Fraser, Charles A. Vanderhoof, and Deborah Pease. Italian Villas and their Gardens. New York: Century, 1904.

Contributor Biography

Michele Palmer is a licensed Landscape Architect and Lecturer in the Department of Landscape Architecture at Cornell University, where she has taught site engineering and design courses since 2002. She holds the Master of Landscape Architecture degree from Cornell and a B.A. in the History of Art from Colgate University. Research interests include the cultural landscape, landscape archaeology and the history of site engineering. Michele can be contacted at map20@cornell.edu.

Return to top