Staple Anew: The Potential of an Adaptively Re-Used Gasoline Station in Powell, Wyoming

Keith A. Sculle, Illinois Historic Preservation Agency

Adapt a gasoline station for a community arts center? Just the sight of the incongruous turn about in Powell, Wyoming, a small town (6,314 in 2010), raises questions in this author’s mind of why it was done, who did it, and what potential, if any, might it have as a general future practice in towns and cities of any size. Service to a community’s artistic sensibilities seems such an unlikely re-use for a building born of commercial interests and trademark, not artistic design. Its intended public benefit, however, overcame the usual opposition to disclose the plans behind the facade which private owners maintain. Public managers in Powell were glad to make their plans public.

Introduction

Gasoline stations were long known in the United States as service stations, the adjective “service” referring to the work of the attendant who checked oil levels and filled gasoline tanks for customers’ cars. These stations came of age in the twentieth century with mass automotive transportation. Although seldom revered for their architecture and, in fact, often denigrated as low quality sheds with shabby utilitarian surroundings, they also resonated as proof of a town’s viable economy. Neither like a palatial hotel catering to their town’s social life nor, in an earlier time, like a railroad depot proving connectivity to the world beyond, gasoline stations were nonetheless secure fixtures imbedded in every growing town’s street grid. Uncelebrated but surely mundane symbols of the good life taken for granted: that was the twentieth century gasoline station.

Today, thousands of gasoline stations stand idle, their underground tanks awaiting removal to secure healthy environmental standards in keeping with new understandings for the good life. The convenience store inside selling small personal items, newspapers, and simple foods and drinks, and outside offering self-service gasoline has replaced the service station, moved by expedience to entitle itself “full service”. Should this new version, the convenience store with minimal automobile service be singled out for discussion, it is infrequent and reduced to uncomplimentary characterization as just another contributor to roadside sprawl. Now a remnant of another age, the old service station yet can survive in an architectural shell adapted to contemporary service refitted for environmental responsibility, and be embraced as an asset serving a vibrant community.

Studies of the automobile’s adoption and development have given comparatively little place to the utilitarian elements enabling it, except for the history of highways and interstates. Such as the gasoline station are usually viewed from the perspective of the origins of their trend-setting architecture and spatial influences (Longstreth 1999; Vieyra 1979). The few innovators of an expanded perspective include Annmarie Adams for her admirable study of how a photographer “implicates the individual gas station in a larger network of human activity” and Jim Draeger’s and Mark Speltz’s inclusion in one state of some stations whose newest different uses are a worthy part of each building’s history (2005, 38; 2008).

During the first quarter of the twentieth century, a very sophisticated and specialized architecture emerged to sell gasoline for what had begun in the 1910s as a heterogeneous collection of outlets for various consumer goods and services. Grocery stores, hardware stores, automobile repair and storage garages, even livery stables, added gasoline sales, wherever it fit, into their primary inventory. Gasoline pumps were the primary visual cue of availability to drivers of automotive vehicles in search of fuel. Pumps avoided the impurities of open containers and reduced evaporation of supplies in waiting. A specialized building whose pumps were available for use beside the street curb or in a drive-in mode offered greater commercial opportunity. Petroleum companies appreciative of the growing demand for automotive fuel also began in the 1910s to adopt trademarks, brand names, advertising slogans, and stations that looked alike in building design and layout on site. Their emergence symbolized the attractiveness of the new automotive petroleum technology; where gasoline stations sprang up, it could be inferred that the community was growing, was vital in adopting new ways. Uncelebrated but surely mundane symbols of the good life taken for granted: that was the twentieth century gasoline station. They signaled a coming of the automotive age. But, they were not necessarily visual assets. Corporate architecture grew with the functional accouterments of trademarks and such. It quelled widespread complaints about garish settings cobbled together and often fit into residential neighborhoods where stores had seemed fit but never originated in service to smoky and noisy automotive machines.

To adapt gasoline service in small towns, stations were built in a vernacular style like local houses (Sculle 1981). Big corporations with eyes upon big urban markets fashioned stations attractive to a market based in neighborhoods built in period-style architecture. Pure Oil Company and Phillips Petroleum Company first conceived and implemented this strategy for private profit in the late-1920s (Jakle and Sculle 1994, 163-182). Although corporate chains of stations were exercised in different ways to fit in big or little community-based markets, they shared the same commitment to private profit. Thoughtfully adopted at first as symbols of a community’s far sightedness and, by mid-century, assumed without residents’ regular assessments of their appropriateness, petroleum corporations carefully calculated their gasoline stations private profit and loss.

