The Rousculp Barn: Situating a Pennsylvania Bank Barn in Time and Space

Timothy Anderson, Associate Professor, Department of Geography, Ohio University

Introduction

The structural analysis of barns, as fundamental components of North American rural cultural landscapes, enjoys a long and storied tradition in American cultural and historical geography and allied fields. Many early studies sought to develop typologies relating to form, plan and construction method and to identity and map the geographical distribution of such landscape elements, viewing material culture as “cultural spoor” that might help to delimit culture regions and uncover such phenomena as past migration patterns (Zelinsky 1958; Kniffen 1965; Glassie 1968; Hart 1968; Noble 1977; Pillsbury 1977). Such studies were firmly anchored in the Sauerian tradition and its empirical focus on material culture, folk construction techniques and rural landscapes. They should also be contextualized as examples of scholarship associated with a broader focus on what can generally be identified as an American variety of “settlement geography,” at the time concentrated on the detailed analysis of the “built environment” in order to assess settlement patterns and processes (Stone 1965; Jordan 1966). More recent barn studies employed the typologies and patterns identified by this earlier generation of scholars in analyses that address larger-scale questions and issues at the regional, national and even international scales, asking more profound questions of barns in order to assess what they can tell us about national-scale patterns and processes. Such scholarship includes highly detailed investigations of the origin and distribution of particular barn types (Noble and Seymour 1982; Ensminger 1992; Jordan-Bychkov 1988), meticulous studies of regional barn styles (Hubka 1984; Glass 1986; Comeaux 1989; Raitz 1995) and regional complexes (Kilpinen 1994; Noble and Wilhelm 1995), newer commentaries on classification and typology (Hart 1994), and in-depth analyses of individual barns or barn complexes in distinctive locales (Roberts 1993; Sculle and Price 1993; Morrison 2001).

This paper follows in the footsteps of such research through a largely empirical analysis of an extant double-crib, log bank barn in Perry County, Ohio. Such barns are relatively rare in the North American cultural landscape today, but this particular barn has endured for well over 150 years through the preservation efforts of a succession of property owners. Space limitations preclude a detailed analysis of the various social discourses “materialized” in this particular landscape element (Schein 1997, 664), but the fact that this barn has survived for so long says much about the nostalgic power that such structures possess and convey. The paper first briefly describes the barn’s architectural features and properties are defined and discussed within the context of barn form and typology. Next, its geographical setting and history is discussed. Finally, the barn is situated in time and space through an assessment of historical patterns of migration and settlement in Ohio.

Architectural Features

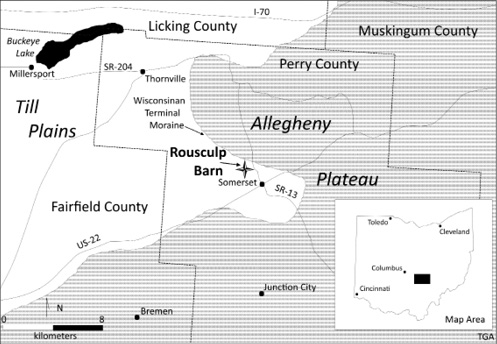

The Rousculp barn is located off State Route 757, approximately 1.5 miles northwest of the village of Somerset in northern Perry County (Figure 1). With regard to typology, the structure is a rather textbook example of a log “Sweitzer” barn (Figure 2), distinguished by a front roof slope that is longer than the rear due to the roof continuing unbroken over the cantilevered, unsupported forebay, producing the form’s characteristic gable-end silhouette. According to Dornbusch and Heyl (1958, 79-80), the Sweitzer was the earliest form of the Pennsylvania forebay bank barn to appear in colonial America, most examples of which were constructed between 1730 and 1850. In his classic study of the origin and distribution of the Pennsylvania barn, Robert Ensminger (1992, 56) classifies the log Sweitzer as a separate subtype, distinguishing it from later “classic” and “transitional” forms, and maintains that it was “… Pennsylvania’s first forebay bank barn … [representing] a direct connection to its Swiss prototypes in Prätigau” (57). Log Sweitzer barns appeared in southeastern Pennsylvania as early as 1730 and extant examples can today be encountered as far south as the middle Shenandoah Valley, as far north as southwestern Ontario, and as far west as central Ohio. Even so, the log Sweitzer was and is a rather rare form of the Pennsylvania barn, especially outside of the southeastern Pennsylvania “core” area where forebay bank barns are common. Indeed, in his qualitative study of barn forms in Ohio, Noble (1977, 68-71) found that Sweitzer barns accounted for only about three percent of Ohio’s barns; it is altogether likely that the Rousculp barn is the sole log Sweitzer remaining in Ohio today.

Figure 1. Rousculp Barn Setting. Map by Author.

Figure 2. View of the Rousculp Barn from the Front. Photo by Author.

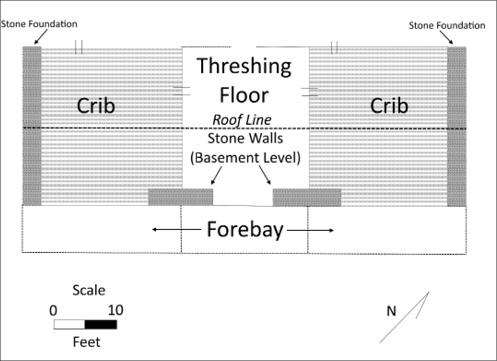

Figure 3. Rousculp Barn Floor Plan. Sketch by Author.

With regard to floor plan (Figure 3) and construction details, the barn exhibits many of the same features found on early examples of log Sweitzer barns in Pennsylvania as described by Ensminger (1992, 57-60). It is rather small (about 70 X 30 feet) compared with most other types of Pennsylvania bank barns; the entire structure is comprised of two large log cribs, separated by a central threshing floor, resting on stone basement walls (Figure 4). The framed forebay is supported by heavy log beams that cantilever under the cribs and are anchored into the rear wall of the barn. The cribs themselves are constructed from squared logs joined at the corners by V-notching and likely functioned as both hay mows and corn cribs (Figure 5). With the exception of the rear wall, the entire exterior is covered with vertically-set boards of sawn lumber. The barn originally had a slate tile roof, pieces of which still litter the site, but was later replaced with tin. The Rousculp barn is in fact mentioned briefly, along with two accompanying photographs, in Ensminger’s seminal monograph (1992, 155) as a classic example of a log Sweitzer barn. Here, Ensminger provides a construction date of 1837 but does not cite the source of this information. When asked about this at a much later date, Ensminger was unable to recall how he determined the 1837 date (Ensminger 2008). A date of 1896, together with the initials AWR, is carved into one of the barn’s stone foundation blocks, but the barn’s construction most certainly predates this, and it is altogether likely that it was built sometime in the late 1830s.

Figure 4. Side and Rear View of the Rousculp Barn. Photo by Author.

Figure 5. Barn Interior, Illustrating Log Crib and Notching Technique. Photo by Author.

Geographical Setting and History

According to Bureau of Land Management General Land Office records, the quarter section in Reading Township on which the barn is located was originally purchased by cash entry from the federal government by Christian Deal on November 20, 1812 (Deal Patent, 1812). Deal (likely originally spelled Diehl) was born in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania in 1760 and died in 1814 in Perry County, just two years after purchasing the land. His father, Christian Sr., was born in Baden-Württemberg, later immigrated to Pennsylvania, and died in Centre County in 1805. The land was still in the Deal family as late as 1828 when Christian’s widow, Susanna Deal, appeared on a Perry County property tax list as the proprietor of 315 acres — the original quarter plus much of an adjoining quarter — in Reading Township (Perry County Tax Duplicate, 1828). The Deal’s must have subsequently sold their land sometime after this date because an 1846 Perry County plat map reveals that the Deal’s half section was now owned by Nicholas Gangloff (Plat Map of Perry County, 1846). According to the 1850 federal census, Gangloff was born in Germany in 1777 and lived with his wife Appolonia and sons Jacob and Nicholas Jr., all of whom were also listed as being born in Germany. Jacob’s wife, Ellen, and their six children were also listed as members of the household (US Census, 1850). The census reveals that Jacob and Ellen’s eldest child, Angelin, was born in Ohio and was 16 years old in 1850, so the Gangloff family must have moved to Perry County by 1834 at the latest. If Robert Ensminger is correct in asserting that the barn was built in 1837, then it is likely that the Gangloff family was responsible for its construction. If, however, the barn was built earlier than this then it is likely that Christian Deal or one of his children built it sometime between 1812 and 1828.