As the fortunes of technological changes often have it in a capitalistic economy and given the constantly disapproving murmur about automobility (Ladd 2008), however, gasoline stations became something of social as well as economic liabilities. They have become a bellwether for the economic fortunes of the places in which they were situated.1 By the late-twentieth century, decreasing demands for petroleum and rising environmental complaints about fossil fuels witnessed a significant decrease in the number of gasoline stations as well as their reputation for social service in the late-twentieth century. Between 1994 and 2012, their numbers declined from 202,878 to 159,141 (How Many Gas Stations Are There in the United States, 2012) and legal demands were laid down to remove the fuel tanks from the unoccupied stations (Recycling America’s Gas Stations 2002, 9).

Those extant gasoline stations presented opportunities. The major voice rose from historic preservationists who naturally encouraged re-use but that any adaptations be made consistent with original building designs (Randl 2006). The unorchestrated examples of the greater number of users, the private shop owners who acquired the unoccupied stations, simply addressed the question of how best to use the buildings regardless of alterations by what they did. A few of the idle buildings have been turned to public use and rarely both public and private use drawing on historical associations.2 Unfortunately, this author has learned that commercial owners of existing examples are reluctant to share much about their place of business. Private property may have public implications but the secrets of success and operation regardless of success are carefully guarded. Their buildings are left to speak for themselves through drive-by interpreters, a subject for attention elsewhere. Powell, Wyoming’s community arts center brings attention to the work making it because it is such a well documented example whose history unto the very present is gladly shared by those with interests beyond private enterprise. The potential of adaptively re-used gasoline stations can be appreciated here in depth.

Case studies are the irreplaceable data on which reliable generalizations depend. Individuals do not act within general trends as if teleological agents. One of the founders of automobile studies wrote in his career-concluding monograph of 1988, after 28 years of research and writing: “history is the product of human choice, made by decisions of men

rather than the inevitable result of impersonal forces, cultural or otherwise, . . .” Hence, “due attention is given to the contributions of individuals to the shaping of our car culture, . . . .” (Flink 1988, ix). A revisionist recently pointed out the need to understand the automobile within changes made since that landmark study of 1988 (Heitmann, 2009, 2). Committed to the belief in the free will of human agency, individuals as the force of historical trends, the gasoline station as a sine qua non of automotive culture, and the need to update scholarship, this case study is offered for a small contribution to what should become a growing field of knowledge about the adaptive re-use of one of the American car culture’s leading but proportionately less chronicled enablers (Sculle 2012).

Plaza Diane’s History

Powell, Wyoming stands out for its remarkable achievements in the state’s extreme northwest corner where Cody generally garners the area’s urban attention as the gateway to the prestigious Yellowstone National Park. Theodore Roosevelt coined the phrase “the most scenic fifty miles in the world” for the road between Cody and the park and by the end of the twentieth century the road entered the select ranks of the National Scenic Byways Program. Twenty-four miles east and founded a few years after its illustrious neighbor, remarkable accomplishments, in fact, have long earmarked Powell’s historical emergence from the seemingly unpromising sagebrush surroundings. Since mid-twentieth century, the economy grew considerably due to the discovery of a nearby oil reservoir, the World War II-boom in agricultural production, construction of an internment camp for Japanese-Americans, and the University of Wyoming’s Northwest Center founding in 1956 (later Northwest Community College) (Koelling 1997, 75). This rally stunningly contrasted with the previous twenty years of agricultural depression which the following global depression had worsened. Shortly before his death in the 1930s, Powell’s leading banker lamented in a handwritten biography his “outstanding error of judgement being that of locating in this thinly-settled western country” (Koelling 1997, 55). Powell’s people, of course, were at the root of the city’s remarkable resilience. Many of its founders’ intelligence and industriousness were considered above the average for rural areas (Koelling 1997, 23). Its eighty-foot wide streets and 100-foot main street convinced outside observers, as similarly expansive dimensions when other western towns were founded, that ambitions were equally expansive (Koelling 1997, 21). When the Presbyterian church founded a retirement home in Powell in 1965, the economic diversification was welcomed (Koelling 1997, 84). Thoughts turned to downtown renovation in the early 1960s although the project stalled because business owners opposed its formulation as a pedestrian mall (Koelling 1997, 89; Bonner and Churchill 2008, 198). Powell’s leading bank offered economic development initiatives in the 1980s, encouraged area banks to get involved, Powell was designated an All-American City in 1994, and Wyoming’s Governor and Secretary of State declared Powell’s work a model for the entire state (Koelling 1997, 99).