Although the 1850 census gives Germany as the place of birth for the Gangloff’s, genealogical information compiled by family members reveals that Nicholas, Appolonia, Jacob and Nicholas Jr. were all born in the Alsace-Lorraine region of what is now northeastern France, a cultural shatterbelt region containing large numbers of ethnic Germans and a significant source region of Pennsylvania-German immigrants (Gangloff/Wahl Family Group Sheet). Most Pennsylvania-Germans immigrated to Pennsylvania in the 18th century, but according to immigration records the Gangloff’s arrived in 1829 (US Index to Passenger Arrivals). They must have moved to Ohio sometime during the next decade, as they appear in the 1840 census of Perry County. Sometime shortly after 1850 the Gangloff’s moved on: Nicholas Sr. died in 1854 in Piqua, Ohio, as did his wife Applonia eleven years later. One of their sons, Nicholas Jr., also died in Piqua, while another son, Jacob, moved with his family to Knox County, Missouri, just west of Quincy, and died there in 1896.

The next landowner associated with the barn appears to be David Church, who is listed as the owner of the original Deal quarter section in an 1859 Perry County plat book (Plat Map of Perry County, 1859). Church was born in Oxford, New York, in 1793 and died in Perry County in 1869 (David Church Ancestral File). The Church family came to be linked with the Rousculp family (the barn’s current “namesake”) through marriage, as one of David and Mary Church’s daughters, Martha Irene, married Elias Rousculp in Perry County in 1865; Elias appears as the landowner of the quarter section in a plat map appearing in an 1875 atlas (Lake 1875, 11). The Rousculp family (likely originally spelled Rauschkolb) were pioneer settlers in Perry County. Elias’s father, Jacob, was born in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, in 1804 and moved with his mother and father to Perry County sometime in the 1820s, as Elias was born in Perry County in 1833. One of Elias and Martha’s sons, Albert William, was born in 1874, and it is highly likely that it was he who carved the initials “AWR” into one of the barn’s stone foundation blocks in 1896 when he was a young man of twenty-two. Another family associated with the land and the barn is the Cotterman family. A family sketch in an 1883 history of Fairfield and Perry counties (Colburn 1883) notes that Elias’s father, Jacob, purchased the “Cotterman farm” — the northwest quarter of section four in Reading Township — in 1868. The Cotterman family (likely originally spelled Katterman) was another Perry County pioneer family. Michael Cotterman was born in Berks County, Pennsylvania, in 1777 and was in Perry County by at least 1820, as his first son, Phillip, was born there in that year. The Cotterman’s also came to be linked with the Rousculp family through marriage, as Phillip’s son, Clarence, later married one of Elias and Martha Rousculp’s daughters, Mary Elizabeth (Ohio County Marriages). The land and barn remained in the Rousculp/Cotterman family well into the 20th century, as one of Clarence and Mary’s sons, Homer, and his wife Isabelle appear as the owners of the quarter section on a 1974 Perry County plat map (Plat Map of Perry County, 1974).

Situating the Barn in Time and Space

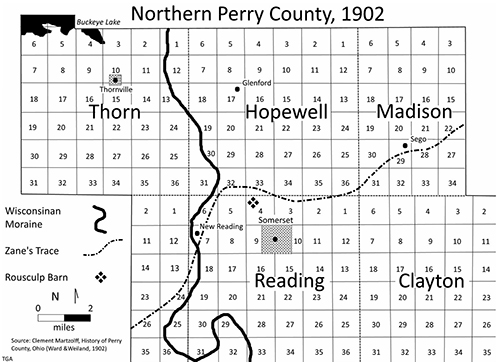

The Deal, Gangloff, Cotterman and Rousculp families were all part of a larger migration of Pennsylvania-Germans out of the group’s colonial “core” region in southeast Pennsylvania to the northern Shenandoah Valley, central Pennsylvania, southwestern Ontario and central and eastern Ohio during the early Federal era from 1790 to about 1850. This large-scale migration was driven by a variety of factors and circumstances, including rising land prices and quitrents, poor soil conservation practices and divisions of holdings over successive generations, all of which led to decreasing returns on investments in southeastern Pennsylvania (Lemon 1972, 77, 84, 86-88, 93). Data from the 1850 federal census reveal just how significant the Pennsylvania-German element was during the early, formative stage of Anglo settlement in Ohio. Of the approximately 500,000 persons not born in Ohio, about half were born in the mid-Atlantic region, and of these about forty percent were born in Pennsylvania (Wilhelm 1982, 23-25). When these census data are mapped at the county and township level it is clear that Pennsylvania-Germans accounted for over half of the non-Ohio-born population in two major areas of the state: a six-county region centered between Columbus and Cleveland, and a five-county region centered around the city of Lancaster to the south and east of Columbus, along the former route of Zane’s Trace, a principal route of ingress into the Ohio Country. This latter region is situated along the margin of the Wisconsinan glacial moraine and is underlain by rich soils developed on glacial till, allowing for the continued practice of the extensive, mixed commercial farming system that distinguished the Pennsylvania-German agricultural economy. The 1850 census recorded only state of birth, but genealogical data and information gleaned from individual family histories and biographies contained in county histories and atlases from the 1870s confirm that a majority of these early settlers hailed from Berks, Bucks, Chester, Montgomery and Dauphin counties in Pennsylvania, the core region of the Pennsylvania-German “homeland” to the north and west of Philadelphia, and had begun to migrate to Ohio as early as the 1790s. By 1850 about 6,000 Pennsylvania-born settlers resided in the Fairfield-Perry-Ross-county region centered on Lancaster. This figure represented only about eleven percent of the total population of the area, but fully half of the non-Ohio-born population (Anderson 2001, 144-149).

Because Pennsylvania-Germans were the first effective Anglo settlers in the region, many aspects of the agricultural system practiced in southeastern Pennsylvania, along with several distinctive material culture elements, were transplanted to central and eastern Ohio, leaving behind an indelible mark on the area’s cultural landscape. Certainly the most conspicuous of these elements is the Pennsylvania forebay bank barn, of which the Rousculp barn, standing just to the north and west of Somerset along the former route of Zane’s Trace, is a classic example (Figure 6). It is hardly surprising that Pennsylvania bank barns moved westward with Pennsylvania-German settlers, given that barn form is often a function of the agricultural system employed by its builders. Agricultural censuses from the 1850s reveal a continued reliance on both crops and livestock in an extensive mixed commercial farming system imported from Pennsylvania. While wheat was the primary grain crop grown in Pennsylvania, corn quickly became most dominant in Ohio. Corn was fed to cattle and hogs and did quite well on the rich glacial till covering most of central and eastern Ohio, and by 1850 the region was becoming one of the premier agricultural regions of the state as the area became linked to Midwestern and eastern markets by canals and roads. With a continued reliance on both livestock and crops, the forebay bank barn remained a part of the Pennsylvania-German farming landscape in Ohio as it served the twin purposes of hay and grain storage and of livestock stabling (Anderson 2001, 149-150).

Figure 6. Site of the Rousculp Barn in Northern Perry County. Map by Author.

Although the Rousculp barn is part of a larger “Pennsylvania extended” cultural landscape in Ohio, only one of perhaps hundreds of Pennsylvania bank barns in the state, it stands out from the crowd in a number of ways. Most significantly, the barn is one of perhaps only a small handful of such barns in Ohio whose style, form and construction method (bank barn style; Sweitzer form; double-crib log construction) is virtually identical to barns found in the southeastern Pennsylvania source region. Of the 85 extant Pennsylvania bank barns observed and recorded by the author in the Fairfield-Perry-Ross county region, the Rousculp barn is the only double-crib log Sweitzer. Moreover, the vast majority of the Pennsylvania barns in Ohio exhibit minor, and sometimes major, variances that set them apart from those in Pennsylvania, even if the basic form was repeated on those built in Ohio, including the occurrence of at least six of the eighteen variant forms of the barn identified by Ensminger (1992). First, the use of stone as foundation material is extremely rare on Ohio barns. Second, the characteristic forebay on most Ohio barns is either partially or fully enclosed, supported by timbers or walls on one or each gable end. That the Rousculp barn retains these features further sets it apart from other Pennsylvania barns in the region and in the state, and as such it remains a significant landscape signature associated with the large-scale migration of Pennsylvania-German pioneers into the Old Northwest during the early Federal period.

References

Anderson, T. G. 2001. “The Creation of an Ethnic Culture Complex Region: Pennsylvania-Germans in Central Ohio, 1790-1850.” Historical Geography 29: 135-157.

“Christian Deal Patent.” 1812. Bureau of Land Management, General Land Office Records. http://www.glorecords.blm.gov, last accessed 20 May 2015.

Colburn, E. S. 1883. History of Fairfield and Perry Counties, Ohio. Lancaster, OH: A.A. Graham.

Comeaux, M. M. 1989. “The Cajun barn.” Geographical Review 79: 47-62.

“David Church Ancestral File.” n.d. Family Search, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/2:1:M43W-9F1, last accessed 23 May 2015.

Dornbusch, C. H. and Heyl, J. D. 1958. “Pennsylvania German Barns.” The Pennsylvania German Folklore Society, Vol. 21. Allentown, PA: Schlechter’s.

Ensminger, R. F. 1992. The Pennsylvania barn: Its origin, evolution, and distribution in North America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Ensminger, R. F. 2008. Personal communication with author. Kutztown, PA, June 8.

“Gangloff/Wahl Family Group Sheet.” n.d. http://www.perrycofamililies.org, last accessed 20 May 2015.