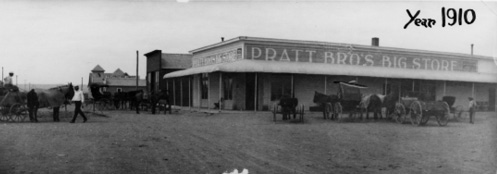

Figure 1. In 1910, the location on the right side of the image that Plaza Diane would occupy a century later. Courtesy of Homesteader Museum, Powell, Wyoming.

It was this entrepreneurial soil (Figure 1) and persistently community-minded geist that made feasible the Plaza Diane, originally a gasoline station but converted to a civic arts center representing Powell’s centennial (Community Center for the Arts, June 27, 2013). The completed explanation for Plaza Diane hinges on following the trail of the groups and individuals who brought off the final accomplishment. Plaza Diane would not exemplify an unchallenged ideological triumph. Powell experienced the preference for sprawl rather than downtown renewal, as did many cities and towns in the age of automotive vehicle popularity. It would have made improbable a civic accomplishment like a reused gas station in the old city center. On Powell’s west side in 1980 talk bloomed of building a shopping center and, in the following year, one on the east side, but both failed due not to overwhelming disapproval but sufficient concern that downtown commerce would suffer more. There the sixty-three year old Chevrolet-Buick auto dealership, the Chrysler auto dealership, Montgomery Ward, a member of a national supermarket chain, a half-century old dime store, and two hardware stores were shuttered, all in the early 1980s (Bonner and Churchill 2008, 242). The 1990s contrasted with this downward trend; for the early part of the decade witnessed the city chamber of commerce’s downtown revitalization. An outside consultant (from Colorado), Mariann Novak, hired by Wyoming’s Division of Community and Economic Development, worked to persuade downtown leaders that downtown investment would earn profits. Although they were not uniformly convinced, the downtown steering committee produced a $2.8 million design to achieve success and the local newspaper studiously promoted the solutions. Opponents numbered 40 percent of the business owners in the improvement district but, even with required funding reduced to $1.5 million, it still fell short of $70,000 private donations for completion. New sidewalks, curb, gutter, electrical, and water lines were finished in 1994 and the new lighting and trees at 50-foot intervals symbolized a renaissance (Bonner and Churchill 2008, 271-72). Government, business, and the schools included the downtown revitalization with several other projects in Powell in submitting their city’s name to the National Civic League contest for an All-American City and Powell was one of the winners in 1994 (Bonner and Churchill 2008, 272-73). Three years later, The Commons, a multi-purpose activity center downtown, was opened. It had originated as an auto repair garage in the 1920s, and when it closed the front of the building was redeveloped as a pocket park. The city of Powell eventually purchased the property (Bonner 2009, 31).

Figure 2. The gasoline station later adapted for Plaza Diane. Courtesy of

Homesteader Museum, Powell, Wyoming.

Enter the specifics of Plaza Diane. An ENCO gas station built in 1945 (Figure 2), a Community Development Block Grant to remove slum and blight funded remodeling it for a private business (Community Facilities Grant and Loan Program Report, 2008, 14). Thus, in 2001, a stage canopy was built, the building’s interior was gutted and remodeled, and – with an auspicious declaration of intent – was named the Plaza Diane (Figure 3) for Diane Bonner. In the long-tradition of community minded women in Powell, Bonner stood for many civic projects, wrote for the local newspaper, and was a city councilwoman, before she died in 2000. However, too cold in the winter and its exterior too hot in the summer (due to reflected sunlight off the concrete pavement), the building remained vacant during most of 2001, the city having failed in several attempts to win occupants (Bonner 2009, 31). Powell began using the site for outdoor concerts (Community Facilities Grant and Loan Program Report and Recommendations to the WBC Board of Directors, 2008, 14). By 2007, the city was no longer willing to pay taxes and maintenance on the building, turned to the prospect of selling the building to a private owner, but a group of about thirty people proposed a plan to convert the old gas station into a community center, as a journalist for the local press wrote, complete “with gardens, gallery space, and, most important for many, shade” (Bonner 2009, 31).

Figure 3. Architect’s view (looking west) of anticipated Plaza Diane. Courtesy of Toby Bonner, Powell Tribune.

In mid-May the following year, at two public meetings of the Plaza Diane Steering Committee, no one spoke in opposition and $944,012 was requested of the Wyoming Business Council for a Community Facilities Grant, nearly $190,000 anticipated from local contributors or roughly 15 percent according to state requirements (Bonner 2009, 31). The grant was given, Plaza Diane volunteers worked with the city, CTA architects, principally Anya Fiechti, from Billings, Montana, created the design, and Sletten Construction in nearby Cody completed the work. Work for these two area businesses won the project further acclaim. It was designed to be both environmentally friendly and, to be useful to the community for art shows, classes, meetings, and other local events, housed a splash pad for children, shade sails, moveable walls indoors to maximize versatility, and 220 square feet added outside for a public restroom and storage (Schweigert 2009, 1 and 3; Community Facilities Grant and Loan Program Report, 2008, 14). Numerous but not insurmountable difficulties emerged. It was a small space with pre-existing utilities and infrastructure (Schweigert, 2009, 3). Petroleum had saturated soil on site but it was determined safe to remove to a landfill. Before scheduled completion, problems arose including the wrong kind of gallery lighting and an inoperable splash pad – to the children’s dissatisfaction – after the first winter (Investment Ready Communities 2010, [pp. 4-5, and 7]).

Withal, Powell realized broad benefits. Beautification of the run-down station with new indoor opportunities achieved the aim of drawing people downtown for community activities with the residual benefit of more customers for downtown businesses (Investment Ready Communities 2010, [p. 2]). There followed enhanced quality of life, downtown rejuvenation, and faith that families and businesses would invest in Powell (Investment Ready Communities 2010, [p. 2]). On opening day, August 27, 2009, Mayor Scott Mangold pronounced: “Our history is right here, at this location.” Diane Bonner, for whom it was named, “knew this and wanted to keep it going” (Mathers 2009, 8).

Programming encompassed a not-for-profit organization to operate Plaza Diane with supplementary funds, as needed, from the City of Powell. The local school district and Northwest College were to provide art programming, especially for the young. Adult art shows, outdoor movies, meeting space, and a new location of the city’s Farmer’s Market on Saturday mornings comprised the original plans (Community Facilities Grant and Loan Program Report and Recommendations to the WBC Board of Directors 2008, 15-16.)

At the time of this writing (Figure 4), the project still looked forward to add a part-time coordinator, a tie with local businesses to promote the plaza, and grants for expanded programming to appeal to new audiences. Unfortunately, there was no proof that the operation either retained businesses or attracted new ones to Powell (Community Facilities Grant and Loan Program, Annual Report 2012).

Figure 4. Plaza Diane looking northeast, 2013. Author’s photograph.

Conclusions

Originating as private business enterprises, gasoline stations have from their inception at the start of the twentieth century also had important but mixed implications for the public life of the town where they located. The ENCO gasoline station at a key intersection in downtown Powell, Wyoming, whose shell of a building and wrap-around driveway were converted to Plaza Diane at the start of the twenty-first century for community life, education, and the arts testifies to a new public conception. This remarkable case deserves on-going attention in order to contribute to the larger study of public and private meanings through the auspices of adaptively re-used gasoline stations.

An adaptively re-used gasoline station stimulates thought of many potentials. Gasoline stations long languished among scholars as subjects appropriate for study, not only architectural students but landscape geographers. Now, even their adaptive re-use, not to mention their original conception, raises questions about their social potential as another expression of commonplace culture as vernacular architecture once did. Individuals stand out as agents of change, if not heroes certainly as the means by which further considerations about change can be traced. Examples of adaptively re-used gas stations strongly suggest that buildings with public use stand more likelihood of being understood from conception and, hopefully, will survive longer than those subject to changing commercial circumstances. Adaptive re-use is tied to saving energy needed in a future world wherein resources are believed more precious than they were in the early automotive era when great growth for the marketplace was the measure of success. Certainly, they reinforce the scholarly understanding that any building can be rendered meaningful, however apparently modest. Plaza Diane is not the only gasoline station reborn in public life that will deserve attention as scholarly hypothesis itself grows with numerous studied examples. More field work will yield other deserving cases. The author’s initial amazement upon first sight of Plaza Diane, reasserts that looking at the landscape can raise essential questions that archival documentation can only assist in answering.