Glass, J. W. 1986. The Pennsylvania culture region: A view from the barn. Ann Arbor: UNI Research Press.

Glassie, H. 1968. Pattern in the material folk culture of the eastern United States. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Hart, J. F. 1968. “Field patterns in Indiana.” Geographical Review 58: 450-471.

Hart, J. F. 1994. “On the classification of barns.” Material Culture 26 (3): 37-46.

Hubka, T. C. 1984. Big house, little house, back house, barn: The commercial farm buildings of New England. Hannover, NH: University Press of New England.

Jordan, T. G. 1966. “On the nature of settlement geography.” The Professional Geographer 18 (1): 26-28.

Jordan-Bychkov, T. G. 1988. ”Transverse-crib barns, the Upland South, and Pennsylvania extended.” Material Culture 30 (2): 1-31.

Kilpinen, J. T. 1994. “The mountain horse barn: A case of western innovation.” Pioneer America Society Transactions 17: 25-32.

Kniffen, F. 1965. “Folk Housing: Key to diffusion.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 55 (2): 549-577.

Lake, D. J. 1875. Atlas of Perry County, Ohio. Philadelphia: Titus, Simmons & Titus.

Lemon, J. T. 1972. The Best Poor Man’s Country: A Geographical Study of Early Southeastern Pennsylvania. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Martzolff, C. 1902. History of Perry County, Ohio. New Lexington, OH: Ward & Weiland.

Morrison, A. R. 2001. “Ethnicity and acculturation: German immigrant homes and barns of southern Indiana: The Schaffer farmstead, 1845-2000.” Material Culture 33 (3): 29-63.

Noble, A. G. 1977. “Barns as elements of the settlement landscape of Ohio.” Pioneer America 9 (1): 62-79.

Noble, A. G. and Seymour, G. A. 1982. “Distribution of barn types in the northeastern United States.” Geographical Review 72: 155-170.

Noble, A. G. and Wilhelm, G. H., eds. 1995. Barns of the Midwest. Athens: Ohio University Press.

“Ohio, County Marriages, 1789-2013.” Family Search, https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XZTZ-1T7, last accessed 23 May 2015.

“Perry County Tax Duplicate.” 1828. http://www.perrycountyohio.us/1828tax/readingly3.htm, last accessed 20 May 2015.

Pillsbury, R. 1977. “Patterns in the folk and vernacular house forms of the Pennsylvania culture region. Pioneer America 9 (1): 12-31.

“Plat Map of Perry County, Ohio.” 1846. http://www.perrycountyohio.us/1846plat.htm, last accessed on 20 May 2015.

“Plat Map of Perry County, Ohio.” 1859. http://www.perrycountyohio.us/1859plat/reading.htm, last accessed on 23 May 2015.

Plat Map of Perry County, Ohio.” 1974. http://www.perrycountyohio.us/1974plat/reading1974.jpg, last accessed 23 May 2015.

Raitz, K. 1995. “Tobacco barns and sheds.” In A. Noble and H. Wilhelm, eds., Barns of the Midwest. Athens: Ohio University Press, 125-146.

Roberts, W. E. 1993. “An early haypress and barn on the Ohio River.” Material Culture 25 (1): 29-36.

Schein, R. H. 1997. “The place of landscape: A conceptual framework for interpreting the American scene.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 87 (4): 660-680.

Sculle, K. A. and Price, H. W. 1993. “The traditional barns of Hardin County, Illinois.” Material Culture 25 (1): 1-27.

Stone, K. H. 1965. “The development of a focus for the geography of settlement.” Economic Geography 41 (4): 346-355.

“United States Census, 1850.” Family Search, https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MXQT-X88, last accessed 21 May 2015.

“United States Index to Passenger Arrivals, Atlantic and Gulf Ports, 1820-1874.” n.d. Family Search, https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:KD5K-5NB, last accessed 23 May 2015.

Wilhelm, H. G. 1982. The Origin and Distribution of Settlement Groups: Ohio, 1850. Athens, OH: Cutler Printing.

Zelinsky, W. 1958. “The New England connecting barn.” Geographical Review 48: 540-553.

Contributor Biography

Timothy Anderson is Associate Professor in the Department of Geography at Ohio University where he teaches courses in human geography. His research interests include the historical settlement geography of the United States, especially with regard to the historical production of regional cultural landscapes and identities, the historical settlement geography of Ohio during the early National period, with an emphasis on sub-regional cultural landscape formation, and the production of cultural landscapes associated with Germanic diasporas in North America and Europe.

Return to top