Acknowledgements

Rowene Weems, Homesteader Museum, Powell, Wyoming; Toby Bonner, Powell Tribune; and Shelby Wetzel, Plaza Diane Board of Directors.

References

Adams, Annmarie. 2005. Picturing Vernacular Architecture: Thaddeus Holownia’s Photographs of Irving Gas Stations. Material Culture Review 61(Spring): 36-42.

Bonner, Yancy. 2009, “Garage, gas station evolve”. Powell Tribune Centennial Edition, June 25: 31.

Bonner, Robert and Beryl Churchill. 2008. Powell’s First Century: Home in the Valley. Cody, Wyoming: WordsWorth.

Community Center for the Arts. About Plaza Diane, Powell, Wyoming. <www.plazadiane.org> (Last accessed June 27, 2013).

Community Facilities Grant and Loan Program Report and Recommendations to the WBC Board of Directors. 2008, Sept. 11.

Community Facilities Grant and Loan Program, Annual Report. 2012, May 1.

Draeger, Jim and Mark Speltz. 2008. Fill’er Up: The Glory Days of Wisconsin Gas Stations. Madison, Wisconsin: Wisconsin Historical Society Press.

Flink, James J. 1988. The Automobile Age. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Heitmann, John. 2009. The Automobile and American Life. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company.

“How Many Gas Stations Are There in the United States.” April 20, 2012, posted. National Petroleum News Survey <www.howmanyarethere.org/how-many-gas-stations-are-there> (Last accessed June 6, 2014).

Investment Ready Communities, Community Facilities Grant & Loan Program, Final Infrastructure Report. 2010, December 31.

Jakle, John A. and Keith A. Sculle. 1994. The Gas Station in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Koelling, Robert. 1997. First National Bank of Powell: The History of a Bank, a Community, and a Family. Powell, Wyoming: First National Bank of Powell.

Ladd, Brian. 2008. Autophobia: Love and Hate in the Automotive Age. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Longstreth, Richard. 1999. The Drive-In, The Supermarket, and the Transformation of Commercial Space in Los Angeles, 1914-1941. Cambridge: MIT Press.

MacPherson, Bradley D. and Mark De Socio. 2013. Gasoline Station Morphology on Virginia’s Eastern Shore. Southeastern Geographer. 53 (1): 5-27.

Mathers, Gib. 2009. Community celebrates Plaza Diane’s opening. Powell Tribune. September 1: 8.

Randl, Chad. 2006. Preservation Briefs 46: The Preservation and Reuse of Historic Gas Stations. Washington, D. C.: U. S. Government Printing Office.

Recycling America’s Gas Stations: The Value and Promise of Revitalizing Petroleum Contaminated Properties. 2002. n. p.: Report by the Northeast-Midwest Institute and the National Association of Local Government Environmental Professionals.

Schweigert, Tessa. 2009. Plaza Diane Construction Begins. Powell Tribune. March 3: 1 and 3.

Sculle, Keith A. 1981. The Vernacular Gasoline Station: Examples from Illinois and Wisconsin. Journal of Cultural Geography. 1 (2): 56-74.

_______. 2012. A Work in Progress on the Basic Gasoline Station. PAST:APAL 35 www.pioneeramerica.org/previousissuespast.html.

Vieyra, Daniel I. 1979. An Architectural History of America’s Gas Stations. New York: Collier Macmillan Publishers.

Notes

1 Regarding Virginia’s Eastern Shore, see: Bradley D. MacPherson and Mark DeSocio, 2013.

2 Consider examples in Decatur, Illinois ; Glouster, Virginia and Springfield, Illinois: in Glouster, Virginia: Dave Brown personal correspondence to Keith A. Sculle about Edge Hill Service Station, October 6, 2012; in Decatur, Illinois: Landmarks Illinois Preservation Awards 2012 <www.landmarks.org/awards_2012_texaco_station_decatur.htm> (accessed Nov. 16, 2013); in Springfield, Illinois, Keith A. Sculle, “Social Memory and the Power of Adaptive Re-use,” PAST 36 (2013).

Contributor Biography

Keith A. Sculle, Ph. D., has concentrated especially on the development and meanings of the American roadside landscape and its contributing buildings for over 40 years. He is the retired Head of Research and Education, Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, Springfield, Illinois. ksculle@gmail.com

Return to top